New self-swab HPV test is an alternative to Pap smears. Here's how it works.

There's a new way to screen for high-risk HPV, a viral infection that can lead to cervical cancer. This alternative method of collecting samples for cervical cancer screening doesn't require a speculum.

A new option for cervical cancer screening gives patients a less-invasive alternative to conventional tests.

These new "self-collection tests" are scheduled to arrive in doctor's offices nationwide this month. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved self-collection as a method to detect human papillomavirus (HPV), the leading cause of cervical cancer, in May. Screening tests are intended to flag people at high risk of cancer or precancer, not to diagnose the disease.

This FDA approval enables patients to collect their own clinical samples for cervical cancer screening. With the rollout of these tests, the U.S. joins Australia, Canada, the Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden, where self-swabbing for HPV is already widely used.

For now, the samples, collected from the vaginal canal, must still be gathered in health care settings, such as doctor's offices. Other countries have allowed at-home self-sampling for HPV, but the method is still pending FDA approval in the U.S.

Here's what you should know about the newly available self-collection tests.

How is HPV related to cervical cancer?

HPV is a common sexually transmitted infection that's primarily transferred through sexual intercourse or skin-to-skin contact. Most sexually active people will contract at least one type of HPV in their lifetime, but the infection normally resolves on its own.

Though more than 30 types of HPV can infect the genitals, only a small number — referred to as "high-risk" HPV — are associated with cancer. Low-risk HPV tends to have no symptoms and clears on its own, although sometimes, genital warts may appear. Nonetheless, this low-risk type of infection rarely leads to cancer.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Almost all cervical cancer cases are caused by long-term infections with high-risk HPV. A high-risk HPV infection that doesn't go away can lead to abnormal cell growth, which can then turn cancerous down the line.

The HPV vaccine can protect against most cases of cervical cancer. A 2024 study in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute found zero incidence of invasive cervical cancer among young Scottish women who'd received at least one dose of HPV vaccine. Moreover, women who'd received three doses of the vaccine — the number generally recommended — were significantly less likely to develop cervical cancer than unvaccinated women.

In the event someone develops high-risk HPV, there is no cure, but abnormal cervical cells can be removed before they cause cancer.

What do cervical cancer screening tests look for?

There are two standard ways to check for cervical cancer: an HPV test and a Pap test.

An HPV test can detect the genetic material of high-risk strains of HPV that, if left untreated, can cause cancer. A Pap test, also called a Pap smear or cervical cytology, checks for changes in cervical cells that could lead to cancer. These changes include the cell's nucleus, which holds its DNA, growing abnormally large, Dr. Nicholas Wentzensen, a senior investigator at the National Cancer Institute's Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, told Live Science.

An HPV test can also be performed alongside Pap tests in what's called a co-test. The combined test can detect high-risk HPV and cervical cell changes using the same sample. The recommendations for who should get which test and how frequently varies with age and other health factors (see later section for details).

It is important to note that these are not diagnostic tests. Instead, their intent is to flag individuals at high risk of developing cancer or precancer. A positive result on any of these tests would require further testing — often a colposcopy-directed biopsy — to receive a diagnosis. .

