Newfound autoimmune syndrome tied to COVID-19 can trigger deadly lung scarring

A surge in cases of a rare autoimmune disease during COVID-19 waves in England led to the discovery of a new syndrome.

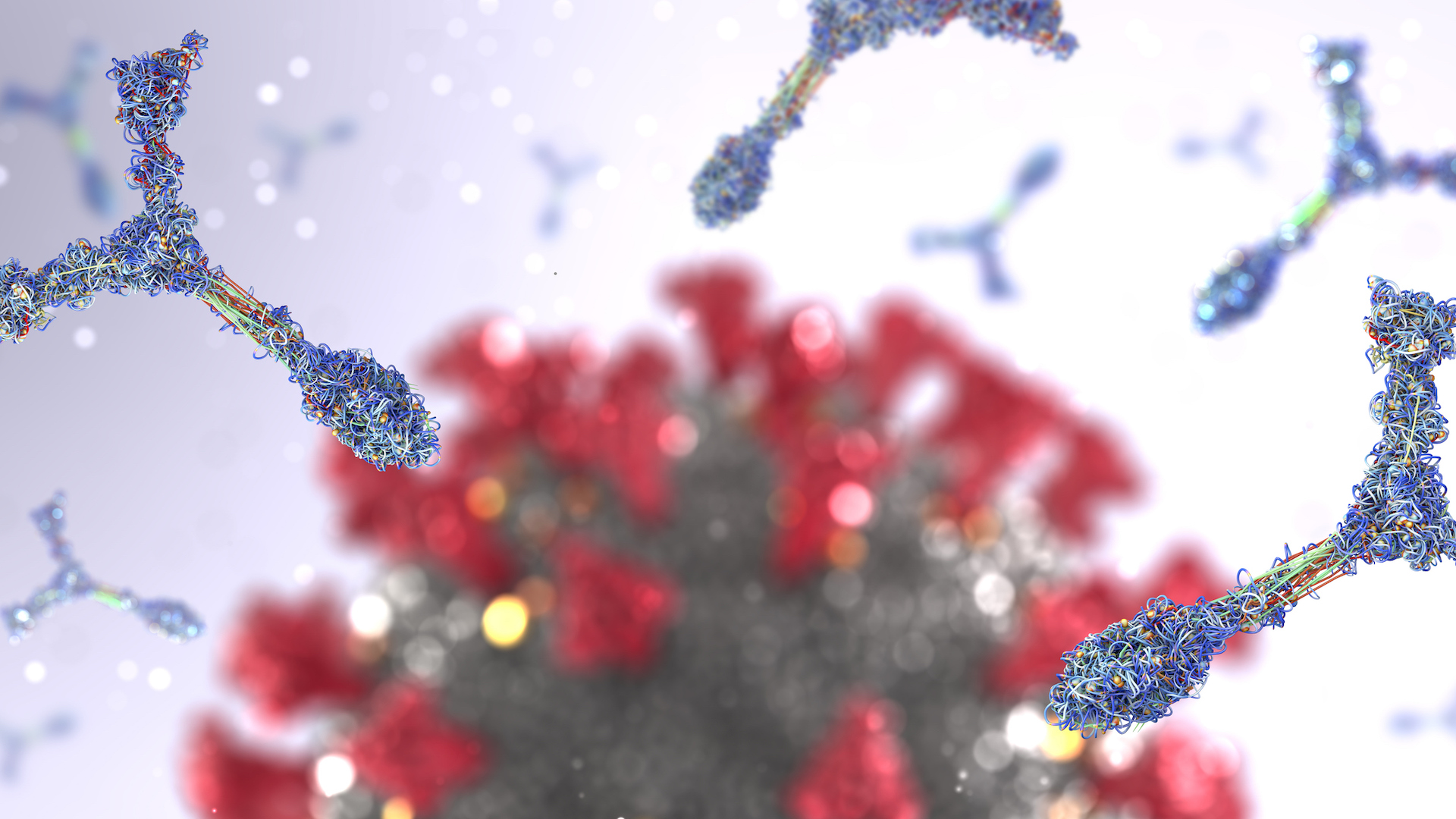

Researchers have discovered a new autoimmune syndrome associated with COVID-19 that can cause life-threatening lung disease.

