Astronauts could ditch diapers on spacewalks thanks to new device that let's them drink their pee

A new device may someday soon allow astronauts to drink purified water made from their filtered pee during spacewalks.

Venturing outside of the International Space Station (ISS) is challenging enough without having to worry about nature calling in the middle of your spacewalk — now, scientists say they've devised a new way to capture astronauts' pee and recycle it into drinkable water within minutes.

For years, astronauts on spacewalks around the ISS have relieved themselves using a disposable diaper inside their spacesuit, known as a maximum absorbency garment (MAG). These garments, first designed in the early 1980s, collect and store urine, enabling astronauts to "go" on the go. But given spacewalks can sometimes take up to eight hours, MAGs can leave astronauts physically uncomfortable and at risk of skin irritation and infection.

MAGs also don't recycle the water in urine, so while on their walk, astronauts must rely on a fixed supply of 0.2 gallons (0.95 liters) of water that they carry in an in-suit drink bag.

But now, scientists think they have a solution to this problem: a new, lightweight system that can collect and purify around 1.69 fluid ounces (500 milliliters) of water from urine within a person's spacesuit and in just five minutes.

Related: Circus 'Wall of Death' stunt may keep astronauts fit on the moon

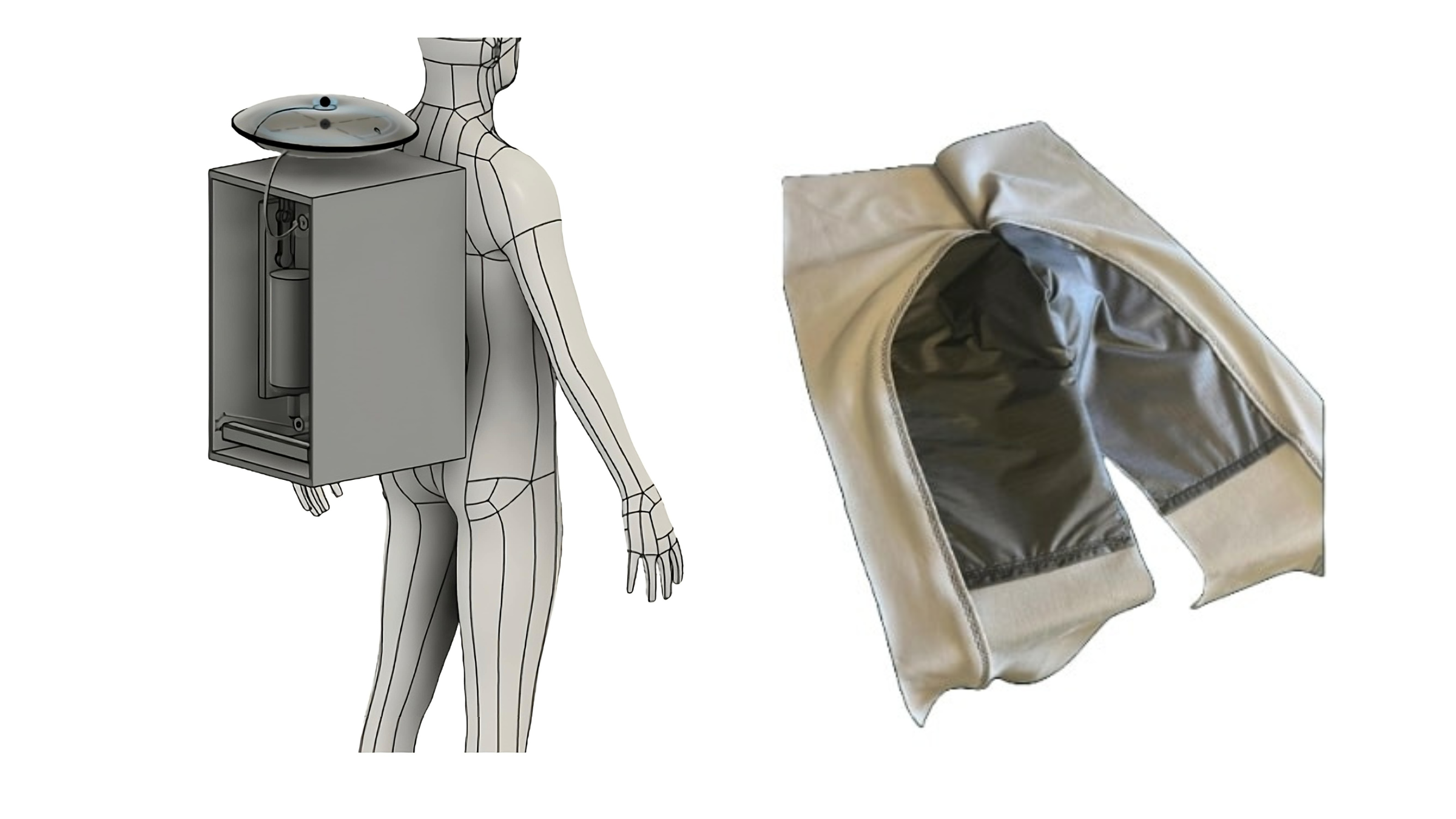

If implemented, the system would involve astronauts wearing an undergarment that's made from a flexible compression material and lined with antimicrobial fabric. The system also includes a humidity sensor that senses urine; the sensor sits within a silicone cup beneath the wearer's genitalia.

The detection of pee switches on a vacuum pump that then draws the urine up into a filtration device carried on the astronaut's back. The filter measures about 15 inches (38 centimeters) tall and 9 inches (23 cm) wide. Within the 17.6-pound (8 kilogram) filtration device, urine would be transformed into fresh water that could subsequently be delivered into the spacesuit's drink bag.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The new system is still in its initial testing stage. However, if it makes it through development, it could help solve a dilemma for astronauts engaging in space exploration, the team who developed the system say. The issue of how to deal with urine on spacewalks is particularly relevant considering that NASA plans to establish a permanent outpost on the moon by the end of the decade.

The team described their new device in a paper published Friday (July 12) in the journal Frontiers in Space Technology. So far, in the lab, the device has been shown to effectively remove the major components of urine and reduce its salt levels to meet health standards, the team says.

"Getting urine away from the body as quickly as possible should reduce some of the health complications that astronauts are currently experiencing like rashes, urinary tract infections, and digestive distress," Sofia Etlin, the lead study author and a researcher at Weill Cornell Medicine, told Live Science in an email.

"Second, the greater overall supply of water that our system generates will keep the astronauts hydrated," Etlin added.

Spacesuits are limited in their size and battery capacity, so the bulk and energy requirements of the new system would need to be carefully considered. However, improving astronauts' health and performance and supplying them enough water for emergencies is a worthy trade-off, the authors wrote in the paper.

"When it comes to sending new technology to space, the process is quite time intensive," Etlin said. The team has tested the filtration system, "but further study with humans will be required to maximize fit and comfort."

The team also needs to check that the device works under conditions realistically found in space, such as microgravity. If successful in tests on Earth, the spacesuit would then be trialed during real spacewalks from the ISS.

"Our system would likely only be implemented into new spacesuits according to their specifications, which would require some further tailoring of the technology," Etlin said. "So we'll definitely not see astronauts diaper-free next year, but you can never tell what the future holds."

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30. (emily.cooke@futurenet.com)