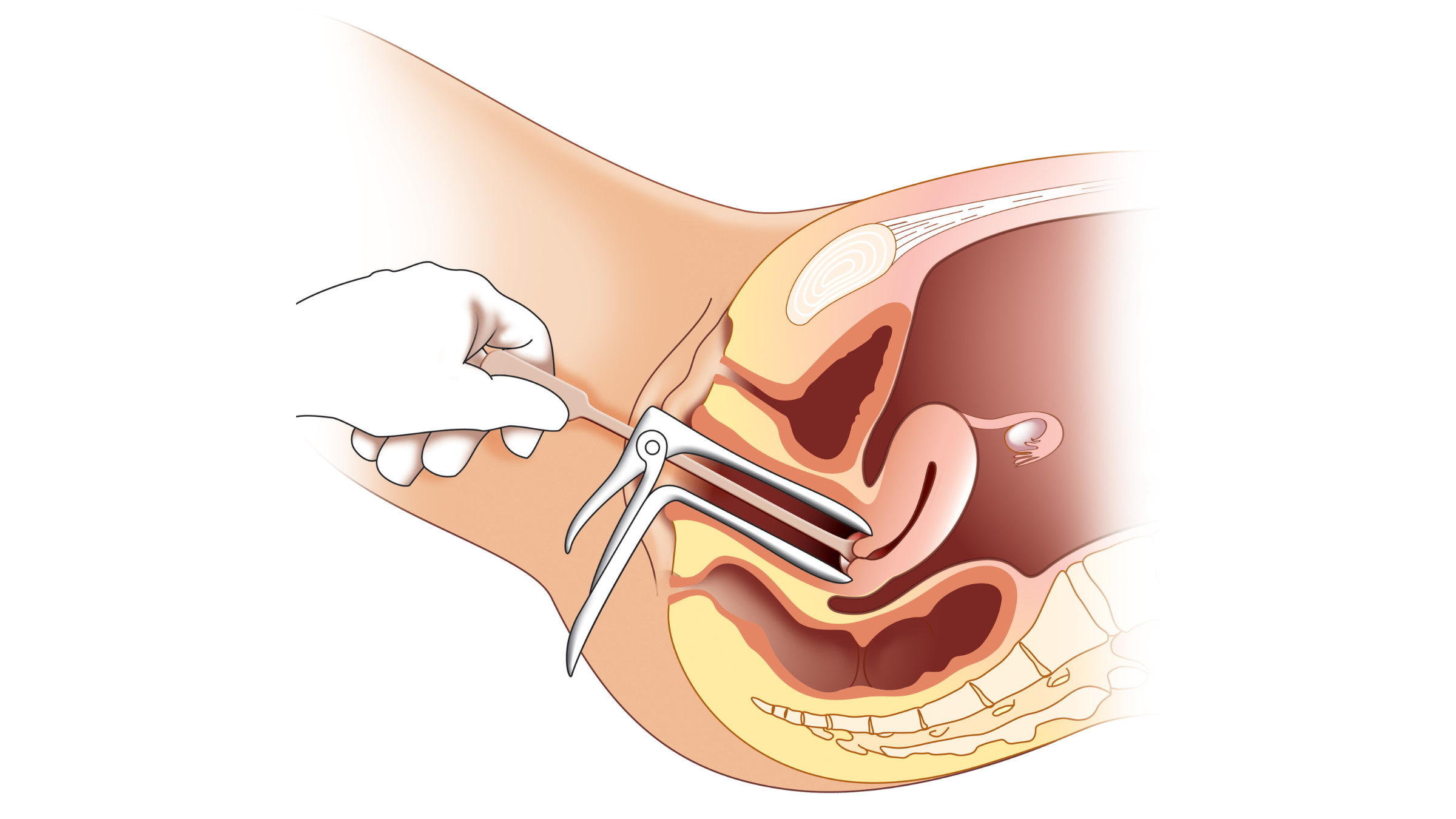

Both conventional HPV tests and Pap tests have traditionally required a sample of cells collected from the cervix, the narrow canal that connects the uterus and vagina. during a pelvic exam performed by a doctor. The sample, taken during a pelvic exam*, is taken by a doctor who inserts a speculum into the vagina to widen it and then scrapes the cervix with a brush or spatula.

But now, the FDA has approved a far less invasive option: patients can now self-sample in a health care setting and use cells from the vagina, rather than the cervix. Studies have shown that samples from the vagina are just as effective for detecting HPV as those taken from the cervix and that no significant difference exists between self-collected and doctor-collected samples for HPV detection.

*Note that cervical cancer screenings and pelvic exams are not the same thing, although they're often performed at the same time. Pelvic exams are used to check on the health of female reproductive organs.

Why is cervical cancer screening important?

