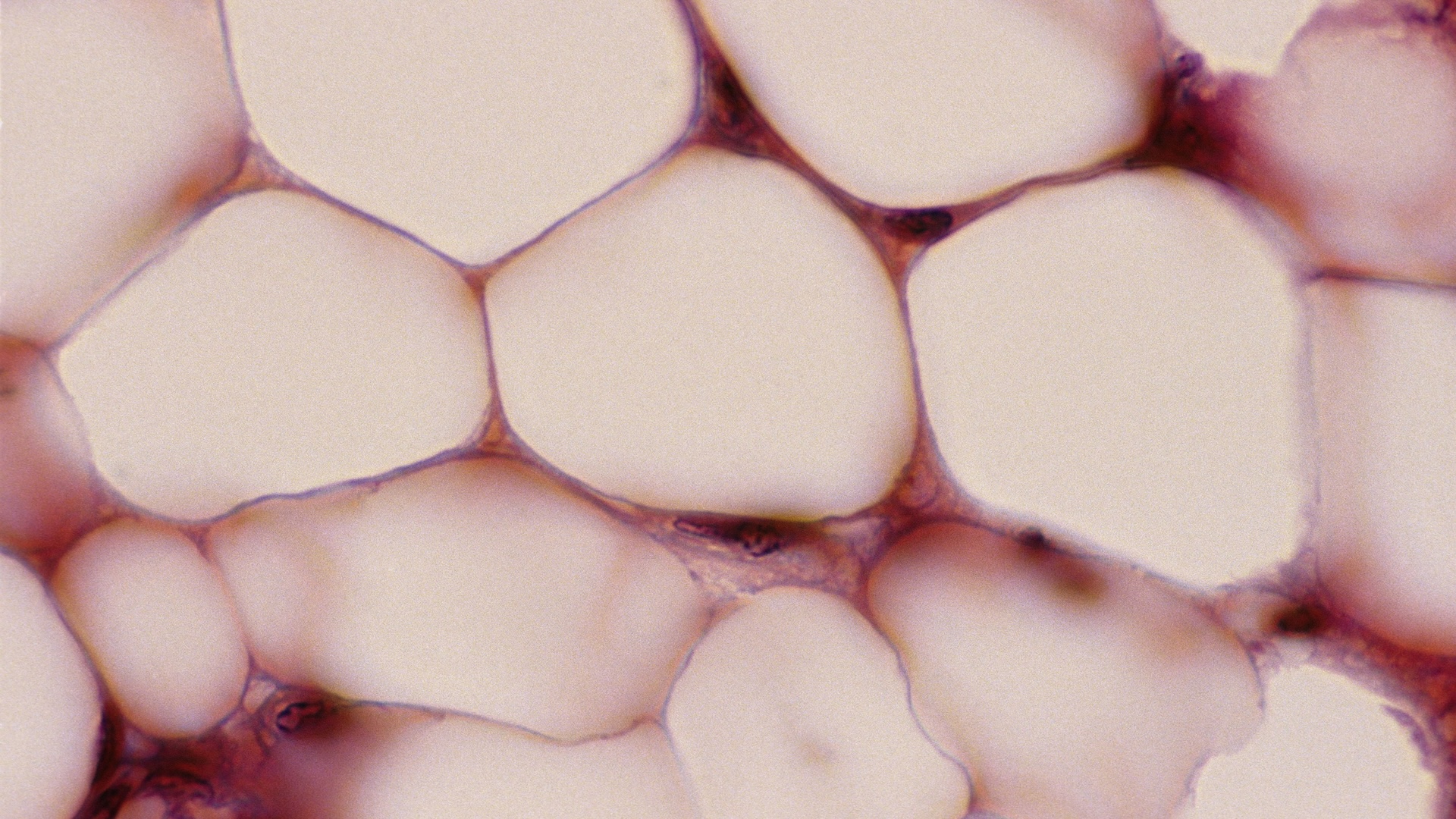

Fat cells have a 'memory' of obesity, study finds

Most people who lose weight through dieting will see it creep back up, leading to a cycle of "yo-yo dieting" that's hard on the body. A new study suggests fat cells keep a memory of previous weight gain, which may help to explain why this happens.

