Greenland sharks: Toxic, half-blind giants of the ocean

Greenland sharks live longer than any other vertebrate.

Greenland sharks (Somniosus microcephalus) are the longest-living animals with a backbone, and survive for up to hundreds of years in the deep, cold waters of the Arctic and North Atlantic oceans. Greenland sharks belong to a family called sleeper sharks, which move slowly and stealthily through the water.

These sharks sneak up on live prey and scavenge a variety of dead animals, including other sharks, seals, drowned horses and polar bears. Greenland sharks rarely encounter humans and scientists still have much to learn about their lifestyles.

How big are Greenland sharks?

Greenland sharks grow up to 24 feet (7.3 meters) long and weigh up to 2,645 pounds (1,200 kilograms), according to the St. Lawrence Shark Observatory (ORS). That's longer than great white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias), which are estimated to grow up to 20 feet (6 m) long. (Although unconfirmed reports suggest they can reach 23 feet (7 m) in length, according to the Florida Museum of Natural History.)

Size: Up to 24 feet (7.3 m)

Life span: 272 years (estimate)

Conservation status: Vulnerable

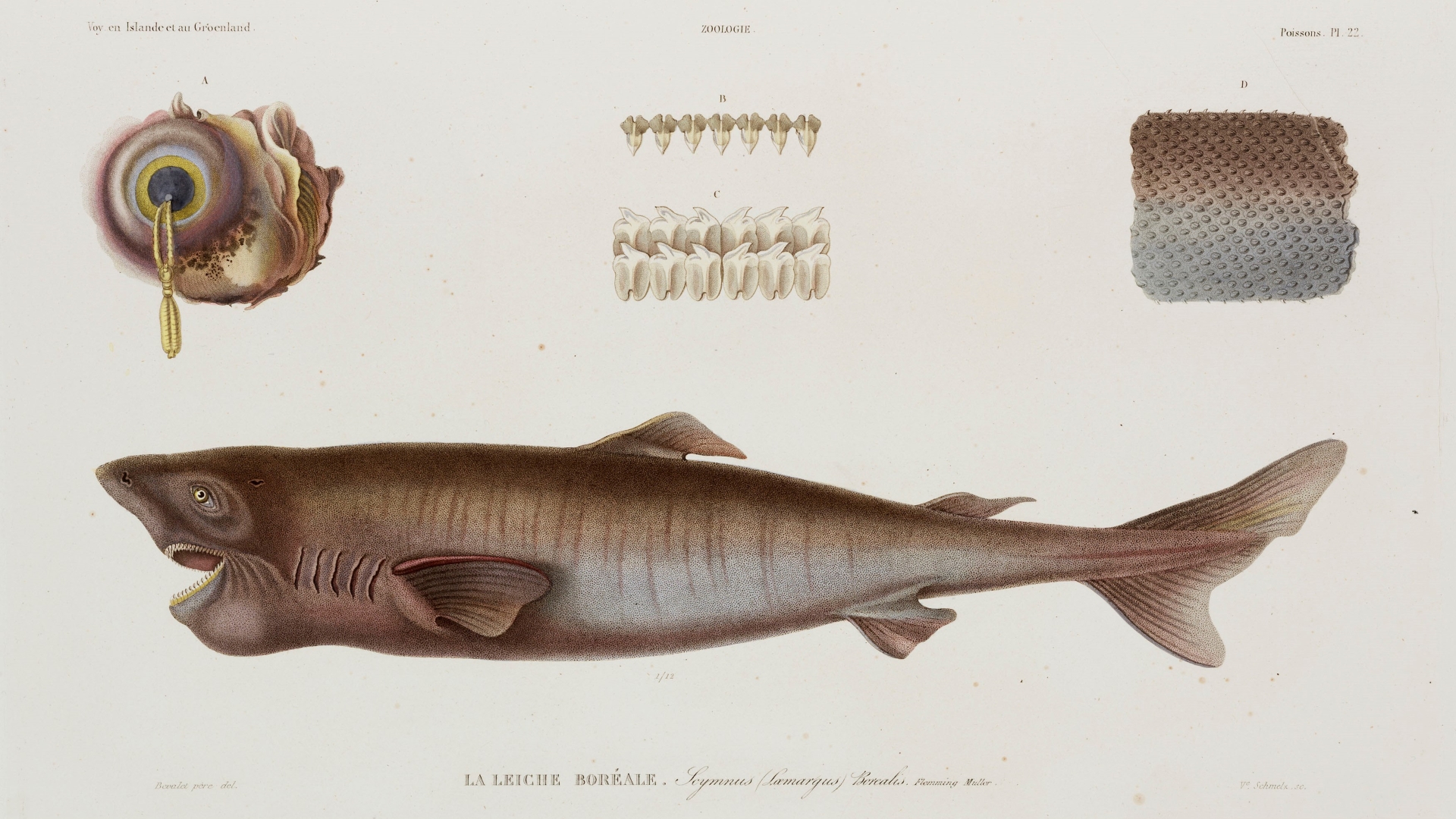

Greenland sharks have cylindrical bodies covered in teeth-like scales, called dermal denticles. These specialized scales reduce drag and help the sharks move more silently through the water, according to the ORS. The sharks can be black, brown, gray or a mixture of all three colors, and they may have spots.

A Greenland shark's mouth contains 48 to 52 teeth in its upper jaw and 50 to 52 teeth in its lower jaw. The upper teeth are pointed, to help the sharks hold on to larger food, while the lower teeth are wide and curved sideways so the sharks can carve out round chunks of flesh from prey by moving their head in a circular motion, according to the ORS.

Are Greenland sharks blind?

Ocean parasites called Ommatokoita elongata can render Greenland sharks partially blind. Ommatokoita elongata attach themselves to the eyes of Greenland sharks and can grow up to 1 inch (2.5 centimetres) long, according to the Encyclopedia of Life. The eye parasite tends to live in just one of the shark's eyes so they usually don't go completely blind. Because the sharks rely more on their other senses to catch prey in the dark ocean waters, the parasites don't seem to affect the sharks much, according to the Florida Museum of Natural History.

