Experimental menstrual product turns blood to jelly

Scientists are working to develop a new filler for period products that they say could help prevent leaks.

An experimental additive for menstrual products turns period blood into jelly.

The hope is that this additive could help prevent leaks while also reducing the risk of a dangerous condition called toxic shock syndrome, the researchers behind the product say.

The seaweed-derived material was unveiled in a study published Wednesday (July 10) in the journal Matter. Its developers believe the product could someday be used as an alternative filler in conventional pads or as a spill-proof lining to insert in menstrual cups. For now, though, the prototype has only been tested in early lab experiments.

"The way these products have worked for a long time is to absorb or retain menstrual fluid so that you can remove it later," said lead study author Bryan Hsu, a biomedical scientist at Virginia Tech. "But what if we could improve menstrual care by solidifying menstrual blood? If it's in a gel form, it's less likely to leak and spill."

Related: What causes spotting between periods?

A shortfall of conventional menstrual products is their risk of leaking. Even in developed nations, concerns around such leaks can contribute to children missing school during their periods; besides that, leaks are an inconvenience in that they can damage clothes.

One reason leaks can occur is because, unlike blood from a vein, menstrual blood doesn't usually coagulate. "There are a lot of fibrinolytic enzymes [in period blood] which break down blood clots, as well as clumps of tissue and cells," Hsu told Live Science. "It's fundamentally a different type of blood."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Hsu and his colleagues hypothesized that the right material could convert menstrual blood into a solid form that would be less likely to leak. Their solution: polysaccharides. These are chains of sugar molecules that thicken liquid solutions really well. Pectins, which are often used to thicken fruit preserves, and cornstarch are good examples of such molecules.

Using pig's blood modified to prevent clots, the team tested naturally derived sugars to see which could turn it into a gel-like form. Their tests included xanthan gum, a common food additive, as well as alginate and kappa carrageenan, which are derived from seaweed.

"The advantages of using biomaterials like these are that they're biocompatible," meaning they don't harm living human tissue, "and completely biodegradable," Hsu said. "Single-use, disposable menstrual products contribute a ton of waste, so if we can replace some of the less-biodegradable components, that will have a positive environmental impact."

The researchers measured the viscosity of blood mixed with each polysaccharide and found alginate to be the most promising candidate. According to Hsu, alginate's excellent gel-forming properties most likely stem from a phenomenon called calcium-mediated crosslinking.

Related: Menstrual cycle linked to structural changes across whole brain

"In water, the long sugar chains float around individually," Hsu explained. However, each alginate molecule also has a series of smaller chains, which contain so-called carboxylate groups, branching off it. Period blood contains charged calcium particles that grab hold of these small chains, forming bonds between alginate molecules. Together, these bonds create "an interlinked network" that locks everything together in a gel, Hsu said.

The team needed to ensure that powdered alginate was practical for use in menstrual products. They added a small amount of glycerol — a liquid that draws water to itself — to help draw blood through the dry powder.

They also incorporated an antibacterial substance to help prevent the growth of Staphylococcus aureus. This bacterium can cause toxic shock syndrome, a rare complication of some infections in which bacteria release dangerous toxins. A small percentage of cases are tied to tampons — typically highly absorbent tampons that have been left in for longer than recommended.

The antibacterial substance, derived from algae, curbed the growth of S. aureus at body temperature. The substance also didn't leach out of the powder, so the researchers think it's unlikely to disrupt the vaginal microbiome.

