Brain fog in long COVID may be linked to blood clots

A new study links long-COVID-related brain fog to two blood-clotting proteins.

The debilitating brain fog often experienced by people with long COVID may stem from blood clots, new research suggests.

Long COVID describes myriad symptoms that linger for weeks to years after a COVID-19 infection. Some people with the condition experience problems with blood flow and lung capacity, which have been linked to tiny, abnormal blood clots. Researchers have suggested that blood clots may also drive neurological symptoms of long COVID, like brain fog, which can disrupt people's ability to focus, remember and execute tasks.

The new study, published Thursday (Aug. 31) in the journal Nature Medicine, backs this idea linking blood clots to brain fog. However, it doesn't fully connect the dots to show how the clots might actually damage nerves or the brain to trigger brain fog.

"I feel optimistic that the science is beginning to give us real insights into what the causes [of long COVID] are and then the potential treatments," study co-author Chris Brightling, a clinical professor in respiratory medicine at the University of Leicester in the U.K., told Politico.

"What I'm still disappointed in is … there's still a lot of patients that are suffering that haven't yet fully recovered," he said. "And we don't know how long it will take for them to recover."

Related: 85% of COVID-19 long-haulers have multiple brain-related symptoms

The new research used data from nearly 1,840 adults who were hospitalized with COVID-19 in the U.K. in 2020 and 2021. This narrowed the study's focus to unvaccinated patients who'd developed severe infections, so it's unclear how well the results extend to vaccinated people and those who develop long COVID after mild or asymptomatic infections.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As part of the post-hospitalization COVID-19 (PHOSP-COVID) study, the participants gave blood samples at the time of hospitalization and then, six months and 12 months later, took cognitive tests and filled out questionnaires, Science reported.

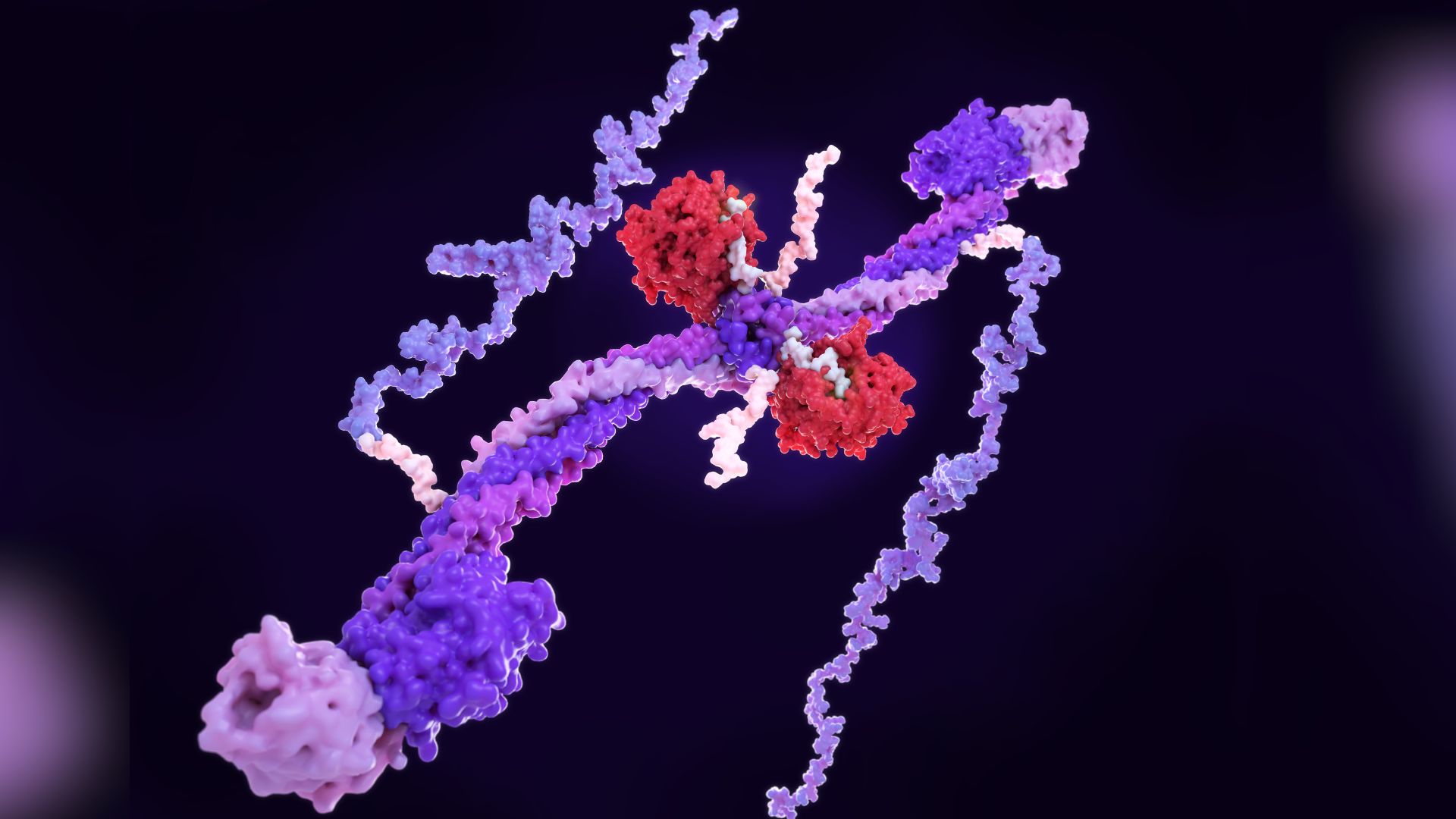

Two proteins involved in blood clotting, called fibrinogen and D-dimer, jumped out as key predictors of people's cognitive problems down the line. Fibrinogen, made by the liver, serves as the major structural component needed to form a blood clot, and D-dimer is a protein fragment released when blood clots break down.

Compared with those who had less fibrinogen, hospitalized patients with the highest levels of fibrinogen scored worse on memory and attention tests and rated their cognition as worse on surveys. Similarly, people with high D-dimer levels later rated their cognition more poorly on subjective surveys than people with low D-dimer did. The high-D-dimer group was also more likely to report problems with their ability to work six and 12 months out from hospitalization.

The two blood-clotting proteins have previously been linked to severe COVID-19, and separately, fibrinogen alone has been associated with cognitive issues and dementia, Science reported. At this point, it's unknown how the proteins might be driving brain fog in long COVID.

Lead study author Dr. Maxime Taquet, a clinical psychiatrist at the University of Oxford, told Science that fibrinogen-related blood clots may be derailing blood flow to the brain or perhaps directly interacting with nerve cells. D-dimer may be more linked to clots in the lungs and breathing issues, which were commonly reported in the high-D-dimer group, he said.

"Future research should look at whether treatment targeting blood clotting, for example blood thinners, might help people with these symptoms," Dr. Aravinthan Varatharaj, a clinical lecturer in neurology at the University of Southampton who was not involved in the study, told Politico. This use for blood thinners would have to be rigorously tested in trials.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.