Losing weight can be a lot of work, which makes it all the more frustrating when, little by little, the weight creeps back. Now, a study suggests that fat cells retain a memory or past obesity, which may prime the cells to grow when exposed to high-fat foods.

The research "might add to the growing body of evidence that disproves lack of willpower as the underlying force behind 'weight cycling,'" said Dr. Katherine H. Saunders, an obesity physician at Weill Cornell Medicine and co-founder of FlyteHealth, a software and clinical services company for medical obesity treatment, who was not involved in the study.

Without weight-loss medications or bariatric surgery, most people will return to their original body mass within a few years of losing weight through a diet. This can lead to "yo-yo dieting." Scientists don't know why this happens, but genetics, environment and health history likely all play a role. Now, a study published Nov. 18 in the journal Nature adds an essential piece to this puzzle. Chemical modifications on DNA, or epigenetic markers, may help the cells retain a memory of their past state.

Related: Does it really take 20 minutes to realize you're full?

While DNA stays mostly the same throughout life, the way the body reads its DNA code is dynamic, thanks to epigenetic modifications: By tightly packing some sections of DNA and covering other parts of the molecule with chemical tags, these modifications change how a cell uses the DNA and, consequently, how the cell functions.

In the new study, scientists observed mice that were given a high-fat diet before switching back to a normal diet to return them to their starting weight. Once they dropped the extra weight, the mice were metabolically indistinguishable from mice that were never fed a fatty diet. However, when the researchers looked at the mice’s fat cells, they found that despite their weight loss, the cells still carried epigenetic changes that had arisen during the weight gain.

To check whether this also happens in humans, the team then analyzed cells from people who had undergone bariatric surgery. There, they found patterns of gene activity that suggested epigenetic changes took place and persisted after weight loss, said study co-author Laura Hinte, a doctoral student of nutrition and metabolic epigenetics at ETH Zurich.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Adipocytes [fat cells] are known to go through a kind of identity crisis in obesity — they kind of forget who they are and what they are supposed to be doing," Hinte told Live Science. This work showed those changes remained "long after the mice had lost weight," she said, and a similar identity shift might be happening in human fat cells, the data suggest.

Further evidence came from a closer look at the mice's fat cells. When removed from the formerly obese mice and bathed in glucose and palmitate — high-sugar and fatty ingredients — the fat cells enlarged more quickly than those taken from control mice. The formerly obese mice also gained weight more quickly when provided a high-calorie diet, compared with the controls.

"The epigenetic changes didn't have consequences for the mice as long as they were in a healthy environment," Hinte said, referencing when the mice were given a standard diet.

Other mechanisms are likely involved in weight rebound, Hinte added. For instance, it's "very likely" that this memory exists in other cell types in the body, such as neurons, where these modifications may affect appetite in people who have lost weight.

The study doesn't prove that epigenetic changes directly cause weight rebound. However, it strongly suggests that these mechanisms may play a role in the complex interplay of forces that drive obesity.

Dr. Fatima Cody Stanford, an associate professor of medicine and pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, who was not involved in the study, said it "offers valuable insights into why maintaining weight loss is challenging."

She noted, however, that the observations in lab mice "may not fully represent the complexity of human obesity." Another major caveat to this study is whether it has practical applications, she said. To date, scientists haven't found many molecules that can tweak the epigenetics of DNA in a cell's nucleus.

The work also "strengthens the argument for early intervention when it comes to both weight gain and weight regain," Saunders told Live Science.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Marianne is a freelance science journalist specializing in health, space, and tech. She particularly likes writing about obesity, neurology, and infectious diseases, but also loves digging into the business of science and tech. Marianne was previously a news editor at The Lancet and Nature Medicine and the U.K. science reporter for Business Insider. Before becoming a writer, Marianne was a scientist studying how the body fights infections from malaria parasites and gut bacteria.