Could Ozempic be used to treat addiction? Studies hint yes, but questions remain

In animal studies, the weight-loss drug Ozempic has shown promise as an anti-addiction medicine. Whether it could work the same in humans remains to be seen.

The diabetes drug Ozempic has become a household name as a powerful weight-loss treatment. Its cousin Wegovy, specifically marketed for weight loss, contains the same active ingredient — semaglutide — and is similarly skyrocketing in popularity.

But some people say the drugs have helped them do more than lose weight — people struggling with addiction are reporting that the drug has caused them to completely lose interest in alcohol, drugs and even obsessive shopping habits, The Atlantic reported in May.

Though these anecdotes may seem random, they are actually supported by more than 20 years of research, experts told Live Science. Animal studies have found that drugs like semaglutide, which mimic a gut hormone called glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), seem to suppress drug-seeking behaviors. Other studies in humans have found that the drugs, called GLP-1 agonists, could help some people with alcohol use disorder drink less and people who smoke drop cigarettes.

However, animal studies are not always reliable in determining if a drug will work the same way in people, and formal clinical trials testing GLP-1 agonists as addiction treatments are ongoing. Yet, scientists have reason to be optimistic, with research pointing to the drugs' effect on a major system in the brain involved in addiction: the reward pathway.

Related: 'Magic mushroom' psychedelic could treat alcohol addiction, trial finds

"Unfortunately, the translation [of new drugs] from animals to humans is always challenging," said Dr. Lorenzo Leggio, a physician-scientist at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) who studies the effects of GLP-1 agonists on addiction. But he said scientists who study GLP-1 agonists "are definitely excited" about the drugs' potential to help people with addiction.

As early as the 1980s, researchers recognized that GLP-1 wasn't produced only in the gut but also in parts of the brain, specifically in a part of the medulla, or lower brain stem, according to a 1986 study. By the 2010s, researchers were beginning to conduct studies, like one from 2011, to investigate the role this hormone might play in the brain’s system of reward and motivation. This system is called the mesolimbic pathway or "reward pathway."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

