Man gets sperm-making stem cell transplant in first-of-its-kind procedure

A man in his early 20s received a transplant of his own sperm-producing stem cells, which had been frozen since his childhood, in an attempt to regain fertility. Doctors are waiting to see if the treatment works.

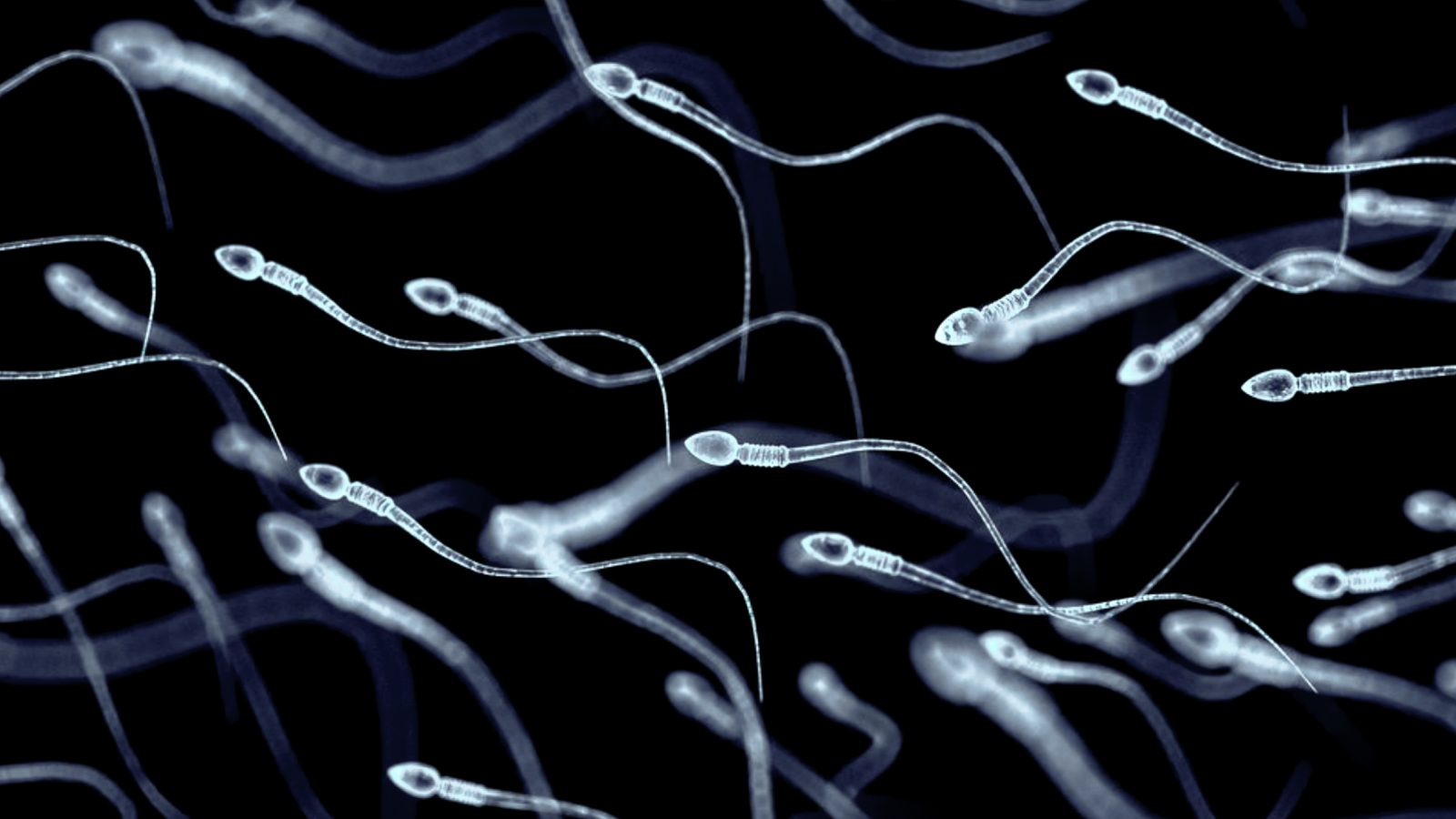

In the United States, an estimated 645,000 men ages 20 to 50 have azoospermia, a condition in which no sperm are present in their ejaculate. Now, scientists are testing a potential treatment: transplanting sperm-forming stem cells into the reproductive system.