The syndrome — which scientists have dubbed "MDA5-autoimmunity and interstitial pneumonitis contemporaneous with the COVID-19 pandemic," or MIP-C for short — is a rare, serious condition in which the immune system inadvertently attacks the body. In the worst cases, the lungs end up so scarred and stiff that the only way to save the patient is a full lung transplant.

However, only a portion of cases involve the lungs. "Two-thirds of our cases did not have lung disease," said Dr. Dennis McGonagle, a rheumatologist at the University of Leeds in the U.K. who first started piecing together the patterns of the new disease. "But we did see that eight cases rapidly progressed and died despite all the high-tech therapies we could throw at them."

In all, McGonagle and his colleagues have identified 60 cases of the syndrome so far. They published a study of the cases May 8 in the journal eBioMedicine.

Related: COVID-19 linked to 40% increase in autoimmune disease risk in huge study

The disease looks similar to the known condition MDA5 dermatomyositis, which is seen almost entirely in women of Asian descent, McGonagle told Live Science.

In it, patients experience joint aches, muscle inflammation and skin rashes, and in two-thirds of cases, they develop life-threatening lung scarring. MDA5 dermatomyositis happens when the immune system attacks one of its own: a protein called MDA5 that normally helps detect RNA viruses. Such viruses include those that cause influenza, Ebola and COVID-19.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To better understand autoimmunity against MDA5, hospitals associated with the University of Leeds in Yorkshire began screening people with autoimmune symptoms for antibodies against the protein. Back in 2018, they found three patients who fit the bill. They saw another three cases the following year and eight more in 2020 — but then, in 2021, there were suddenly 35.

The patients carried anti-MDA5 antibodies, but their disease was different from the previously known dermatomyositis. Most cases didn't involve the lungs; new patients were mostly white rather than of Asian descent; and affected women only slightly outnumbered men.

McGonagle reached out to Dr. Pradipta Ghosh at the University of California, San Diego to investigate further. Ghosh had been using a computational framework to take medical testing data and find common threads between conditions. Her team previously published work about lung scarring in COVID-19, as well as MIS-C, an inflammatory syndrome that arises in some children after they have COVID-19.

The team compared medical records from patients with the mystery condition, patients with COVID-induced pneumonia and patients with lung scarring unrelated to viruses. Patients with pneumonia and the autoimmune condition both showed increased activity in the gene IFIH1, which provides the blueprint for MDA5.

Most patients with the mystery syndrome did not have a recently confirmed case of COVID-19 in their records, but it's probable many were exposed to the coronavirus and had either mild or asymptomatic disease, McGonagle said, given the timing of their cases. More than half of the patients were confirmed vaccinated for COVID-19, although which specific vaccine each person got is unknown.

Related: Master regulator of inflammation found — and it's in the brain stem

The new study suggests that exposure to the coronavirus's RNA, COVID-19 vaccines or both may sometimes trigger the production of anti-MDA5 antibodies, McGonagle said.

Normally, MDA5 activates when it senses viral RNA in a cell and prompts the body to make antibodies against the virus. But in people with MIP-C, this immune response goes wrong. Either the body mistakes the MDA5 protein as foreign and attacks it, or the RNA kicks off such a strong immune response that the body's own proteins, including MDA5, become targeted for immune attack, McGonagle suggested.

The activation of IFIH1 came with a flood of an inflammatory protein called interleukin-15 (IL-15), the researchers found. IL-15 activates a class of immune cells that normally kill infected cells but can sometimes go rogue and attack the body's own cells.

"Our work should alert doctors to start thinking that if you see there was some exposure to virus or the vaccine or just a contact to somebody who had COVID and they come in with joint pains, rashes, aches … let's look at the lungs," Ghosh told Live Science.

The researchers are still collecting data, but new cases of MIP-C now appear to be slowing. In 2022, Yorkshire saw 17 cases — about half of 2021's rate. The intense RNA exposure of the widespread COVID waves of 2021 plus mass vaccination may have driven that year's spike, McGonagle theorized. The researchers said they have received reports of possible MIP-C from other regions, as well.

The study also uncovered a particular genetic sequence within the IFIH1 gene that, in people who had that sequence, seemed to prevent the runaway IL-15 inflammatory response. The next step is to understand why others are vulnerable to it, Ghosh said.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.