CDC data reveal plummeting rate of cervical precancers in young US women — down by 80%

New CDC data on falling rates of precancerous cervical lesions in the U.S. underscore the benefits of HPV vaccination.

Far fewer cervical cancer screening tests are coming back positive for precancer in the United States thanks to the widespread adoption of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, which prevents the main cause of cervical cancer.

Cervical cancer develops in cells of the cervix, which connects the womb to the vagina. Each year, around 11,500 people are diagnosed with cervical cancer in the U.S., and 4,000 people die annually from the disease.

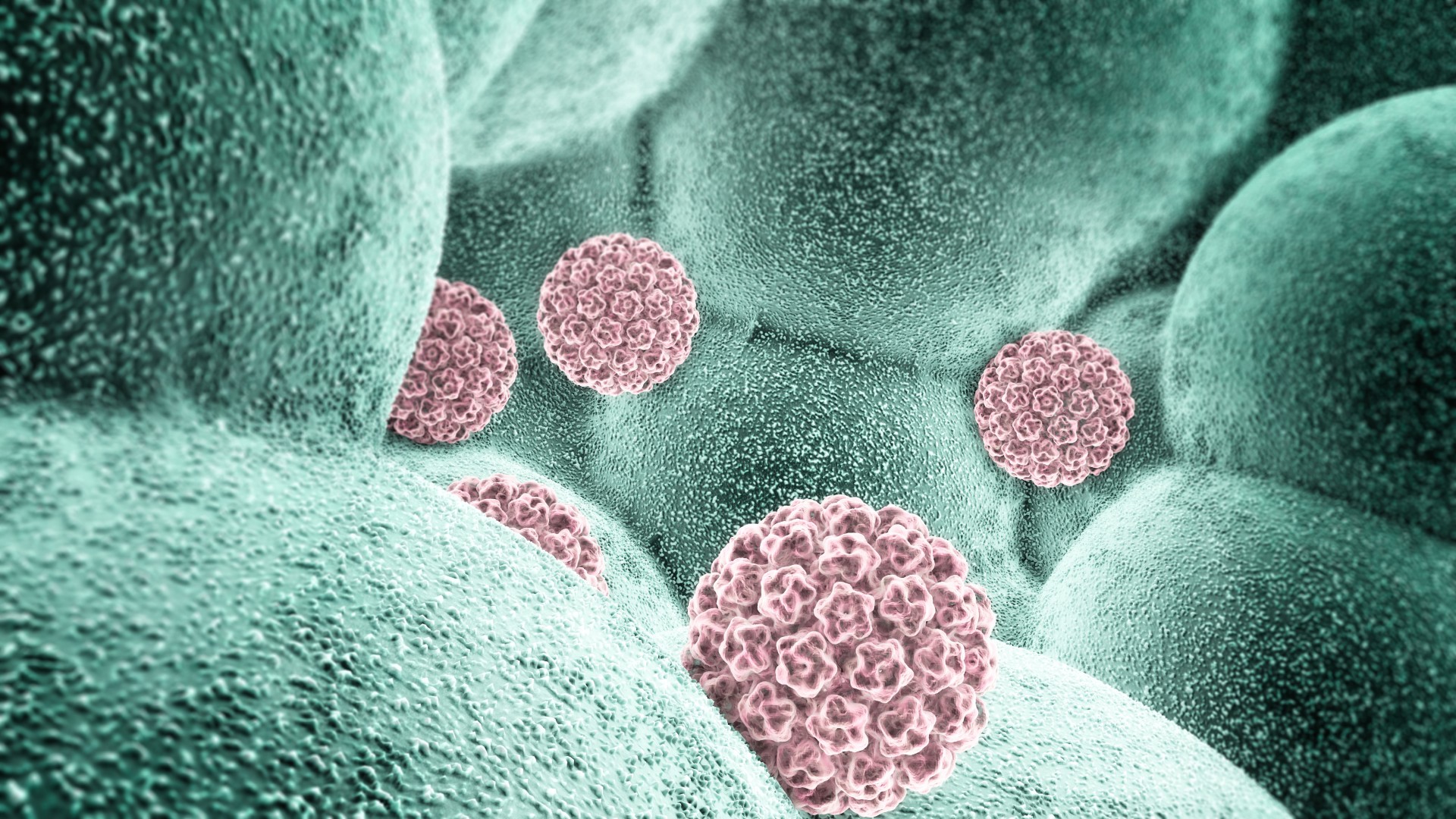

Nearly all cervical cancer cases — over 90% — are caused by infection with high-risk types of HPV, viruses that can spread from person to person through sexual contact. The disease can happen to anyone with a cervix at any age, but it is most commonly diagnosed in people ages 35 to 44.

The HPV vaccine, which was first approved for use in the U.S. in 2006, protects against the HPV infections that cause most cervical cancer. Since the vaccine's introduction in the country, U.S. rates of HPV vaccination have increased steadily, reaching an estimated 76.8% of the eligible population in 2023.

Related: Cervical cancer deaths have plummeted among young women, US study finds

Now, according to a new analysis of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data, rates of precancerous lesions detected during cervical cancer screening have fallen by about 80% since 2008.

The goal of cervical cancer screening, which includes "Pap smears," is to detect precancerous lesions, meaning groups of cells in the cervix that have the potential to become cancerous. If successful, screening detects these cells years before they become tumors, making it easier to treat the condition. At that early stage of the disease, treatment may involve laser surgery or cryotherapy.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To analyze the results of cervical cancer screening through time, the new analysis, published Feb. 27 in the CDC's Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), looked at a mix of private and public insurance claims and survey data. It focused on women ages 20 to 24, the age group that's most likely to be vaccinated for HPV, as well as women ages 25 to 29, who were comparatively less likely to be vaccinated.

The CDC recommends the HPV vaccine to all children ages 11 to 12. However, the vaccination series can be started as early as age 9, as well as later in life, for those who weren't vaccinated as children. People usually receive two or three doses of the vaccine, spaced one to 12 months apart.

Meanwhile, the American Cancer Society recommends that people should start cervical cancer screenings at age 25.

The new MMWR suggests that HPV vaccination efforts have been successful at driving down precancer rates. Notably, precancer comes in several forms, including moderate and severe, and the latter is more likely to turn cancerous. The rates of both types of precancer fell over the study period.

Specifically, the incidence of moderate precancer fell by 79% in women ages 20 to 24, while the more serious lesions decreased by 80% during the same time period, the scientists found. Rates of the severe lesions also declined by 37% among women ages 25 to 29.

"This report published in MMWR adds more evidence showing the effectiveness of HPV vaccination for prevention of pre-cancers of the cervix," Heather Brandt, director of the HPV Cancer Prevention Program at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital in Tennessee, who was not involved in the research, told Live Science in an email.

The new report didn't directly measure whether HPV vaccination caused the decrease in precancerous lesions. However, numerous other studies have shown that the vaccine slashes cervical cancer rates.

The report speaks to the importance of having at least one dose of the HPV vaccine before age 15, Dr. Diane Harper, a family physician and clinical research expert in HPV-associated diseases who was not involved in the research, told Live Science in an email.

Harper said she hopes that, soon, children as young as 4 to 6 years old could be offered the HPV vaccine, when they receive their second dose of the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine, she told Live Science in an email. This would ideally simplify things and encourage more people to be vaccinated against HPV, she suggested.

Disclaimer

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30. (emily.cooke@futurenet.com)

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.