"If refined and proven safe, spermatogonial stem cell (SSC) transplantation could be a revolutionary fertility-restoring technique for men who've lost the ability to produce sperm," Dr. Justin Houman, an assistant professor of urology at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email.

It could be especially helpful for "cancer survivors treated before puberty or men with genetic or acquired testicular failure," he added.

So what does this experimental treatment involve?

Related: Sperm cells carry traces of childhood stress, epigenetic study finds

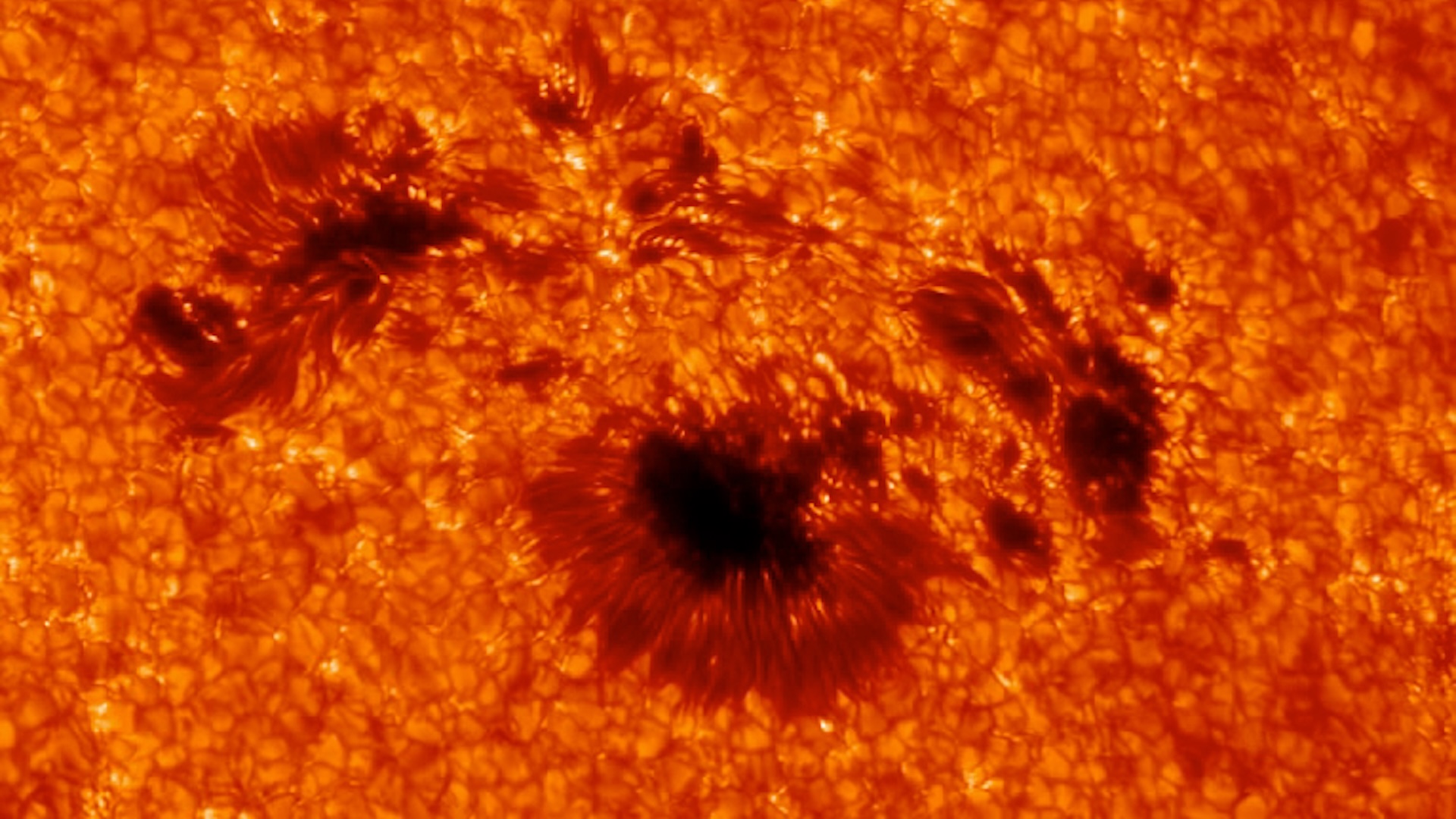

Sperm-forming stem cells are at the core of the therapy. These cells, found in the testicles even before puberty, typically mature into sperm when testosterone levels rise during adolescence.

