The gut 'remodels' itself during pregnancy, study finds

The inner lining of the small intestine nearly doubles in size during pregnancy and breastfeeding, according to new research in mice and human tissue.

During pregnancy, the breasts expand, resting heart rate speeds up, and organs shift to accommodate the growing fetus. And now, scientists have added one more item to this list: the gut grows dramatically.

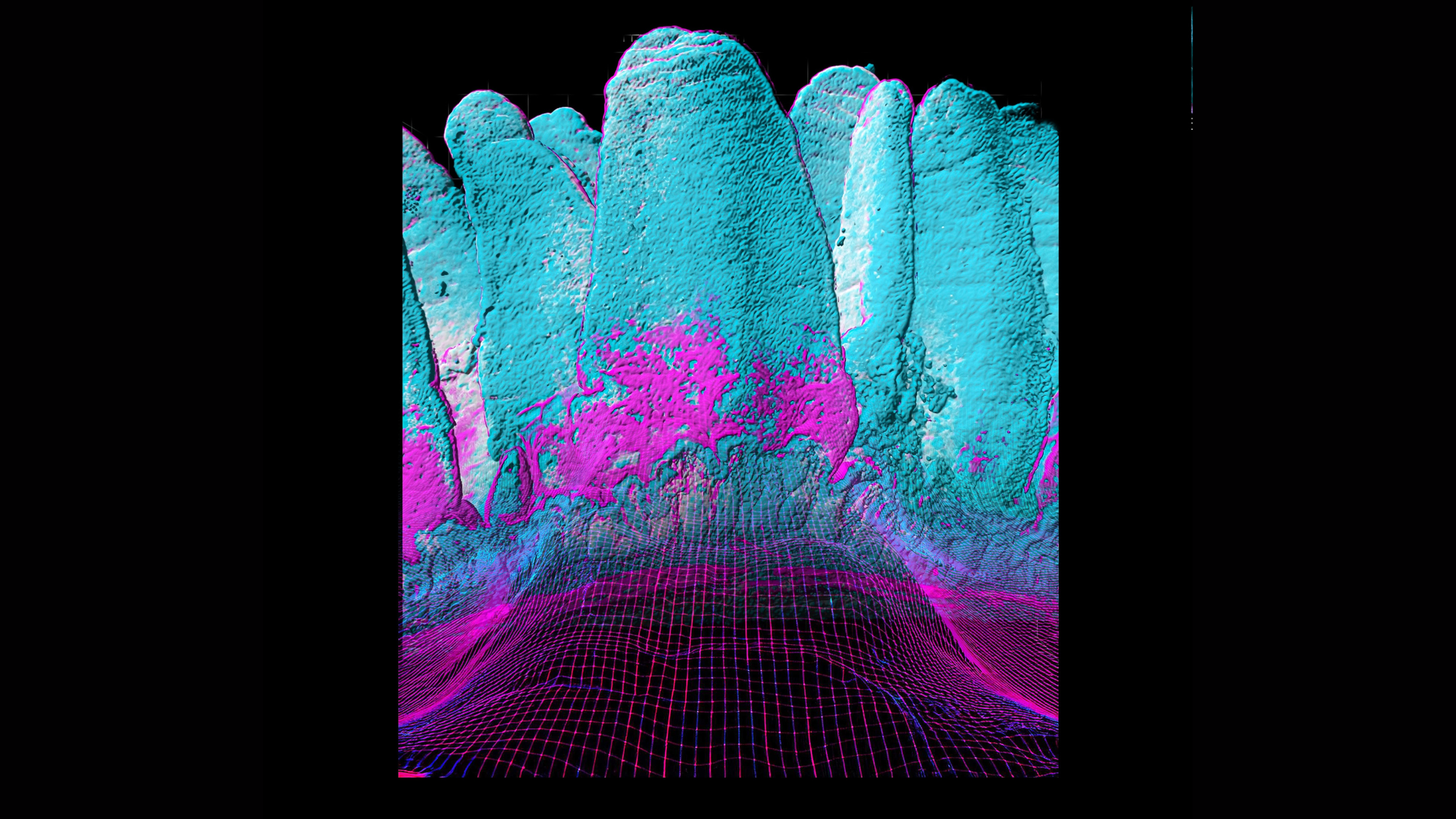

According to new research conducted in mice and 3D models of human tissue, the lining of the inside of the small intestine — known as the epithelium — changes its structure and doubles in size during pregnancy, as well as during breastfeeding.

Amid these pivotal stages of reproduction, mothers have to eat more nutrients to support the growth and development of their baby. The team behind the new research speculate that these gut changes may also enable mothers to absorb more nutrients from the food they do eat and thus channel even more toward their babies. This idea has yet to be confirmed, though.

The scientists described their new findings in a paper published Dec. 4 in the journal Nature.

Related: New mRNA injection is step forward in 'quest' to find preeclampsia cure

"Our team has discovered an amazing new way how mother’s bodies change to keep babies healthy," study co-author Josef Penninger, a scientific director at the Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research in Germany, said in a statement.

The team made this discovery after studying the role of a signaling molecule, called RANK, which can be found in numerous tissues around the body. This molecule has previously been shown to control the formation of the milk-producing mammary glands in the breasts. Hormones involved in reproduction, such as progesterone, also ramp up RANK production within these glands, suggesting the molecule helps orchestrate body changes associated with pregnancy.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Beyond breast tissue, RANK is also found in the intestinal epithelium — but until now, little was known about its role there.

In the new study, Penninger and colleagues used stem cells to grow small, 3D replicas of the human and mouse small intestine. They grew these "organoids" with the help of specialized chemicals. They then exposed the cells within the mini-intestines to RANK, which triggered several structural changes.

Namely, tiny, finger-like projections that protrude from epithelial cells suddenly elongated and flattened out. These projections, known as villi, help increase the surface area of the gut, boosting nutrient absorption through the tissue.

A similar thing happened in pregnant and breastfeeding mice, the team found. However, without RANK, these changes didn't occur. In separate experiments in which they genetically modified mice to not produce RANK, the intestines stayed the same.

What's more, the milk produced by breastfeeding mice who lacked RANK contained fewer nutrients than that from RANK-producing mice, and the former mice birthed offspring that were underweight in comparison.

Taken together, these findings suggest that the intestinal epithelium remodels during reproduction to maximize nutrient absorption for the developing baby, the team theorized.

"These new studies provide for the first time a molecular and structural explanation of how and why the intestine changes to adapt to enhanced nutrient demand of mothers," Penninger said.

Going forward, the team plans to investigate whether this tissue remodelling also occurs in humans, as well as explore whether factors other than RANK also control the process.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30. (emily.cooke@futurenet.com)

Man gets sperm-making stem cell transplant in first-of-its-kind procedure

'Love hormone' oxytocin can pause pregnancy, animal study finds