How do people die of the flu?

Severe flu infections can lead to a range of deadly complications, especially in people whose immune systems are compromised by age or disease.

Each flu season, about 8% of people in the United States get sick with influenza. Most recover from the sickness, but thousands die annually of seasonal flu. In the last decade, there have been between 21,000 and 51,000 deaths from flu each season, with the exception of 2020-2021 when flu activity was unusually low.

Certain groups are most likely to develop severe flu infections that could lead to death: children under 5, adults 65 and older, people with chronic health conditions and pregnant people.

But how do people actually die of the flu?

There are many ways people can die of the flu. Influenza viruses can inflict serious damage on a range of organs and systems throughout the body, including the lungs, heart, brain and overall immune system, said Dr. Akiko Iwasaki, a professor of immunobiology and molecular, cellular, and developmental biology at Yale University and investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Related: How long is the flu contagious?

These life-threatening complications include pneumonia, which inflames the air sacs of the lungs and can cause them to fill with pus. Flu viruses can directly invade the lungs, causing what's called viral pneumonia. In addition, by damaging cells that line the respiratory tract, the viruses can open the door for bacteria in the body to overgrow, driving inflammation and possibly bacterial pneumonia.

"These are the bacteria that commonly colonize the upper respiratory tract of people without causing any disease," Iwasaki said. After someone gets the flu, these bacteria can gain a foothold in the lungs and multiply.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

That's partly because flu viruses make the cells lining the respiratory tract more vulnerable to bacterial penetration and infection, and then "bacteria can proliferate and cause damage more easily," Dr. Octavio Ramilo, chair of the Department of Infectious Diseases at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, told Live Science.

Severe pneumonia can also cause acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), in which the lungs accumulate fluid, become stiff and can't expand well.

Flu complications don't only affect the lungs, but also the heart. Myocarditis and acute pericarditis respectively inflame the heart's muscles and the sac that surrounds the organ. These conditions can affect the heart's ability to pump blood and disrupt its rhythm, sometimes with deadly consequences.

Flu infections can spark myocarditis because flu viruses inflame and damage the cells that line blood vessels, Ramilo said. The exact cause for pericarditis is unclear, but the tissue typically becomes inflamed following a viral infection like the flu.

Related: Could we ever eradicate the flu?

In rare cases, the flu can also lead to encephalitis, or swelling of the brain. This condition, which is estimated to occur in about 4 in 100,000 children in the U.S. each year, can lead to serious complications including convulsions, coma and death.

Scientists don't know exactly how the flu leads to encephalitis, but a leading hypothesis suggests the infection causes the body to release a flood of cytokines, which are molecules that cause inflammation. These molecules can then enter the brain because the organ's protective barrier has been compromised, potentially by the cytokines themselves. However, more studies are needed to confirm that theory.

Influenza can also lead to sepsis, a life-threatening, body-wide immune response. Flu viruses can trigger this immune reaction on their own, but they can also enable bacteria to enter the bloodstream by breaking down tissues in the body, Ramilo noted. Those bloodborne bacteria can then trigger sepsis. Some studies suggest influenza-associated pneumonia may raise the risk of sepsis up to sixfold, compared to a flu infection without pneumonia; that said, this complication is relatively uncommon overall.

Who is at highest risk of dying from the flu?

A major reason why older adults, young children, people with chronic medical conditions and pregnant people are vulnerable to deadly flu complications is the state of their immune systems.

Older adults experience senescence — essentially biological aging that leads to a decline in cell function that hinders the immune system, Ramilo said. In pregnant people, the immune system lowers its defenses so as not to attack the growing fetus. Thus, people become more vulnerable to flu-related complications during pregnancy, he explained.

Young children's immune systems haven't encountered many germs before. "The immune responses to the [flu] virus have to be developed from scratch," Iwasaki said. Because a child's immune system has no memory of flu viruses, "the virus has the chance to multiply before the immune responses can catch up," she said.

Chronic conditions — such as asthma, kidney disease, HIV/AIDS and cancer — raise the risk of flu complications by compromising either the immune or respiratory system, or both. The flu can also worsen chronic conditions, increasing the risk of death from other causes.

Thankfully, flu vaccines can help prevent severe flu infections and their potentially deadly knock-on effects. For people who do develop severe flu infections, treatments like Tamiflu can dramatically lower the risk of death if provided quickly.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

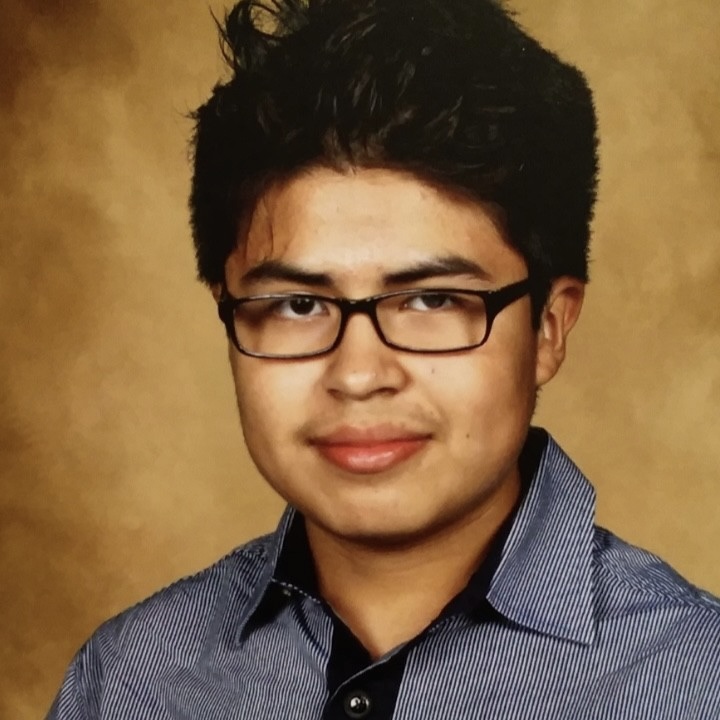

Bryan Rocha holds a bachelor's degree in sociology and a master's degree in global media and cultures, specializing in Spanish-speaking media. While at university, he won awards for his writing, helping him obtain the recognition of academic excellence in sociology. He is currently interested in writing articles focused on science and health and becoming a full-fledged science writer one day. In his free time, he enjoys reading Russian literature and learning to read and write in Mandarin.