Scientists just made mice 'see-through' using food dye — and humans are next

A common food dye can turn the skin of living mice transparent, but we don't yet know if it'll work in humans.

A common food dye can turn the skin of living mice transparent, enabling researchers to peer inside the body without surgery.

This is the first time scientists have used the technique to visualize the tissues of living mice under the microscope. They used a food-safe dye, which can likely be found in snacks in your pantry, and several fundamental physics principles to render the mice see-through.

Biological tissue is chock full of stuff, from proteins to fats and liquids, and each substance differs in its ability to bend, or refract, light that hits it. This property is referred to as a material's refractive index.

If light particles hit a boundary between two materials with different refractive indices, those particles are forced to change direction, or scatter. While light can easily pass straight through transparent materials — like a glass of water — opaque materials get in the light's way, sending it bouncing in many directions. That light then bounces to your eyeballs when you look at the material, and thus, the brain interprets that scattered light as coming from an opaque object. That's why you normally can't see through someone's body.

Related: Scientists breed most human-like mice yet

But now, scientists have discovered a simple trick to change the skin's transparency: They took a concentrated food dye that is great at absorbing light, dissolved it in water and then applied the solution to the skin, which balanced out the refractive indices of substances within that tissue, making it temporarily translucent.

The researchers described this approach in a new study, published Thursday (Sept. 5) in the journal Science. They tested the technique on rodents using a U.S. Food and Drug Administration-certified color additive called tartrazine, also known as FD&C Yellow No. 5. This yellow-orange dye is often added to foods such as desserts and candy, as well as various drinks, drugs and cosmetics.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

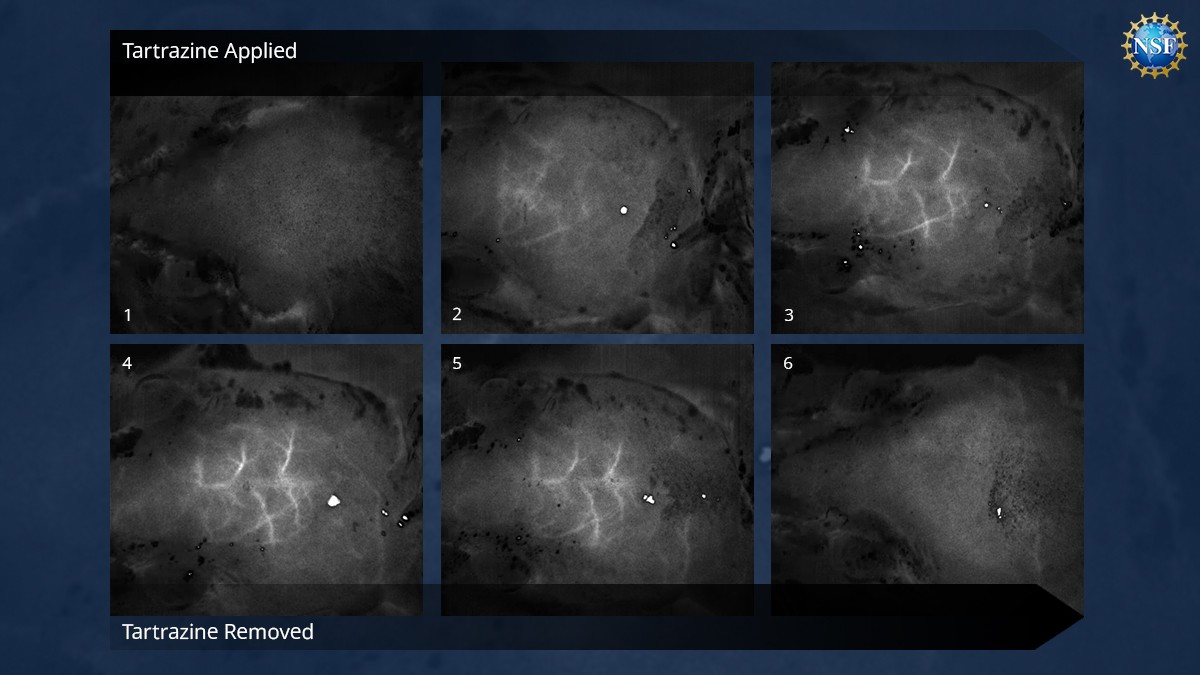

After initial experiments showed that tartrazine could turn slices of chicken breast transparent, the team turned to lab mice. They rubbed a tartrazine solution onto the rodents' scalps and then observed the animals under a microscope.

"It takes a few minutes for the transparency to appear," study lead author Zihao Ou, an assistant professor of physics at the University of Texas at Dallas, said in a statement. "It's similar to the way a facial cream or mask works: The time needed depends on how fast the molecules diffuse into the skin."

