Papua New Guineans, genetically isolated for 50,000 years, carry Denisovan genes that help their immune system, study suggests

Genes inherited from Denisovans, extinct human relatives, may help Papua New Guineans in the lowlands fight off infection, while mutations to red blood cells may help highlanders live at altitude.

Papua New Guineans, who have been genetically isolated for millennia, carry unique genes that helped them fight off infection — and some of those genes come from our extinct human cousins, the Denisovans.

The research also found that highlanders and lowlanders evolved different mutations to help them adapt to their wildly different environments.

"New Guineans are unique as they have been isolated since they settled in New Guinea more than 50,000 years ago," co-senior study author François-Xavier Ricaut, a biological anthropologist at the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS), told Live Science in an email.

Not only is the predominantly mountainous terrain of the island country particularly challenging, but infectious diseases are also responsible for more than 40% of deaths.

Locals therefore had to find a biological and cultural strategy to adapt, which means that the population of Papua New Guinea is a "fantastic cocktail" to study genetic adaptation, Ricaut said.

Related: Modern Japanese people arose from 3 ancestral groups, 1 of them unknown, DNA study suggests

Modern humans first arrived in Papua New Guinea from Africa around 50,000 years ago. There, they interbred with Denisovans who'd been living in Asia for tens of thousands of years. As a result of this ancient interbreeding, Papua New Guineans carry up to 5% Denisovan DNA in their genomes.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

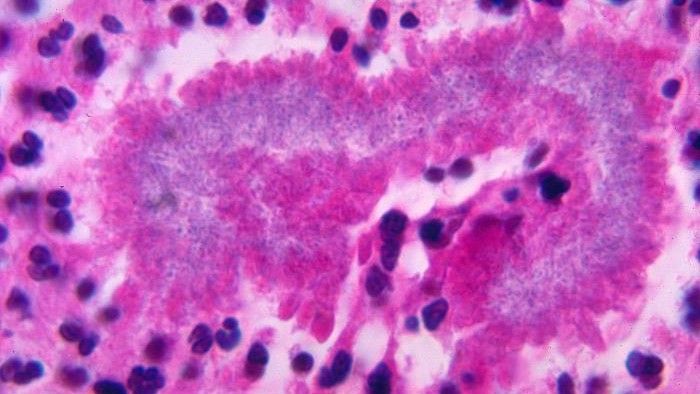

In the new study, published April 30 in the journal Nature Communications, scientists analyzed the genomes of 54 highlanders from Mount Wilhelm who lived between 7,500 and 8,900 feet (2,300 and 2,700 meters) above sea level, and 74 lowlanders from Daru Island, who lived less than 330 feet (100 m) above sea level.

They found that mutations lowlanders probably inherited from Denisovans boosted the number of immune cells in their blood. The highlanders, meanwhile, evolved mutations that raised their red blood cell count, which helps reduce hypoxia at altitude. That's not unusual, as people from several other high-altitude environments have evolved different mutations to combat hypoxia.

The Denisovan gene variants may affect the function of a protein called GBP2 that helps the body fight pathogens that are only found at lower altitudes, such as the parasites that cause malaria. These genes may therefore have been selected during evolution to help people fight off infection at lower altitudes where pathogens are rife, the team said.

Going forward, the team wants to uncover how these mutations bring about changes in the blood of Papua New Guineans, Ricault said. To decipher this, they'll need to investigate how these mutations impact the activity of the genes in which they are found.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30. (emily.cooke@futurenet.com)