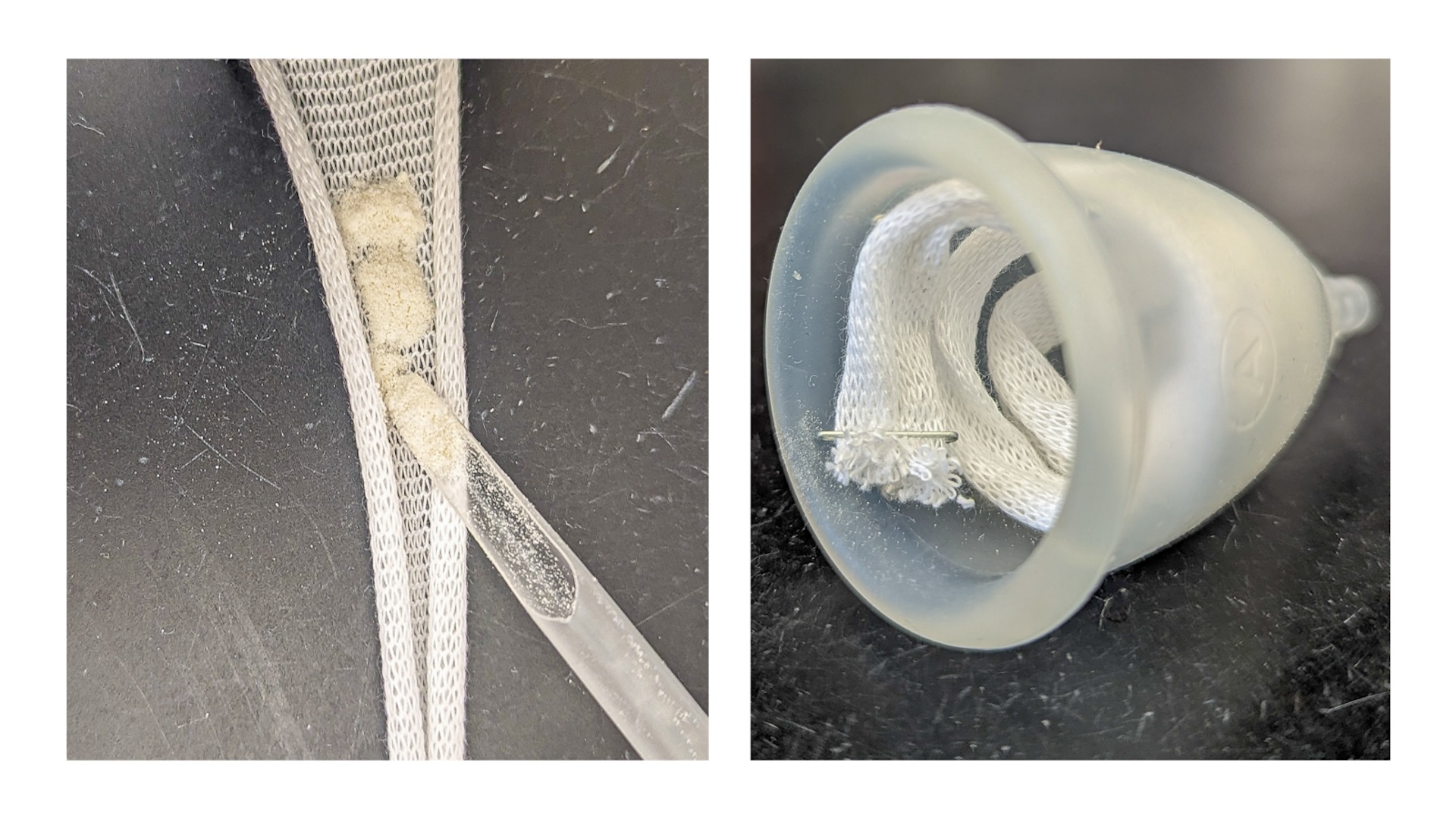

The researchers then created a prototype pad with their new filler and pitted it against conventional pads in laboratory tests. They measured how well the two products absorbed about 0.3 ounces (8 milliliters) of blood and then tested their ability to retain the fluid under pressure, as if someone were sitting on them.

"[The prototype] performed just as well as the commercial pad in terms of absorption, but importantly, our material retained that blood much better," Hsu said.

The team also tested the powder in a menstrual cup, by placing it in a cotton lining designed to sit inside the cup. In these tests, the alginate powder consistently reduced the amount of spillage that occurred when the cup was removed from a synthetic vagina.

"Even if you invert the cup, the blood doesn't flow out," Hsu said. "You remove the powder-containing cotton to empty out the blood. Hopefully this would make it easier to manage a cup when someone's out and about in a public space."

There's still a way to go before the team's product makes it to market. Safety testing and manufacturing processes need to be addressed for the additive to pass regulatory muster. But Hsu hopes that, eventually, this will make a difference to the lives of people who menstruate.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Victoria Atkinson is a freelance science journalist, specializing in chemistry and its interface with the natural and human-made worlds. Currently based in York (UK), she formerly worked as a science content developer at the University of Oxford, and later as a member of the Chemistry World editorial team. Since becoming a freelancer, Victoria has expanded her focus to explore topics from across the sciences and has also worked with Chemistry Review, Neon Squid Publishing and the Open University, amongst others. She has a DPhil in organic chemistry from the University of Oxford.

Man gets sperm-making stem cell transplant in first-of-its-kind procedure

'Love hormone' oxytocin can pause pregnancy, animal study finds