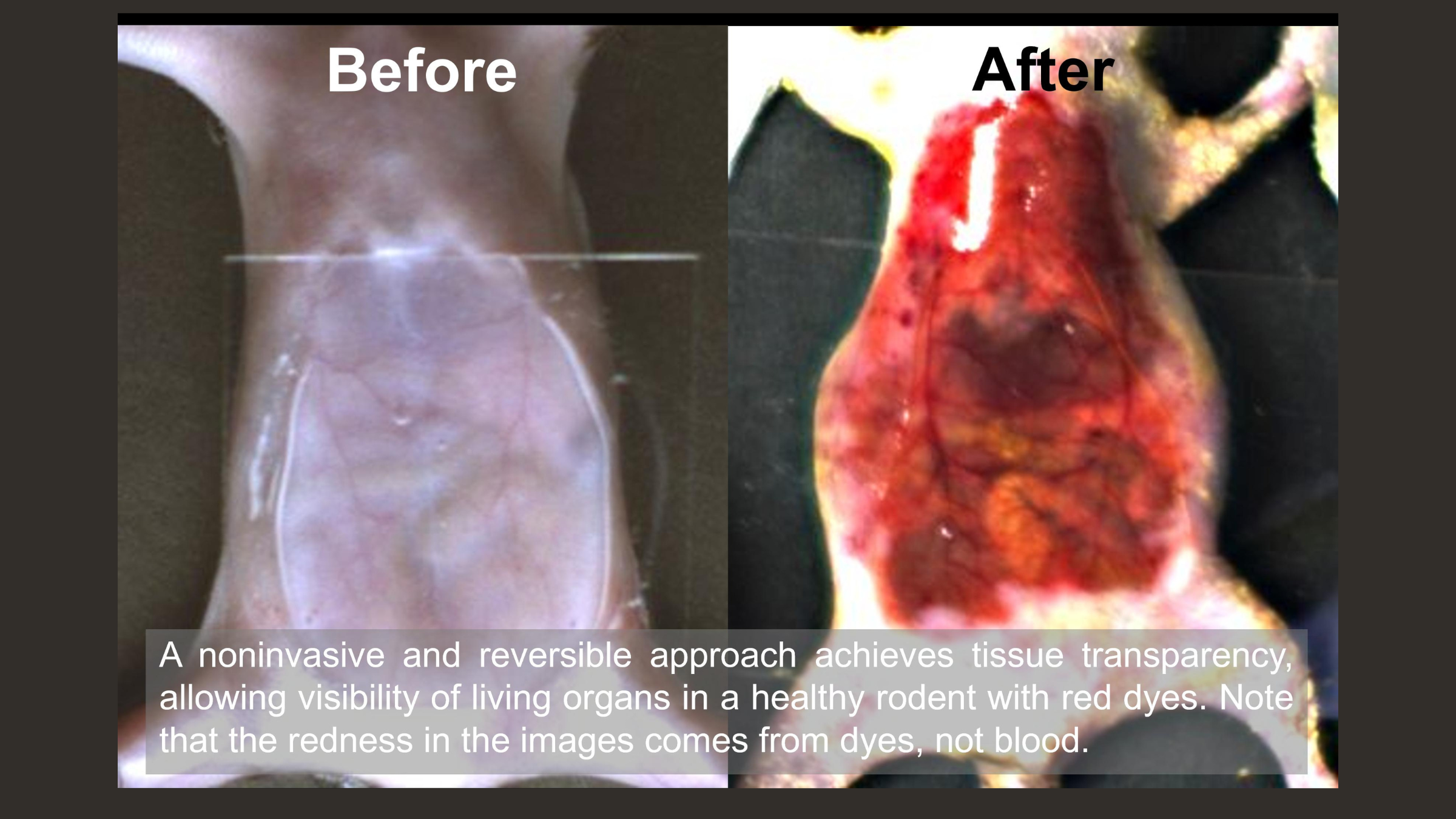

Once the solution set in, the researchers were able to see blood vessels streaming across the surface of the mice's skulls at a micrometer-level (0.001 millimeters) resolution. In a separate experiment, they applied the tartrazine solution to the mice's abdomens. Within minutes, they could clearly identify organs such as the liver, small intestine and bladder. They could even see muscles within the gut contracting, as well as subtle motions of the abdomen caused by breathing and the heart beating.

The transparency could be reversed by rinsing the mice's skin with water, ridding them of the food-dye solution. Any excess tartrazine that was absorbed into the body was excreted in the rodents' urine within 48 hours of application.

The treatment induced "minimal inflammation" in the short term, the researchers wrote in the study, but it didn't appear to have any long-term effects on the animals' health, as measured by changes in their body weight and blood-test results.

"This approach offers a new means of visualizing the structure and activity of deep tissues and organs in vivo [in the living body] in a safe, temporary, and noninvasive manner," Christopher Rowlands and Jon Gorecki at Imperial College London, wrote in a commentary of the new study. Neither Rowlands, a bioengineer, nor Gorecki, a physicist, was involved in the new work.

The new technique hasn't been tested in humans yet. Our skin is about four times thicker than that of mice, which would make it harder for tartrazine to be absorbed into its deepest layer. But if future studies show that the dye works in humans and it is safe, it could become a useful medical tool, the research team says.

"Looking forward, this technology could make veins more visible for the drawing of blood, make laser-based tattoo removal more straightforward, or assist in the early detection and treatment of cancers," study co-author Guosong Hong, an assistant professor of materials science and engineering at Stanford University, said in a statement.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30.