New mRNA injection is step forward in 'quest' to find preeclampsia cure

A new mRNA therapy tested in mice may target the root cause of the potentially fatal pregnancy disorder preeclampsia. It's yet to be tested in humans.

An mRNA therapy could treat the potentially deadly pregnancy disorder preeclampsia, which currently has no cure, a new study in rodents finds.

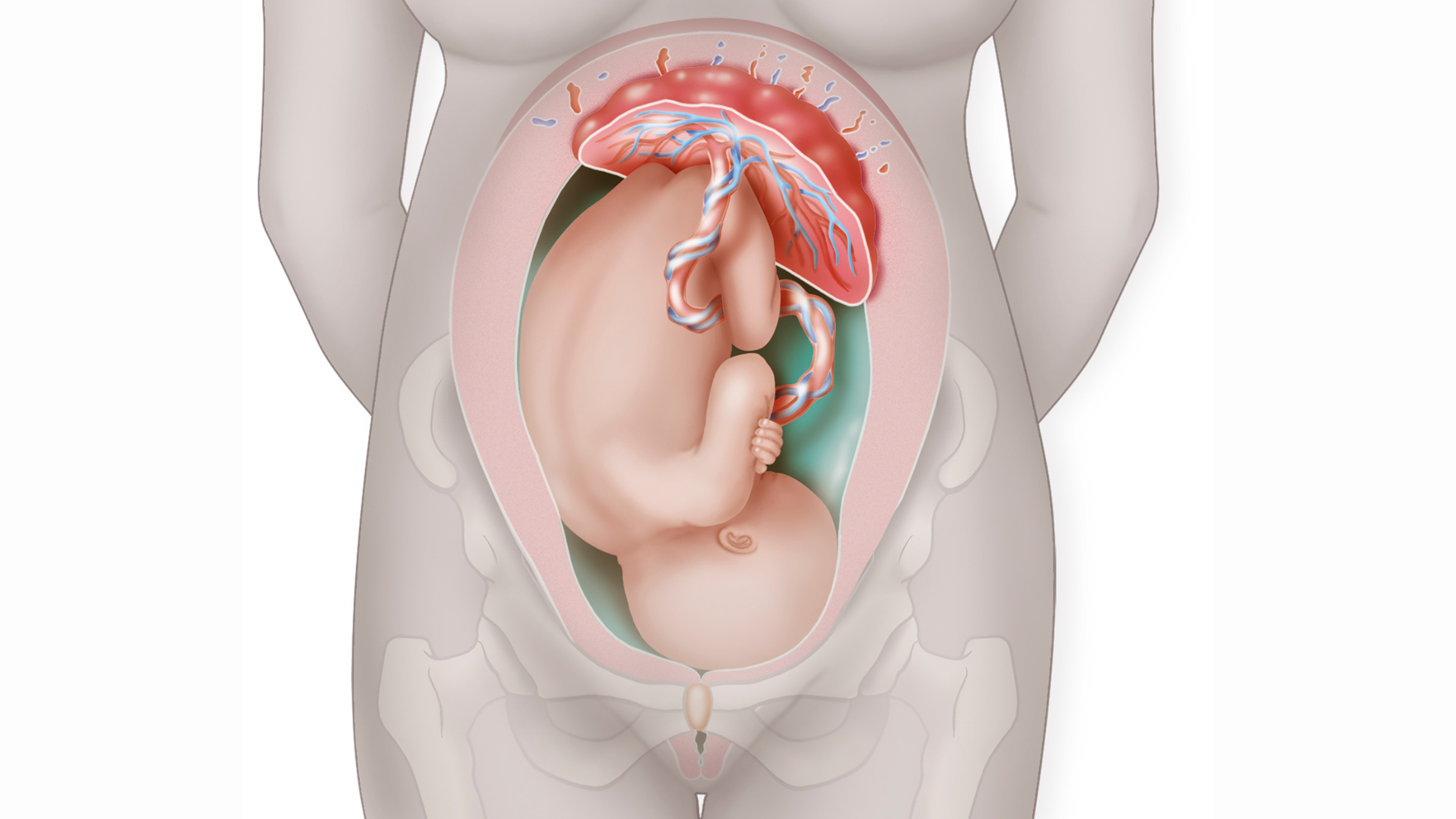

In preeclampsia, pregnant people develop persistently high blood pressure that can lead to organ damage, causing protein to appear in the urine and sometimes organ failure. The condition affects between 3% and 5% of pregnancies, usually around 20 weeks after conception, although it can also occur after birth. Preeclampsia is responsible for more than 70,000 maternal deaths and 500,000 fetal deaths worldwide each year.

There are currently no drugs that slow the progression of preeclampsia. The only way to cure the condition is to deliver the baby. Until then, the mother's symptoms can be managed using drugs that lower blood pressure.

To find a potential solution, the researchers created an experimental therapy for preeclampsia that harnesses the same technology found in the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines. The therapy uses tiny, spherical particles to deliver a type of genetic material known as messenger RNA (mRNA) to cells. This mRNA acts as a blueprint for the cells to make specific proteins.

Related: 'Mini placentas' may reveal roots of pregnancy disorders like preeclampsia

In the case of the COVID-19 vaccines, the resulting proteins train the immune system to make antibodies to thwart future COVID infections. For the preeclampsia treatment, the mRNA instead instructs cells of the placenta to make more vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).

During a healthy pregnancy, VEGF helps promote the formation of blood vessels in the placenta, which enables more blood — and the nutrients and oxygen within it — to flow to the growing fetus. However, for unknown reasons, the placenta in patients with preeclampsia doesn't develop properly, restricting blood flow across it and hindering the fetus's growth.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The condition also causes placental cells to release toxins that inhibit VEGF, which ultimately damages cells that line the mother's blood vessels and raises their blood pressure.

In the new study, published Wednesday (Dec. 11) in the journal Nature, researchers tested the new mRNA therapy in pregnant mice that had a condition similar to preeclampsia.

Just one injection of the therapy, delivered halfway through the mice's pregnancy, lowered their blood pressure to a healthy level until they gave birth. The rodents' newborns were also heavier than those of mice that weren't injected with the mRNA. The placental blood vessels of the treated mice had been partially restored, which made their symptoms less severe.

In a commentary on the new research, Dr. Ravi Thadhani, executive vice president for health affairs at Emory University in Georgia, and Dr. S. Ananth Karumanchi, a professor of medicine at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in California, said that the researchers have "advanced the quest to develop a safe and effective therapy for women with preeclampsia."

However, Thadhani and Karumanchi, neither of whom were involved in the research, added that the results "still raise questions" about the suitability of this therapy for preeclampsia. While the inhibition of VEGF in preeclampsia is a problem, having excessive amounts of the protein in the uterine lining has been linked to pregnancy loss in mice, they said. So the new mRNA may need to strike just the right balance of VEGF.

The study team now plans to test whether the new therapy is safe and effective in larger animals — namely, non-human primates. This level of investigation is necessary for the therapy to someday be given to human patients.

"There's a lot of work to be done really making sure this is a safe technology as we work to scale this up," study lead author Kelsey Swingle, a doctoral candidate at the University of Pennsylvania, told Live Science.

One of the things the team needs to decipher is how often and when the therapy should be given to pregnant people. This is a tricky question to answer currently, considering that the average length of a mouse pregnancy is around 20 days, compared with approximately 40 weeks in humans.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30. (emily.cooke@futurenet.com)

Man gets sperm-making stem cell transplant in first-of-its-kind procedure

'Love hormone' oxytocin can pause pregnancy, animal study finds