Snow blankets Hawaii volcanoes in stunning satellite image

It's the second-largest area of snow cover since current records began.

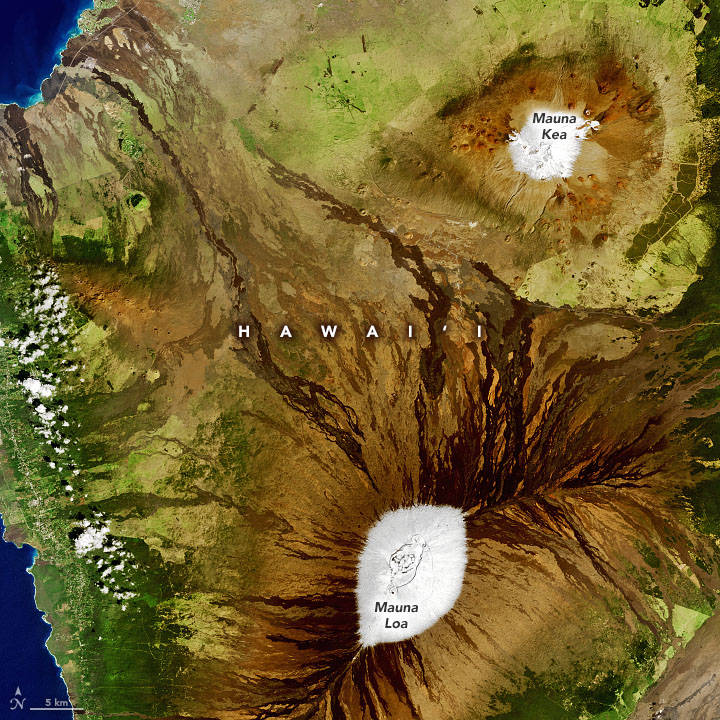

A new satellite image has captured the stunning white peaks of two volcanoes on the Big Island in Hawaii, which have experienced their second-most extensive snow coverage since current records began.

The high-resolution image — snapped on Feb. 6 by the Operational Land Imager (OLI) onboard the Landsat-8 satellite — shows the striking contrast between the snow-covered peaks of Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa and the surrounding volcanic rock.

The OLI, is a joint venture between NASA and the U.S. Geological Survey, and the new image was recently released by NASA's Earth Observatory.

Snow and Hawaii may seem like an oxymoron, but the frozen precipitation falls in Hawaii quite a lot. The volcanic peaks of the dormant Mauna Kea and active Mauna Loa — both over 13,600 feet (4,200 meters) above sea leve, with Mauna Kea being taller by just 125 feet (38 m) — receive at least a light dusting every year, according to NASA’s Earth Observatory.

This year, heavy storms have blanketed the peaks in snow three times in the last three weeks, beginning Jan. 18, resulting in their second-biggest covering of snow since record keeping began in 2000. Haleakalā, an active volcano on the island of Maui which has not erupted for around 400 years, which stands at 10,000 feet (3,000 m), also received a rare covering of snow on Feb. 3, which has since melted away.

Related: Big blasts: History's 10 most destructive volcanoes

Residents of the Big Island have enjoyed the snow by swapping out their surfboards for snowboards to do some carving on what they refer to as "pineapple powder" before it disappears, according to Weatherboy.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Snow in Hawaii also means that every U.S. state, except Florida, has now seen snowfall this winter, according to The Weather Channel.

Changing winds

Snow in Hawaii occurs as the result of a significant change in wind direction from a localized weather phenomenon known as a "Kona low," a Polynesian term that translates to "leeward storm."

During this phenomenon, cyclones caused by low-pressure systems to the north of the islands reverse the usual northeastern trade winds to a southwestern direction. This draws up water from the Pacific Ocean into storm clouds which get pushed over the islands. Cold air is also pushed across the islands which lowers the temperature at the peaks below freezing and causes snow to fall; that precipitation falls as rain across the rest of the island.

Kona lows can also occur in the summer months, meaning it can snow in Hawaii during the summer, too, according to AccuWeather.

In addition to capturing beautiful images of the snow, satellites also measure it. NASA's Terra satellite has been calculating the Normalized Difference Snow Index (NDSI) — the most accurate measurement for snow coverage that can currently be achieved — on the Big Island since 2000. The NDSI uses measurements of both visible light and shortwave infrared to differentiate snow from clouds, which can appear identical from space, according to National Snow & Ice Data Center.

The NDSI for Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa usually reaches its peak in the first week of February. This year, it was the highest NDSI since 2014 and the second-highest in the 21-year record.

However, the days of regular Hawaii snowfall may be numbered.

A 2017 study led by the International Pacific Research Center (IPRC) at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, using satellite data and computer models, predicted that snowfall on the volcanoes is likely to diminish throughout the rest of the century due to rising temperatures caused by climate change.

"Unfortunately, the projections suggest that future average winter snowfall will be ten times less than present-day amounts, virtually erasing all snow cover," lead author Chunxi Zhang, a meteorologist at IPRC, said in a statement at the time.

Originally published on Live Science.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.