Related: Ancient Greenland shark reveals its age in eerie underwater video

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

How long do Greenland sharks live?

Greenland sharks' exact life span is unknown. A 2016 study published in the journal Science estimated that Greenland sharks have a maximum life span of at least 272 years, based on analysis of the sharks' eye tissue. Researchers estimated that the oldest Greenland shark in that study was about 392 years old, but the estimate had a margin of error of 120 years, which led to speculation that Greenland sharks could live to 512 years old. The estimated range hasn't been verified.

"It's important to keep in mind there's some uncertainty with this estimate," Julius Nielsen, co-author of the 2016 paper, previously told Live Science. "But even the lowest part of the age range — at least 272 years — still makes Greenland sharks the longest-living vertebrate known to science."

Greenland sharks live in the slow lane, with a top swimming speed of less than 1.8 mph (2.9 km/h). They also grow slowly at less than 0.4 inch (1 centimeter) per year and have slow metabolisms, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Scientists don't yet know how Greenland sharks live so long, but it may be linked to their slow way of life.

Related: No, scientists haven't found a 512-year-old Greenland shark

Where do Greenland sharks live?

Greenland sharks live in the Arctic and North Atlantic oceans from North America to Greenland and from Portugal to the East Siberian Sea, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The sharks have a large range and can be found swimming from the surface down to depths of 8,684 feet (2,647 m), the IUCN says.

Scientists still have much to learn about how Greenland sharks live and reproduce. Female Greenland sharks give birth to live young, called pups, that hatch from soft eggs that females carry inside their bodies. In a 2020 study published in the journal PLOS One, researchers estimated that Greenland sharks can give birth to between 200 and 324 pups per pregnancy, depending on the size of the shark. Greenland shark pups are just 14 to 18 inches (35 to 45 centimeters) long when they're born. However, little is known about how Greenland shark pups spend their early lives or how many survive to adulthood.

