Hashimoto's disease: Causes, symptoms and treatment

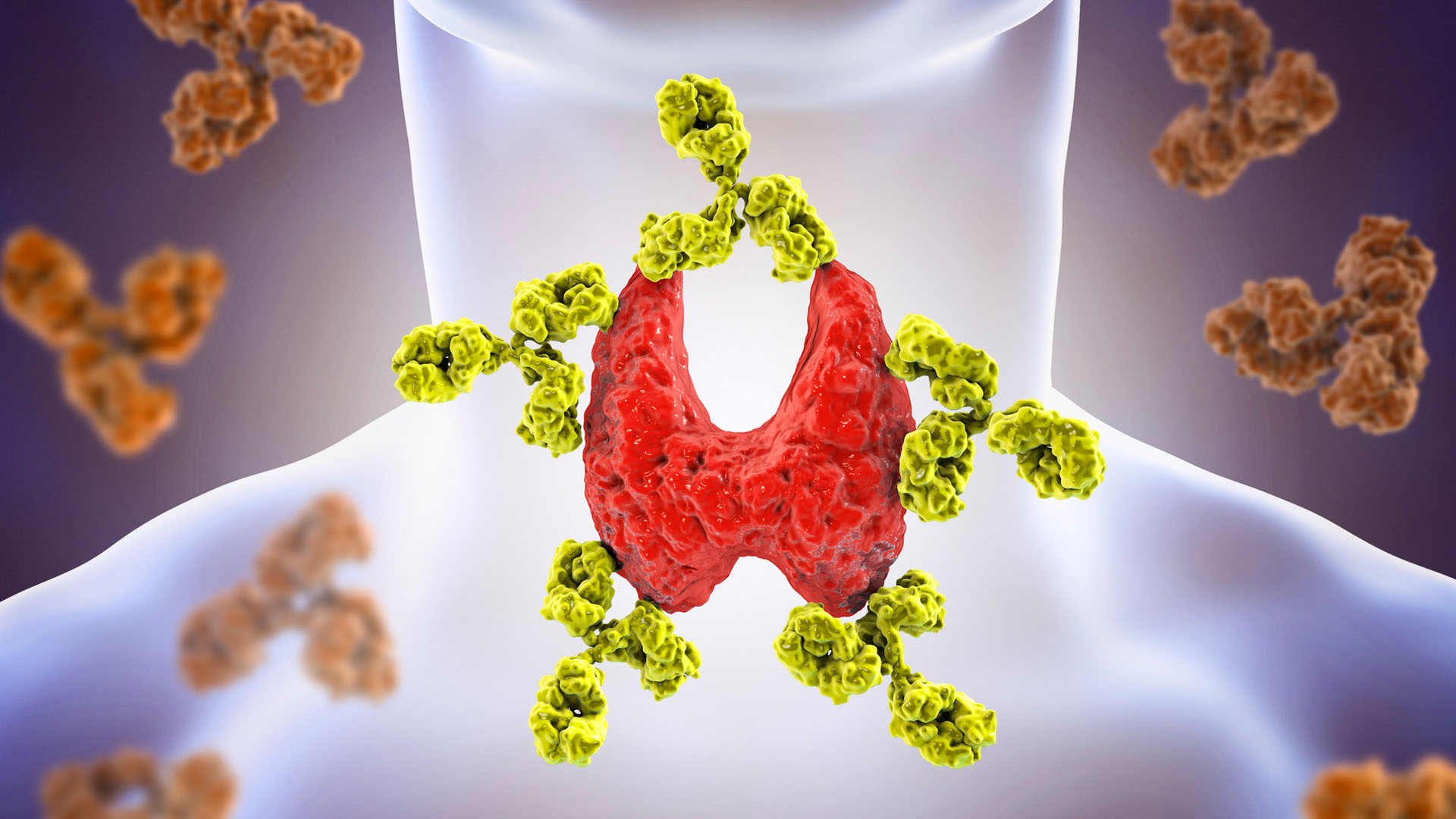

Hashimoto's disease, or Hashimoto thyroiditis, is an autoimmune condition affecting the thyroid gland.

Hashimoto thyroiditis — also known as Hashimoto's disease or chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis — is an autoimmune condition, meaning antibodies from a person's own immune system attack a part of the body. In the case of Hashimoto's, the target of the antibodies is the thyroid gland.

The thyroid is a butterfly-shaped gland in the neck that controls metabolism. Unlike in Graves disease, in which antibodies stimulate the thyroid to overproduce thyroid hormones (a condition known as hyperthyroidism), Hashimoto's disease starts with a short period of hyperthyroidism and ends with low thyroid function. This is known as hypothyroidism, or an underactive thyroid.

The number of people who have Hashimoto’s disease in the United States is unknown, according to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), but it is the most common cause of hypothyroidism which affects about 5 in 100 Americans. However, while Hashimoto’s disease is the most common cause of hypothyroidism, a person can be hypothyroid without a Hashimoto’s etiology.

What causes Hashimoto's disease?

The nature of the immune attack on the thyroid explains why Hashimoto's can begin with hyperthyroidism and end with hypothyroidism. Thyroid cells contain the hormones triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4), which are waiting to be released into the blood as needed. When Hashimoto antibodies — such as thyroid peroxidase (TPO), thyroglobulin (TG), and thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin (TSI) — strike the thyroid, however, a couple of things happen. If TSI is among the antibodies striking the thyroid, thyroid cells are stimulated to release their hormones. Whether or not TSI is among the antibodies striking the thyroid, other antibodies, such as TPO damage thyroid tissue, causing the hormones (T3 and T4) to leak into the blood fairly rapidly. The damage is generally permanent, so, ultimately, the thyroid cells will not be able to produce more hormones.

