50,000 'knots' scattered throughout our DNA control gene activity

The mapping of 50,000 mysterious "knots" in the human genome may someday lead to the development of new cancer drugs, researchers say.

Scientists have mapped tens of thousands of mysterious "knots" in human DNA, and they may play a key role in controlling gene activity.

Knowing the exact locations of these knots — known as "i-motifs" — could lead to the development of new treatments for diseases, including cancer, according to the researchers behind the work.

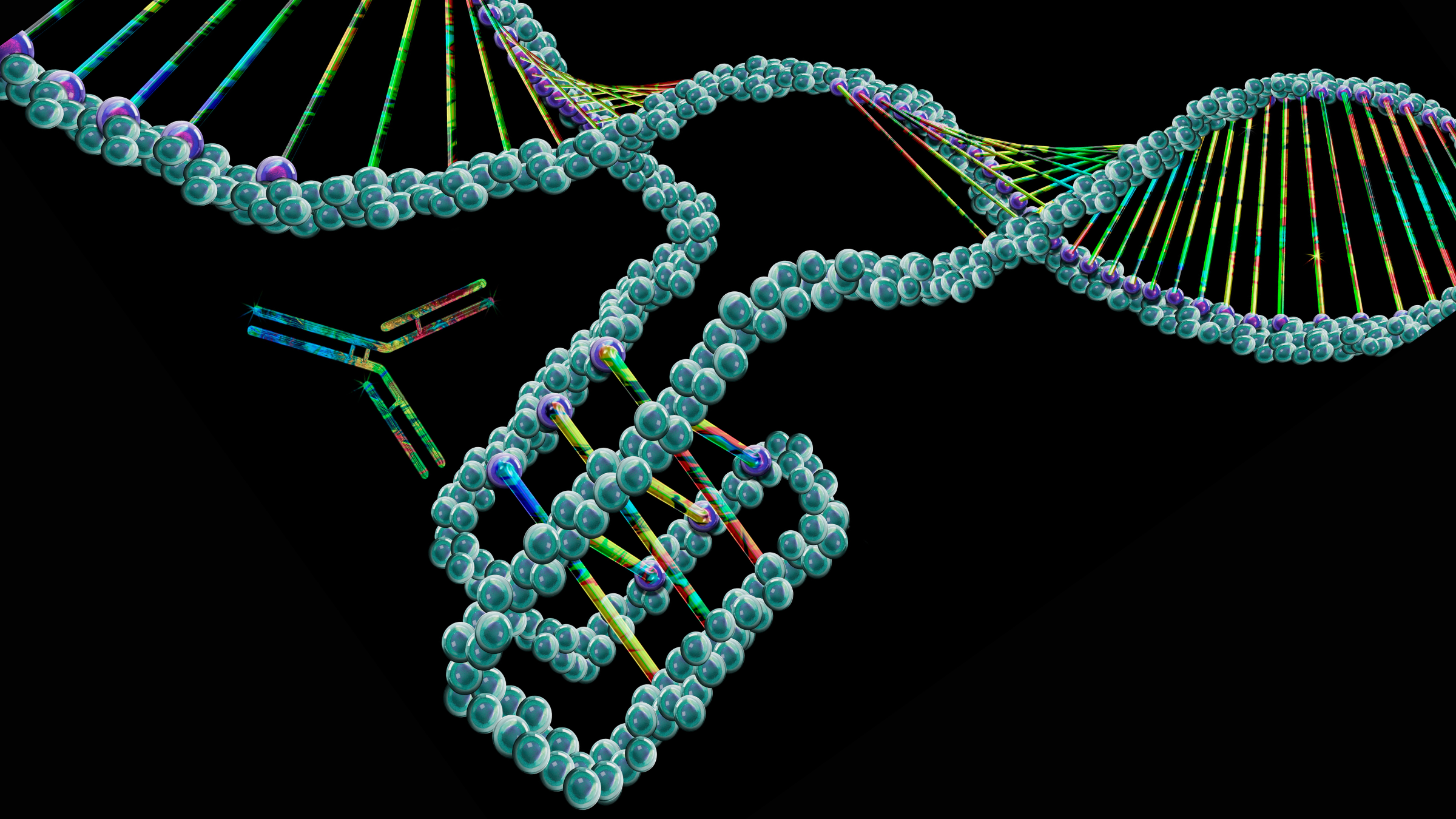

DNA is composed of building blocks called nucleotides, each of which carries one of the following bases: adenine, guanine, thymine or cytosine. These bases are the individual letters that make up DNA's code. DNA has a ladder-like structure, and normally, bases on one side of the ladder pair with a partner on the other side, linking up in the middle to form the ladder's rungs. Adenine pairs with thymine, while guanine pairs with cytosine.

However, sometimes, cytosines can pair with each other, rather than with guanine. This causes a DNA molecule to twist in on itself, creating a four-stranded, protruding structure called an i-motif.

Related: Rosalind Franklin knew DNA was a helix before Watson and Crick, unpublished material reveals

Researchers first discovered i-motifs in human cells in 2018. At the time, they suspected these knots could be important regulators of the genome, helping to control which genes are on or off. However, until now, little has been known about exactly where these knot-like structures are found and how many of them there are in the human genome.

In a new study, published Aug. 29 in The EMBO Journal, researchers mapped 50,000 i-motifs. These i-motifs are located throughout the genome, but they are commonly found in stretches of DNA that control gene activity, the study authors noted.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Our findings confirm that i-motifs are not just laboratory curiosities but widespread — and likely to play key roles in genomic function," Daniel Christ, study co-author and director of the Centre for Targeted Therapy at the Garvan Institute of Medical Research in Australia, said in a statement.

Christ and colleagues located the i-motifs within DNA that had been extracted from human cells in the lab. They pinpointed these knots using antibodies designed to specifically recognize and form complexes with the i-motifs. The team then purified these complexes of antibodies and knots in order to sequence the DNA within them.

"We discovered that i-motifs are associated with genes that are highly active during specific times in the cell cycle," Cristian David Peña Martinez, lead study author and a research assistant at Garvan, said in the statement. The cell cycle is the process by which cells replicate in the body.

"This suggests they [i-motifs] play a dynamic role in regulating gene activity," Peña Martinez added.

The team also found i-motifs within the "promoter" regions of various genes associated with cancer. Promoters are a type of genetic material that switches a given gene on and off, akin to a light switch. In cancerous cells, these genes can become dysregulated, driving the increased cell division and growth characteristic of tumors.

This new discovery hints that i-motifs could one day become a target for cancer-related drugs, the team proposed. They found i-motifs in the MYC gene family, whose activity is known to be dysregulated in around 70% of human cancers.

"This presents an exciting opportunity to target disease-linked genes through the i-motif structure," Peña Martinez said. Of course, more research is needed to move this idea from theory to application in human cancer patients.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30.