What do Greenland sharks eat?

Greenland sharks have a varied diet that includes fish, other sharks, eels and marine mammals, such as seals. They have also been found with drowned land animals, including horses and reindeer, in their stomachs, and have been seen in large numbers at the sea surface, feeding together on the remains of whales and fish killed by commercial whaling and fishing, according to the University of Michigan's Animal Diversity Web (ADW).

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Chondrichthyes

Order: Squaliformes

Family: Somniosidae

Genus and species: Somniosus microcephalus

Source: ITIS

Scientists have even found a Greenland shark with the jaw of a young polar bear (Ursus maritimus) in its stomach, Reuters reported in 2008. The researchers were unsure how it got there; but most shark experts believed that the polar bear was likely already dead when the shark ate it, as live polar bears are too dangerous for the sharks to take on. Researchers also found some polar bear muscle tissue and skin in the stomach of another Greenland shark during a 2014 study published in the journal Polar Biology, and they concluded that the bear was likely scavenged rather than hunted.

Does anything eat Greenland sharks?

Greenland sharks are near the top of the food chain, but sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus) may hunt them. Chris Harvey-Clark, co-founder of the Greenland Shark and Elasmobranch Education and Research Group (GEERG, now the ORS), wrote in Capeia, an online science communication magazine, about recording a Greenland shark seemingly fleeing from the echolocation clicks of a foraging sperm whale.

Upon its death, that same echolocating sperm whale was found with its teeth worn down to stumps, similar to those of orcas (Orcinus orca) that feed on Pacific sleeper sharks (Somniosus pacificus). Greenland sharks are closely related to Pacific sleeper sharks and have similarly tough skin. To explain the sperm whale tooth wear and a fleeing Greenland shark, Harvey-Clark theorized that the sperm whale hunted Greenland sharks. Scientists have yet to observe sperm whales hunting these sharks elsewhere.

Related: Sperm whales outwitted 19th-century whalers by sharing evasive tactics

Are Greenland sharks dangerous?

There are no verified reports of Greenland shark attacks on humans. However, some anecdotal evidence suggests that such attacks could occur. GEERG divers observed a Greenland shark "stalk" a team of divers. They have also seen Greenland sharks investigate diver activities as if they were scouting seal prey, according to the ORS. A Greenland shark was reportedly found with a human leg in its stomach off Canada's Baffin Island around 1859, but this report was not verified.

Is Greenland shark meat toxic?

Untreated Greenland shark meat is toxic to humans. Their meat contains high levels of trimethylamine oxide (TMAO), which breaks down into the poisonous trimethylamine (TMA) compound during digestion, according to a 1991 study published in the journal Toxicon. TMA can cause severe intestinal problems and produces similar effects to excessive alcohol consumption.

Greenland shark meat is edible only when dried. The dried meat is fed to sled dogs in northern regions such as Greenland, according to the Florida Museum of Natural History. The meat is also fermented and consumed by people inIceland, where the food, called Hákarl, is considered a delicacy.

Are Greenland sharks endangered?

The IUCN considers Greenland sharks to be vulnerable to extinction. Humans killed Greenland sharks for their liver oil to use in lamps and other products between the 13th and 20th centuries. The commercial fishing of Greenland sharks for their oil ended by the 1960s, which helped their population rebound. However, Greenland sharks continue to be caught and killed as bycatch, or animals that get pulled up by fishers alongside their intended catch, for example, in large nets dragged along the bottom of the ocean intended to catch a large number of fish. Most of the Greenland sharks eaten by humans and fed to dogs come from bycatch, although some sharks are targeted on a small scale.

The Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization (NAFO), an intergovernmental fishing science and management body, prohibits the direct fishing of Greenland sharks and seeks to reduce bycatch. The NAFO applies to most fisheries in the northwest Atlantic Ocean and includes countries such as the U.S. and Canada. But thee IUCN recommends the development and enforcement of further protections, such as bycatch policy, for Greenland sharks.

The IUCN estimates that the Greenland shark population has declined by 30% to 49% over the past 450 years, or three shark generations. However, this decline was estimated based on a conservative Greenland shark life span of 150 years; the decline could be much higher if the sharks have longer life spans and thus take longer to reach reproductive age and produce more sharks. The global Greenland shark population size is unknown. Climate change is also hurting the species — for example, by reducing Arctic sea ice, which gives fishing fleets easier access to Greenland shark habitat.

Additional resources

Visit the Encyclopedia of Life website for more information about where these sharks live. The website provides an interactive map of Greenland shark observations around the world. You can see more photos and videos of Greenland sharks and other deep sea creatures on the NOAA Ocean Exploration website. Preparing Greenland shark meat for human consumption is a long process that we don't delve into on this page. To find out more about the process, you can watch this short video on YouTube from Food Insider.

There aren't reliable books on Greenland sharks specifically, but for a general guide to the world's sharks, check out "Sharks of the World: A Complete Guide" (Princeton University Press, 2021).

Bibliography

- Alister Doyle, Reuters, "Polar bear eaten by shark: who's top predator?" Aug. 11, 2008. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-arctic/polar-bear-eaten-by-shark-whos-top-predator-idUSLB66891920080811

- Anthoni et al. "Poisonings from flesh of the Greenland shark Somniosus microcephalus may be due to trimethylamine," Toxicon, Volume 29, 1991. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1801314/

- Chris Harvey-Clark, Capeia, "Unknown Monster, Dreamless Sleeper: the Greenland Shark II," Aug. 12, 2017. https://beta.capeia.com/zoology/2017/06/14/unknown-monster-dreamless-sleeper-the-greenland-shark-ii

- Encyclopedia of Life, "Ommatokoita elongata." https://eol.org/pages/1037051

- Florida Museum of Natural History, "Carcharodon carcharias," Oct. 18, 2018. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/carcharodon-carcharias/

- Florida Museum of Natural History, "Somniosus microcephalus," Dec. 5, 2019. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/somniosus-microcephalus/

- Kulka et al. "Somniosus microcephalus, The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species," 2020. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/60213/124452872

- Mills, P, Animal Diversity Web, "Somniosus microcephalus," 2006. https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Somniosus_microcephalus/

- Mindy Weisberger, Live Science, "Greenland Sharks May Live 400 Years," Dec. 15, 2017. https://www.livescience.com/55736-greenland-sharks-longest-lived-vertebrates.html

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), "How long do Greenland sharks live?" March 1, 2021. https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/greenland-shark.html

- Nielsen et al. "Assessing the reproductive biology of the Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus)," PLOS One, Volume 15, Oct. 7, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238986

- Nielsen et al. "Distribution and feeding ecology of the Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus) in Greenland waters," Polar Biology, Volume 37, Oct. 10, 2013. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00300-013-1408-3

- Nielsen et al. "Eye lens radiocarbon reveals centuries of longevity in the Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus)," Science, Volume 353, Aug. 12, 2016. https://www.science.org/doi/abs/10.1126/science.aaf1703

- St. Lawrence Shark Observatory (ORS), "Meet the world's oldest-living vertebrate, the Greenland Shark," 2019. https://geerg.ca/en/greenland-shark/

Patrick Pester is the trending news writer at Live Science. His work has appeared on other science websites, such as BBC Science Focus and Scientific American. Patrick retrained as a journalist after spending his early career working in zoos and wildlife conservation. He was awarded the Master's Excellence Scholarship to study at Cardiff University where he completed a master's degree in international journalism. He also has a second master's degree in biodiversity, evolution and conservation in action from Middlesex University London. When he isn't writing news, Patrick investigates the sale of human remains.