But medical conditions — like a blockage in the reproductive tract or certain genetic mutations or hormonal problems — and treatments such as chemotherapy can damage these stem cells or block their development into sperm, thus leading to infertility.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

If a young patient wishes to preserve their sperm-forming stem cells for future use, doctors can use an ultrasound-guided needle to collect the stem cells into the rete testis — a network of small tubes that connects to the seminiferous tubules, where sperm are typically produced. The needle is carefully inserted into these tubes through the base of the scrotum, and once collected, the stem cells are frozen.

Later on, doctors can then reintroduce the preserved stem cells into the rete testis, using a similar, ultrasound-guided technique. The goal is for the cells to implant in the seminiferous tubules, where they can mature and begin producing sperm, mimicking the natural process that occurs during puberty.

This procedure has previously been tested in animals, and it successfully enabled male mice and monkeys to produce sperm and father offspring.

Now, researchers have documented the technique's first use in humans. According to a paper published March 26 on preprint server medRxiv, a man in his early 20s has now received a transplant of his own, once-frozen stem cells. He had his sperm-forming stem cells preserved as a child, before he underwent chemotherapy for bone cancer.

If the stem-cell transplant is successful, the man's body should begin producing sperm, which was not possible before the procedure due to azoospermia. So far, ultrasounds have confirmed that the transplantation procedure didn't damage the patient's testicular tissue, and his hormone levels are normal.

No sperm have been detected in his semen yet, but the researchers are continuing to analyze his semen twice a year to see if the reproductive cells show up.

One possible reason for the lack of detectable sperm, according to the researchers, is that only a small quantity of stem cells were collected in the patient's childhood, to minimize harm to his tissues. That means the number of preserved and transplanted cells capable of developing into sperm remains low. As a result, sperm production may be limited.

Related: 100 million-year-old sperm is the oldest ever found. And it's giant.

If sperm do not ever appear in the patient's ejaculate but the patient wants to father children, doctors could attempt to recover, via surgery, any small amount of sperm made by the stem cells.

Dr. Laura Gemmell, a reproductive and endocrinology fellow at the Columbia University Fertility Center, suggested another alternative: a technique called the Sperm Tracking and Recovery (STAR) System. This is a machine developed at the Columbia University Fertility Center that combines artificial intelligence technology, robotics, and microfluidics, a technology that uses tiny channels to analyze fluid within a device. This tech identifies and recovers extremely scarce sperm cells from an ejaculate, she told Live Science in an email.

It takes only one sperm to conceive a child, Gemmel noted. "If we can find that sperm noninvasively, we can inject that single sperm into an egg and make an embryo," Gemmel said.

She added that, "our field has seen success with ovarian cryopreservation and retransplantation in young girls with childhood cancers. I'm hopeful that in the future, we can provide an option for young boys who want to one day father a biologic child."

As with all medical procedures, sperm stem cell transplants come with some risks.

For example, there's a chance that a fraction of the transplanted stem cells have cancer-causing genetic mutations and could someday develop into a tumor, especially in patients who've had leukemia in the past, Houman said. And even though the procedure uses the patient's own cells, there's a "theoretical risk" that the immune system could still react and trigger inflammation, he said.

There are also ethical concerns around freezing the sperm stem cells from young boys — namely, how can doctors be sure the children can fully consent to the procedure, and that they have clear expectations around the long-term storage of their cells?

"We need to proceed cautiously, and with rigorous oversight," he said. "This is promising science — but it's still early days."

Editor's note: This story was updated on April 7, 2025, to correct the spelling of Dr. Laura Gemmell's name.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Clarissa Brincat is a freelance writer specializing in health and medical research. After completing an MSc in chemistry, she realized she would rather write about science than do it. She learned how to edit scientific papers in a stint as a chemistry copyeditor, before moving on to a medical writer role at a healthcare company. Writing for doctors and experts has its rewards, but Clarissa wanted to communicate with a wider audience, which naturally led her to freelance health and science writing. Her work has also appeared in Medscape, HealthCentral and Medical News Today.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.