How many cells are in the human body? New study provides an answer.

A new analysis of more than 1,500 papers and 60 types of tissue has revealed the total number of cells in the human body.

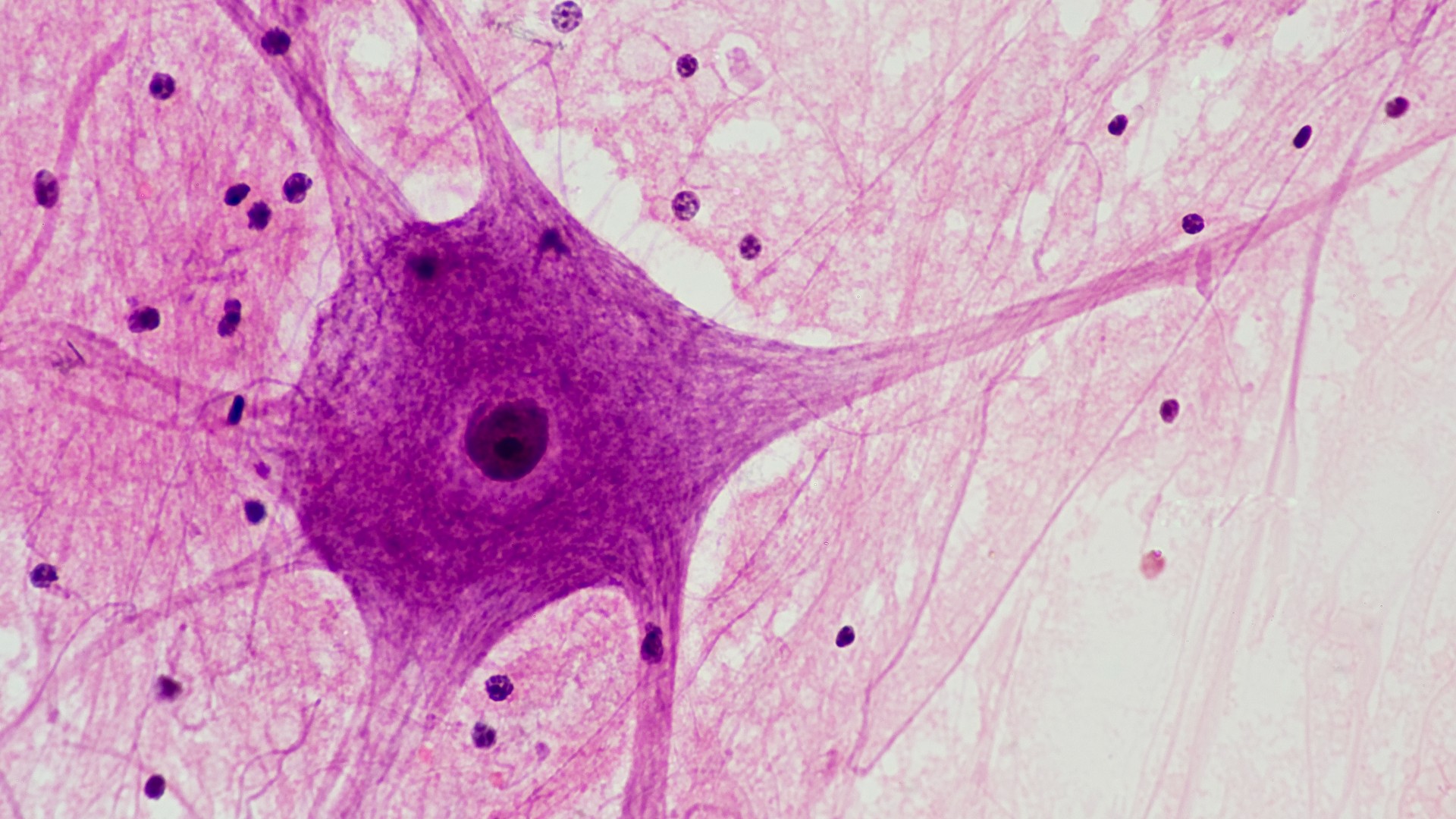

Cells are the building blocks that form all the tissues and organs of the body — and now, scientists have an estimate of just how many individual cells the human body contains.

According to a new analysis of more than 1,500 papers, the average adult male human has around 36 trillion cells — that's 36 followed by 12 zeros — while adult females have 28 trillion and 10-year-old children have about 17 trillion. To arrive at these estimates, the authors of the new study, which was published Monday (Sept. 18) in the journal PNAS, considered the size and number of 400 types of cells in the body across 60 tissues, including muscle, nerve and immune cells.

Although scientists have estimated a similar number of cells — between 30 and 37 trillion — in adult male humans before, until now, the relationship between cell size and number hadn't been studied across the whole body, according to the authors.

"We were surprised to see a fairly regular inverse relation between the size and count of cells across the whole human body," Ian Hatton, lead study author from the Max Planck Institute for Mathematics in the Sciences in Leipzig, Germany told Live Science in an email. In other words, there is a "trade-off" between cell size and number, so the larger the cell, the lower their overall number relative to smaller cells. That means, if cells are grouped by size, each group contributes the same amount to the overall mass of the body.

Related: Does the human body replace itself every 7 years?

"This pattern spans seven orders of magnitude in cell size, from the tiny red blood cells to the largest muscle cells, comparable to the mass ratio of a shrew to a blue whale," Hatton said.

The authors acknowledged several limitations of the study. For example, they focused on "average" adults' and children's bodies. Their benchmark adult male weighs 154 pounds (70 kilograms), the adult female weighs 132 pounds (60 kg) and the child weighs 70 pounds (32 kg), based on reference figures from the International Commission on Radiological Protection. This notably doesn't reflect the huge variation in size and weight that exists between humans.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"There is of course large variation between different anatomical models," Hatton said. "But other than the variation in fat and muscle content in the adipocytes [fat cells] and myocytes [muscle cells], much of the variation is probably not significant relative to the other sources of error that is associated with trying to put bounds on the many trillions of cells in the human body," he said.

Indeed, the study authors explained that there may be a lot of uncertainty in their figures. In many cases, they had to rely on inferences about the dimensions of cells made using microscopy and other indirect measurements, rather than direct measurements of the mass of different cell types. They also estimated total cell numbers for adult females and children using papers that mainly considered adult males, study author Eric Galbraith, a professor and group leader at McGill University in Canada, told New Scientist.

"There's unfortunately still more information for reference males than females or children," he told New Scientist.

Further research is needed to fill these gaps, but for now, Hatton told Live Science that the study highlighted several discrepancies in cell counts proposed in prior work, which could have potential health implications.

"Possibly most critical is our estimate of the total number of human lymphocytes, which are vital for our immune function," he said. "We estimate 2 trillion lymphocytes in the human body which is four times higher than prior estimates and could prove important in lymphocyte-related health and disease, such as HIV or leukemia." HIV and AIDS weaken the immune system by destroying certain lymphocytes, while leukemia is a cancer that affects the immune cells.

Data from the new study can be freely accessed online.

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30. (emily.cooke@futurenet.com)