13 proteins tied to brain aging seem to spike at ages 57, 70 and 78

A new study claims to have identified 13 proteins associated with either accelerated or decelerated brain aging. However, experts have questioned the practical implications of the findings.

Scientists have identified 13 proteins that may be linked to brain aging and could one day be targeted with anti-aging treatments.

However, experts say that more research is needed to know exactly why these proteins are tied to brain aging, and whether they point to specific solutions for diseases like dementia.

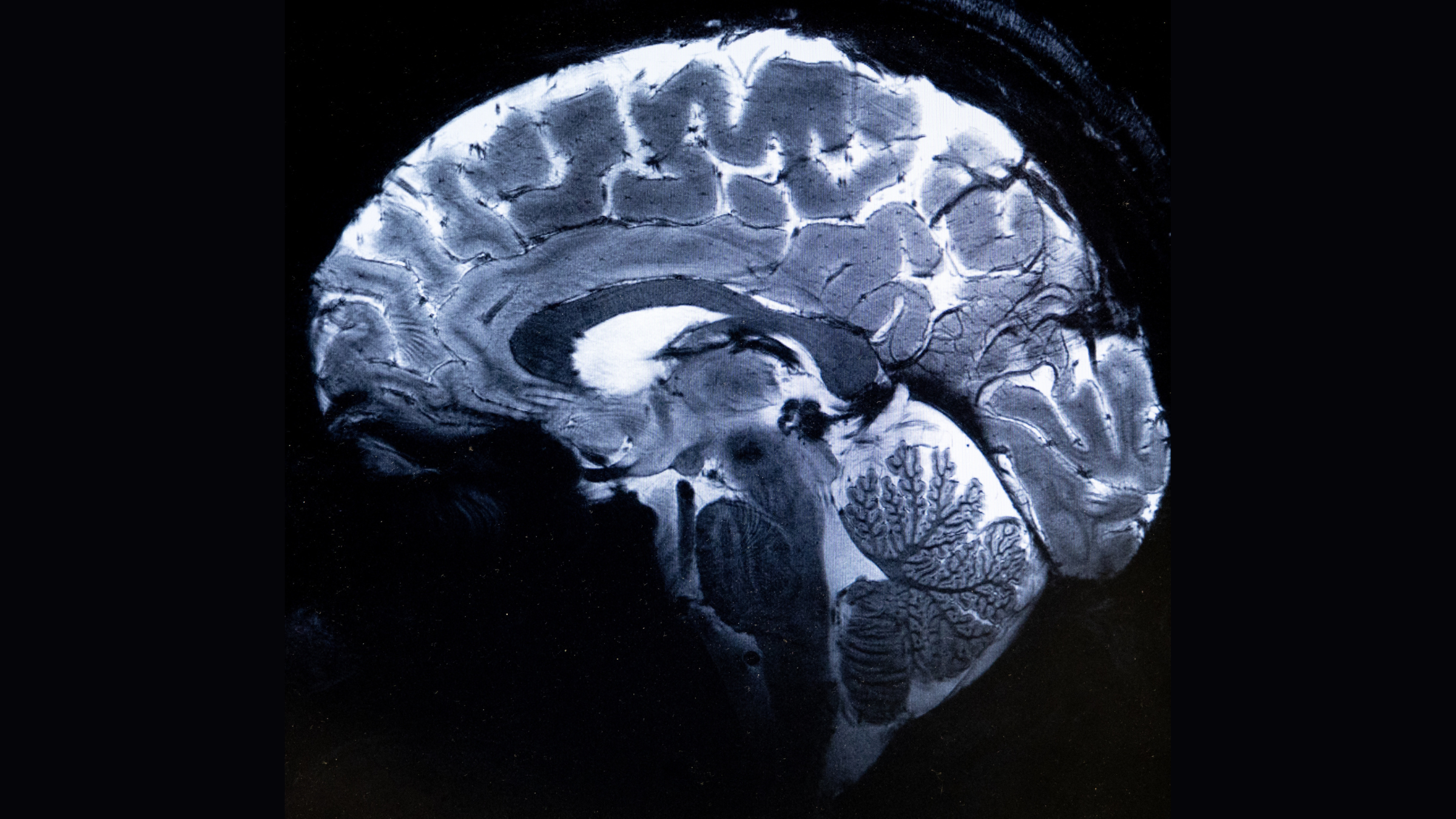

In a new study, scientists analyzed magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain scans from nearly 11,000 people ages 45 to 82. They used the scans to estimate each participant's "brain age gap" — essentially how much their "brain age" differs from their chronological age.

The team determined people's brain ages using artificial intelligence to look at specific physiological features, such as brain volume and surface area. This revealed the extent to which their brains were undergoing accelerated aging.

Related: Single molecule reverses signs of aging in muscles and brains, mouse study reveals

The team then assessed the concentration of approximately 3,000 proteins in the blood of nearly 5,000 of the participants. The blood connects the brain to the rest of the body, so changes in the concentration of proteins within the blood should reflect similar alterations in the brain.

Across the board, the researchers identified 13 proteins whose blood concentrations were significantly associated with biological brain age. Proteins that were linked to factors involved in aging — such as cellular stress and inflammation — increased in the blood as biological brain age rose. Meanwhile, levels of proteins that help maintain the brain's function, including those involved in cellular regeneration, decreased as people aged.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Of the proteins that the team identified, one known as brevican showed one of the strongest links with biological brain age — it decreased in concentration as people aged, and those falling numbers showed a strong correlation with conditions such as dementia and stroke.

Brevican is known to help neurons communicate with one another, so this finding supports previous research that suggested the protein could act as a measurable marker for the development of neurodegenerative diseases.

Furthermore, the scientists found that the concentrations of the 13 proteins peaked in the blood at specific chronological ages: 57, 70 and 78. This might reflect "waves" of brain aging that could be used as a reference point to target future anti-aging interventions, the team wrote in a paper published Monday (Dec. 9) in the journal Nature Aging.

However, other experts have voiced concerns about rushing to such conclusions.

The "brain waves" findings are not only "unexpected" but "go against pretty much everything that is known about brain aging," during which there is a continuous, gradual decline in brain function and associated changes in cells, Mark Mattson, an adjunct professor of neuroscience at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine who was not involved in the research, told Live Science in an email.

Many questions about the study also remain.

"The correlation between several proteins in blood samples and an MRI image-based indicator of brain aging are interesting," Mattson said. "However, the implications for using measurements of blood levels of those proteins to diagnose brain dysfunction or for developing specific interventions are unclear."

The team acknowledged several limitations of the study in their paper. For instance, they only used data from older people who were mainly of European descent, because their data was drawn from the U.K. Biobank database. More research is needed to see if the proteins fluctuate in the same ways in individuals of different races and ethnicities, as well as how they may change across the entire human life span.

It is also still unknown where in the brain these 13 proteins come from, Mattson added. "Until levels of those proteins in the brain are established, it will be unclear whether they actually play a role in brain aging," he said.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30. (emily.cooke@futurenet.com)