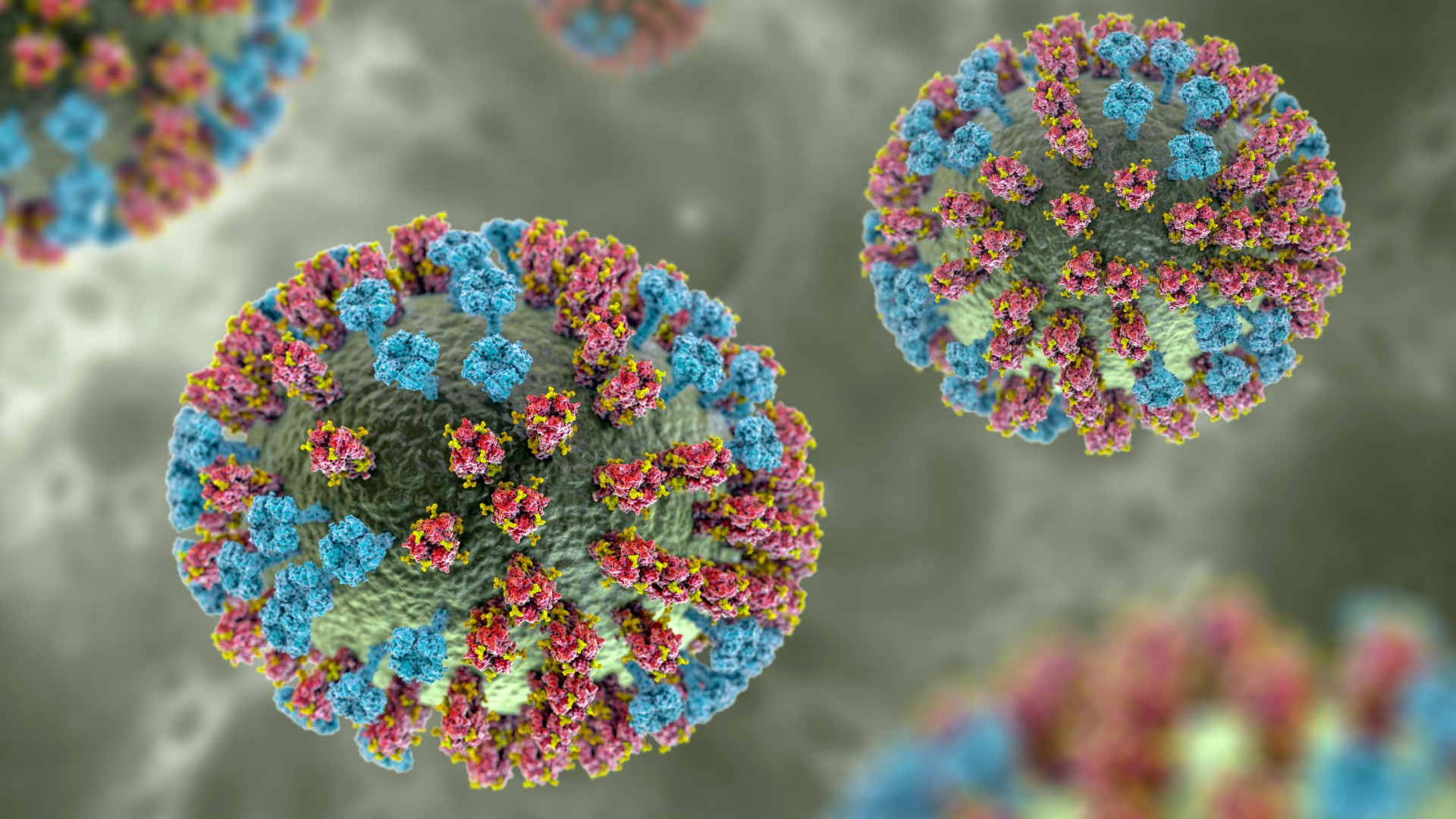

A single gene mutation could enable H5N1 to spread between people, study finds

A new laboratory study pinpoints a way H5N1 bird flu could evolve to spread from person to person.

Dozens of people in the United States have caught bird flu from animals this year, but there's no evidence that the viral disease has spread from one person to another. However, a single mutation in the virus could make human-to-human spread possible, a new study finds.

This genetic change would make the virus a much better "match" for cells in humans' airways; it would enable a protein on the surface of the virus to fit snugly into a receptor found on human cells. That would allow the virus to infect those cells more easily — and make it more likely to spark a pandemic.