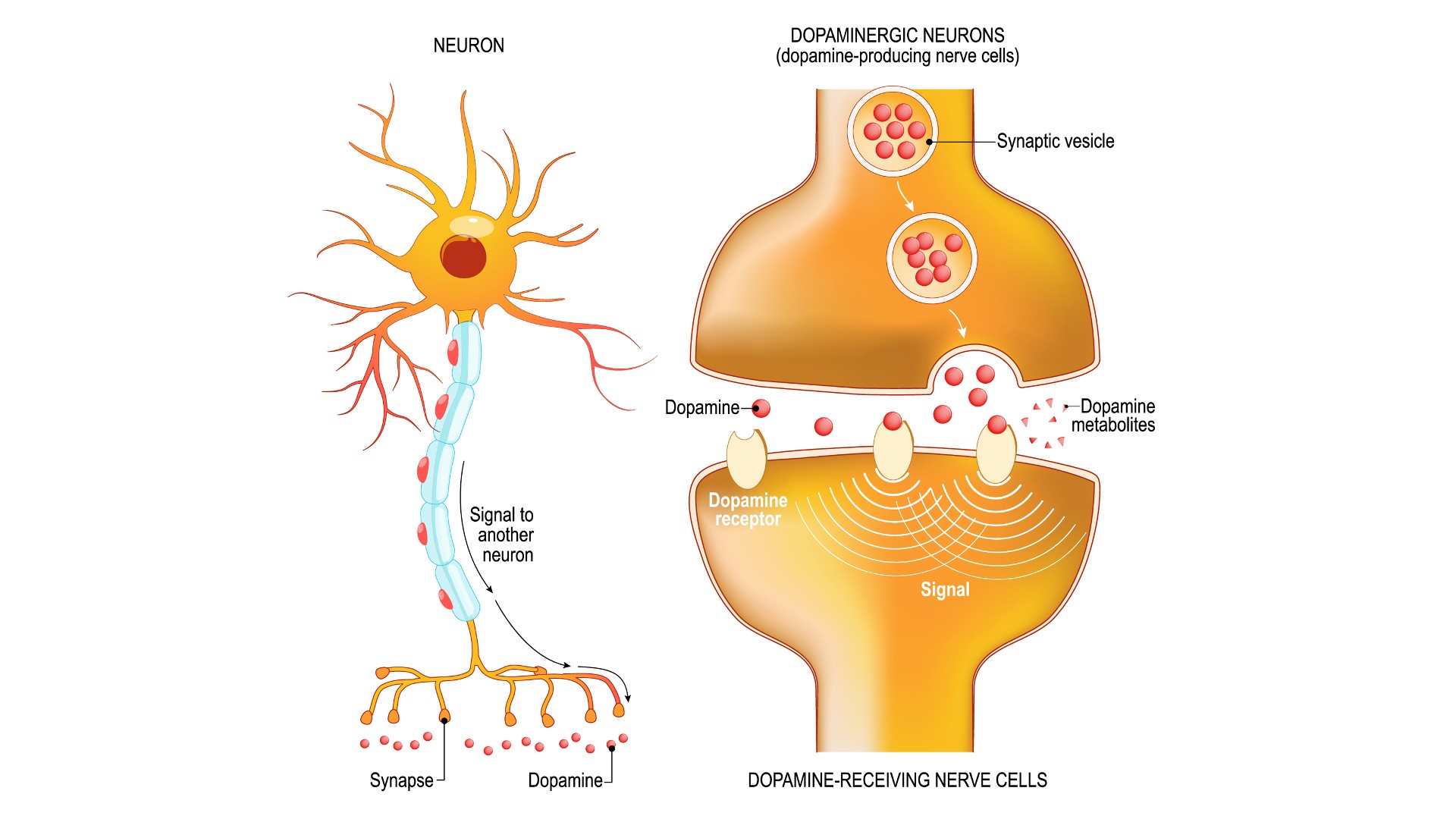

Part of the medulla called the solitary nucleus, receives incoming sensory information from the body, like taste signals from the tongue, while brain cells with GLP-1 receptors in the mesolimbic pathway help determine if you like a taste and if you'd like to experience that taste again. During rewarding experiences, whether they come from a good taste or an addictive drug, structures in the mesolimbic pathway activate and send dopamine to a part of the brain called the nucleus accumbens.

This structure plays key roles in generating pleasurable sensations and motivating reward-seeking behaviors. However, it seems that rather than activating this system, GLP-1 imposes limits on it. The hormone, along with the artificial version of it found in drugs like semaglutide, limits the brain’s release of the neurotransmitter dopamine, often called a “happy chemical.”

Food, water, sweets and addictive drugs all "cause a release of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens in the brain," said Patricia "Sue" Grigson, director of the Penn State Addiction Center for Translation. Binding to GLP-1 receptors, then, should reduce that dopamine response.

"Published data show that substances of abuse do not elicit that dopamine release when you have a GLP-1 agonist on board," she said. A 2020 study found some evidence that GLP-1 agonists might do this by impacting dopamine transporters in a brain region called the striatum, a main interface in the brain’s reward system, though they only found this effect in rats, not in mice and humans.

Studies on animal behavior also support the use of GLP-1 agonists to combat addiction. Grigson has been involved with several studies with the same basic design: A mouse or rat is trained to expect a drug, like alcohol or heroin, to be administered in response to certain cues. When the animal gets the cues but not the drug, the ones given GLP-1 agonists are less persistent in trying to seek out the drug. Animals that receive a "relapse" dose of the drug after having it withdrawn are even less likely to seek it out, Grigson said.

A 2022 study Grigson co-authored showed that when given the GLP-1 agonist liraglutide, rats were less likely to seek out heroin in response to drug-associated cues, stress or a dose of the drug itself, which would also normally prompt further drug-seeking.

So far, tests of drugs like semaglutide for human addiction have been limited, but researchers have seen some promising results.

In a 2021 study, people who took a GLP-1 agonist called exenatide in addition to using a nicotine patch were more likely to successfully quit smoking than those who used only the patch. A 2022 study found that a weekly dose of exenatide reduced the number of heavy drinking days in people with alcohol use disorder and obesity, but it didn't help participants of lower weights. Leggio said that researchers aren't sure what might cause a result like this. One possibility, he said, is that some people with obesity have more overlap in their brains between the response to food and the response to addictive substances.

There are several ongoing clinical trials that may soon tell us more. Leggio and Grigson are both involved in such trials and are eagerly awaiting the results — Grigson said one of hers should conclude in a few months. She also said unpublished research, led by a student of hers, exploring how GLP-1 agonists affect the brain suggests they work to treat addiction in two ways: by lessening the brain's reward associated with taking an addictive substance and by decreasing desire for the drug during withdrawal.

Although the stories from people who say semaglutide have helped them overcome addiction are encouraging, Leggio said, they are no substitute for actual research. Still, he appreciates the anecdotes.

"You cannot be a good physician-scientist if you don't listen to your patients," he said. "I'm excited for those people."

Rebecca Sohn is a freelance science writer. She writes about a variety of science, health and environmental topics, and is particularly interested in how science impacts people's lives. She has been an intern at CalMatters and STAT, as well as a science fellow at Mashable. Rebecca, a native of the Boston area, studied English literature and minored in music at Skidmore College in Upstate New York and later studied science journalism at New York University.