Cervical cancer screening has been found to greatly reduce death rates from cervical cancer. For example, in England, regular screening is estimated to reduce cancer mortality by 70%, according to a 2016 study published in Nature. The idea is that, with routine screening and follow-up tests, cancer can be detected and treated early before it progresses to a more advanced, treatment-resistant stage of the disease.

The National Cancer Institute estimates that about 11,500 new cases of cervical cancer are diagnosed in the U.S. every year. About half of these cases end up being diagnosed in patients who were not adequately screened, per current guidelines, or who had not undergone any screening at all.

Ideally, the tests prevent cancer deaths by detecting precancerous changes in cells early, when treatment is most beneficial. However, they can also pick up full-blown cancer in the event it's already developed. In either case, a positive screening test would then lead to formal diagnostic testing.

How do the new self-collection tests work?

If opting to use the new self-collection tests, a patient should receive instructions on how to do so from their medical provider. The patient will complete the test in the clinic, but no medical supervision is required during the self-collection itself. In other words, a doctor doesn't need to be in the room when the sample is collected.

Generally, the patient is instructed to insert a long cotton swab into the vagina and then gently swirl it for 20 to 30 seconds to collect an adequate sample. The sample is then left at the health care provider's office, and from there, it is sent to a lab for analysis.

What are the advantages of self-collection compared with a Pap smear?

The new self-collection option has the potential to increase the number of people who get cervical cancer screenings across the U.S. The hope is that these tests, which are more convenient and less invasive than the traditional screening approaches, will help reach patients who may forgo Pap tests for various reasons.

For many patients, screenings that involve a speculum can mean physical and emotional discomfort, said Dr. Ilana Cass, a gynecologic oncologist at Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center and a professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. A Pap smear can be triggering particularly for patients with a history of sexual violence, older patients with more sensitive vaginal tissues, and people with gender dysphoria.

"If we are able to invite more people in for testing through these expanded technologies, who would have previously been uncomfortable or would have been uninterested, this is really great. This is progress," Cass told Live Science.

Are there any downsides to the self-collection tests?

A meta-analysis of studies, published in Nature, found that self-collected vaginal samples are comparable to cervical samples collected by a doctor, in terms of their ability to reveal HPV. One study included in the analysis found that tests that used self-collected samples were about 89% accurate at detecting HPV. By comparison, doctor-collected samples garnered nearly 88% accuracy.

Nonetheless, patients may have concerns about self-collection, Cass noted. These are often legitimate worries about performing the test correctly and getting a good enough specimen. Although self-collection will always be somewhat susceptible to user error, the method is highly sensitive — even if a patient collects only a small number of cells, the tests can adequately detect HPV.

Who should be screened for cervical cancer and how often?

The American Cancer Society (ACS) recommends that regular cervical cancer screenings begin at age 25. These guidelines are the most up-to-date, as the recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force — another expert group — are currently being revised, Wentzensen told Live Science.

According to the ACS guidelines:

- Adults with a cervix who are between the ages of 25 and 65 should have a primary HPV test every five years. A primary HPV test is one that tests for HPV alone and is not combined with a Pap test.

- Alternatively, a co-test, which combines an HPV test and a Pap test, can be done every five years.

- Or, a Pap test alone can be done every three years.

It is important to note, however, that primary HPV tests are the gold-standard screening method to prevent cervical cancer. They are better than Pap smears at finding precancerous changes in cervical cells.

More frequent screening schedules than the one described above may be recommended for patients with a personal or family history of cervical cancer, or for those who have HIV or a compromised immune system. The important takeaway is to get screened regularly and follow through with recommended follow-up tests, to catch abnormalities early when treatment has the greatest chance of success.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Julie Goldenberg is a journalist based in New York City. She was a former associate editor at AARP where she reported on aging in America. Her work has appeared in AARP the Magazine, AARP.org, and Forbes. She holds a Master of Science degree in Journalism from Columbia University's Graduate School of Journalism and a Bachelor's degree in psychology from McGill University.