"In order to get sufficient infection, the virus needs to very efficiently attach to the cells in the airway," said Jim Paulson, a biochemist at The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California, and co-senior author of the study. "In fact, it's believed that transmission [between people] cannot occur until the virus has acquired the human-type receptor specificity."

Currently, the circulating bird flu virus — called H5N1 — is a much better match for bird receptors. The new study, published Thursday (Dec. 5) in the journal Science, essentially explored what it would take for the virus to switch its preference to people.

Related: How to avoid bird flu

Pandemic potential

As of Dec. 4, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has confirmed 58 H5N1 infections among people in the U.S. The virus has also been circulating among wild birds, poultry and cattle in the country. Most of the confirmed human infections — about 60% — have been linked to exposure to infected cattle, while 36% have been associated with birds. The two remaining infections have no known source, but they're also suspected to have originated in animals.

So far, the human cases in the U.S. have been mild, triggering eye redness or a cough, at most. However, a teen infected in Canada has had more severe symptoms, and historically, H5N1 infections have been deadly in hundreds of cases. So there's a concern that the strain circulating in the U.S. could evolve to become deadlier, more transmissible, or both.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But how is H5N1 infecting people now, if it's not a good match for humans? "When the virus is coming from an infected animal, like birds or from cows, it's a very high concentration of virus," Paulson told Live Science. So, even if the virus is not a perfect match, the sheer number of viral particles entering the person's body can still lead to infection, he said.

To then jump to another person, though, the virus would need to be a better match. That's because, when a respiratory virus spreads between people, it's typically passed in tiny droplets expelled from the infected person's mouth. These droplets carry a relatively low concentration of virus.

Related: Bird flu strikes 1st child in the US — CDC says infection source unknown

To probe how H5N1 might become a good match, the researchers looked at the genetic code of the virus that infected the first person ever known to catch bird flu from a cow. They zeroed in on the code for hemagglutinin (HA), a protein the virus needs to infect cells.

"What we're looking at is a protein that comes from a virus, but it's isolated," said co-senior author Ian Wilson, a structural biologist at Scripps. The team didn't work with whole viruses in the lab, he clarified.

When the researchers looked at how well the isolated HA protein plugged into bird receptors compared with human ones, they found that the existing version had "strong avian-type specificity." They then introduced mutations, triggering changes in the part of HA that directly interacts with receptors.

They found that a single mutation — called the Gln226Leu substitution — can "completely switch" the virus's preference, making it a match for humans instead of birds. The mutant virus still didn't bind to human cells quite as well as it had to bird cells, but the switch in its preference was "nevertheless clear and pronounced" across different tests. Adding a second mutation — Asn224Lys — did tighten the virus's grip, though.

That Gln226Leu mutation had been flagged in previous studies of H5N1, which also hinted that it could boost the virus's ability to infect humans. However, most previous studies found that the HA would need multiple mutations to completely switch its preference, the researchers noted in their report. In this case, it seems just one mutation is sufficient.

The switch to human receptors is a major factor that could give an animal virus the potential to spark a human pandemic, the authors noted. For that reason, scientists should look out for the Gln226Leu mutation as they continue to track the spread of H5N1, the study suggests.

Related: H5N1 bird flu is evolving to better infect mammals, CDC study suggests

For now, "the particular mutation that we're reporting in this paper has not yet been reported in a database," Wilson said. The recent Canadian case may have some notable mutations in the HA protein, at least according to informal discussions among scientists on social media, Paulson said. For now, though, "it's a little premature to talk about that particular case," he added.

Ultimately, more human H5N1 infections would make the Gln226Leu mutation more likely to crop up. "The more people that get infected, the more likelihood is that … that mutation will get selected for," Wilson told Live Science. "When there's very few people infected, there's less likelihood of that mutation coming up."

The study didn't consider all of the factors that could give H5N1 pandemic potential. A second viral protein, called neuraminidase, also plays an important role, as does the pH that the virus needs to fuse to and get inside cells. With the Northern Hemisphere's flu season ramping up, there's a possibility that H5N1 could infect a person who is already infected with seasonal flu. From there, those two viruses could swap genes, thus opening the door for H5N1 to pick up genes that might help it adapt to humans.

"Genes from the previous human virus — they're already adapted to humans," Paulson said. "Therefore, the mutation of the hemagglutinin becomes a key factor in the success of the virus."

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.