Meanwhile, high levels of thyroid hormones have been released, so, over a period of several days, levels of T3 and T4 in the blood rise. This causes hyperthyroidism (high concentrations of thyroid hormones) that typically lasts up to two weeks. However, because the gland is damaged, it cannot produce more hormones. After this brief spike, the amounts of T3 and T4 in the blood begin dropping. The person goes through a period of having normal levels of thyroid hormones in the blood (this is called being euthyroid).

Because the hyperthyroid period is so brief and because the person then goes through a euthyroid state on the way to becoming hypothyroid, temporary hyperthyroid symptoms are not always noticed. The thyroid hormone levels then keep dropping, so the person becomes increasingly hypothyroid and remains that way.

It isn't clear what causes the immune system to attack thyroid cells, according to the Mayo Clinic. Genetic factors, environmental triggers (such as an infection or stress) or a combination of the two may play a role.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Hashimoto's risk factors

Hashimoto's disease is four to 10 times more common in women than in men, according to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). It often develops between the ages of 30 and 50.

Having a first-degree relative with Hashimoto's puts a person at an increased risk for the condition, according to the NIDDK. Other risk factors include having other autoimmune conditions, such as celiac disease, rheumatoid arthritis or type 1 diabetes.

What are the symptoms of Hashimoto's disease?

According to the National Institute of Health (NIH), symptoms of Hashimoto's disease include:

- Sluggishness and fatigue

- Weight gain

- Constipation

- Muscle weakness

- Muscle aches and stiffness

- Joint pain and stiffness

- Dry, pale skin

- Puffy face

- Hair loss

- Brittle nails

Additionally, people may have an enlarged tongue, feel depressed, have memory difficulty, and feel too cold. Women may have prolonged or excessive menstrual bleeding.

However, a few weeks prior to the hypothyroid symptoms, people may experience symptoms of hyperthyroidism. Such symptoms include palpitations (feeling like the heart is racing, pounding or skipping beats), nervousness, increased appetite, gastrointestinal disturbances, feeling too hot, fatigue or muscle weakness, and insomnia. The thyroid also may be enlarged or tender, according to the American Thyroid Foundation, but only for the initial hyperthyroidism phase.

How is Hashimoto's disease diagnosed?

Diagnosis for Hashimoto's begins with a blood test to measure the amount of a hormone called thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) in the blood. TSH is a hormone that comes from the pituitary gland at the base of the brain. In Hashimoto’s disease, once a person has reached the hypothyroid phase, TSH is elevated in the blood while thyroid hormone, specifically T4, is too low.

Additionally, doctors test the blood for antibodies against an enzyme called thyroid peroxidase. The test for this antibody is not specific for Hashimoto's, meaning that many people test positive for the antibodies without experiencing symptoms, or when they have another condition, such as Graves disease. Thus, doctors must interpret the test results in the context of a person's symptoms and signs that come up upon physical examination.

Complications of Hashimoto's disease

If left untreated, Hashimoto's disease can deteriorate into an extreme form of hypothyroidism called myxedema, according to an article in the journal American Family Physician. This condition is characterized by an abnormally low body temperature, decreased function of multiple organs, and decreasing mental status, until the person enters a coma.

Thyroid function in pregnancy

Pregnancy can lead to changes in thyroid function in multiple, complex ways. Notably, rising levels of the hormones beta human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hCG) and estrogen stimulate the release of thyroid hormones T3 and T4, causing TSH levels to drop accordingly.

However, the need for thyroid hormones also rises, particularly during the embryonic and early fetal periods, corresponding with the first trimester. This is because the baby cannot produce its own thyroid hormones adequately until the second trimester. Consequently, the phenomenon of beta-hCG and estrogen stimulating the thyroid, causing higher than normal T3/T4 levels, is counterbalanced by the increased need for the thyroid hormones. The balance can be different in different women, leading in some cases to relative hypothyroidism, meaning that thyroid activity is not enough to keep up with needs.

On top of this, growth of the fetus and changing hormonal situations further increase the need for thyroid hormones as pregnancy advances into the second trimester. Because relative hypothyroidism is associated with an increased risk of miscarriage, it is recommended TSH levels are monitored and maintained throughout pregnancy, according to the American Thyroid Association. Maintaining TSH levels means taking thyroid hormone therapy (levothyroxine) when TSH levels get too high (meaning thyroid hormones are too low) and stopping levothyroxine when TSH levels get too low (meaning thyroid levels are too high).

At the same time, having low thyroid function before or during pregnancy can lead to complications. In this case, the embryo or fetus is at elevated risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, small size for gestational age, and intrauterine fetal death.

Hashimoto's disease can occur before, during or after pregnancy. When it occurs just after delivery, however, it must be distinguished from another phenomenon, called postpartum thyroiditis. In this instance, thyroid function usually returns to normal after several months, though not always.

How is Hashimoto's disease treated?

Hashimoto's disease is typically diagnosed after the initial, hyperthyroid phase. If someone experiences a hyperthyroid episode, however, it may be treated with a type of medication called beta-blockers, which slow heart rate.

Once someone becomes hypothyroid, they need to take a synthetic thyroid hormone, levothyroxine (L-T4), every day. They are likely to need this treatment throughout their life.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

David Warmflash is a medical researcher, astrobiologist, science communicator, and author, located in Portland, Oregon. He holds an MD from Tel Aviv University Sackler School of Medicine and has conducted research in astrobiology, space biology, and space medicine during research fellowships at NASA's Johnson Space Center, the University of Pennsylvania, and Brandeis University, and in collaboration with The Planetary Society and the Israeli Aerospace Medicine Institute.