Super-realistic prosthetic eyes made in record time with 3D printing

Scientists can now 3D print more-realistic prosthetic eyes in a fraction of the time and effort required by traditional approaches.

Extremely realistic-looking prosthetic eyes can now be 3D-printed in a fraction of the time it would normally take to produce the eyes by hand, scientists demonstrate in a new study.

This 3D-printing technology could be used to help create realistic prosthetic eyes for the 8 million people worldwide who need at least one, either due to a birth defect that causes an eye to be small or missing or because they've lost an eye.

The new technology can create a prosthetic eye in just 90 minutes, compared with the eight hours it would normally take a skilled technician, or ocularist, to produce one by hand. The 3D-printed eyes require five times less labor to make than traditional methods, the scientists behind the technology wrote in a new paper published Tuesday (Feb. 27) in the journal Nature Communications.

The 3D-printed eyes also look more natural than traditional prostheses; this could help improve a patient's self-confidence in using the devices.

"Patients are very conscious about wearing a prosthesis, and they don't want others to notice," Johann Reinhard, lead study author and a researcher at the Fraunhofer Institute for Computer Graphics Research in Germany, told Live Science. "With these more realistic eyes, it might help them to participate more in society," he said.

Related: Scientists develop 'crying' model of human eye tissue

So far, this approach has been used to create prosthetic eyes for more than 200 adult patients at the Moorfields Eye Hospital (MEH) in London, including 10 people who were described in detail in the new study, Reinhard said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

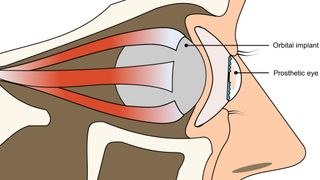

Normally, to craft a prosthetic eye, an ocularist makes a mold of the patient's eye socket by temporarily filling the cavity with a soft molding material. That material is then removed and used as a template to make a wax impression that can fit in the person's eye socket. The wax is smoothed, tested and reshaped until it fits comfortably and is then used to make a plastic version. The final, plastic eye is hand-painted to match the patient's healthy eye.

Such artificial eyes usually have to be replaced every five to 10 years, in part due to wear and tear to the plastic that they're made of. However, because this is a manual process, there's always a chance that subsequent eyes produced for the same person could differ in their appearance and shape.

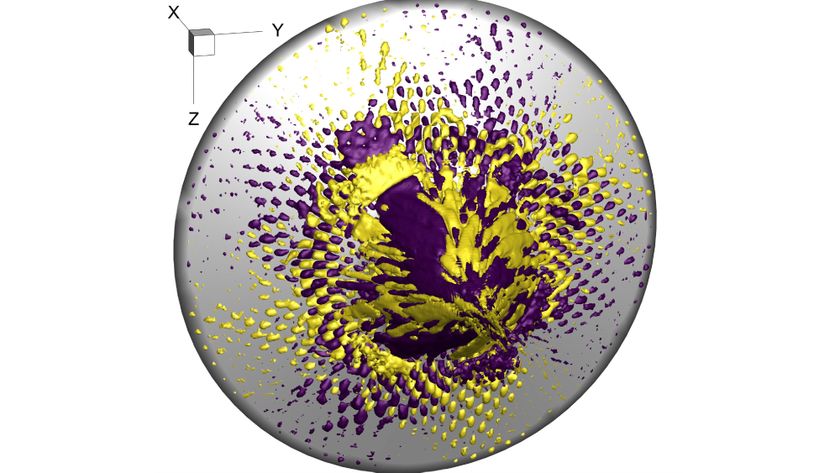

Instead, the new printing approach involves taking a specialized image of a patient's empty eye socket and of their healthy eye. These images are then processed and used to draft blueprints that can be sent to be 3D-printed in the lab. This printing process usually takes around 90 minutes, but it can be sped up if multiple eyes are printed at once — for instance, it would take just 10 hours to print 100 prosthetic eyes, Reinhard said.

These 3D-printed eyes closely replicate the color, size and structure of the patient's healthy eye and are particularly good at capturing the colored part of the eye, known as the iris, and the white part of the eye, called the sclera. Once finished, the eyes take 15 to 30 minutes to be installed by an ocularist, Reinhard said.

About 80% of adults in need of prosthetic eyes could theoretically have one made this way, the team said. However, this wouldn't be possible for all patients, such as those who have a very complex eye socket, as the software wouldn't be able to find a matching shape for the prosthetic eye, Reinhard said.

More data are needed to see if this technique could also be used to make prosthetic eyes for children, which would require more regulation, Reinhard said.

For now, though, the team intends to test the approach in more clinics. Sometime this year, they hope to publish the results of a clinical trial that explored the long-term performance of these 3D-printed eyes in 40 patients at MEH, compared with the performance of manually made prostheses.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30. (emily.cooke@futurenet.com)