People with this rare genetic condition can't repair damage to their DNA

LIG4 syndrome is an exceptionally rare disorder caused by a genetic mutation that prevents the body from repairing damaged DNA.

Disease name: DNA ligase IV (LIG4) syndrome

Affected populations: LIG4 syndrome is an extremely rare inherited condition that was first reported in the U.K. in 1990. Little is known about its exact prevalence worldwide, but as of 2020, approximately 55 cases had been described in the medical literature.

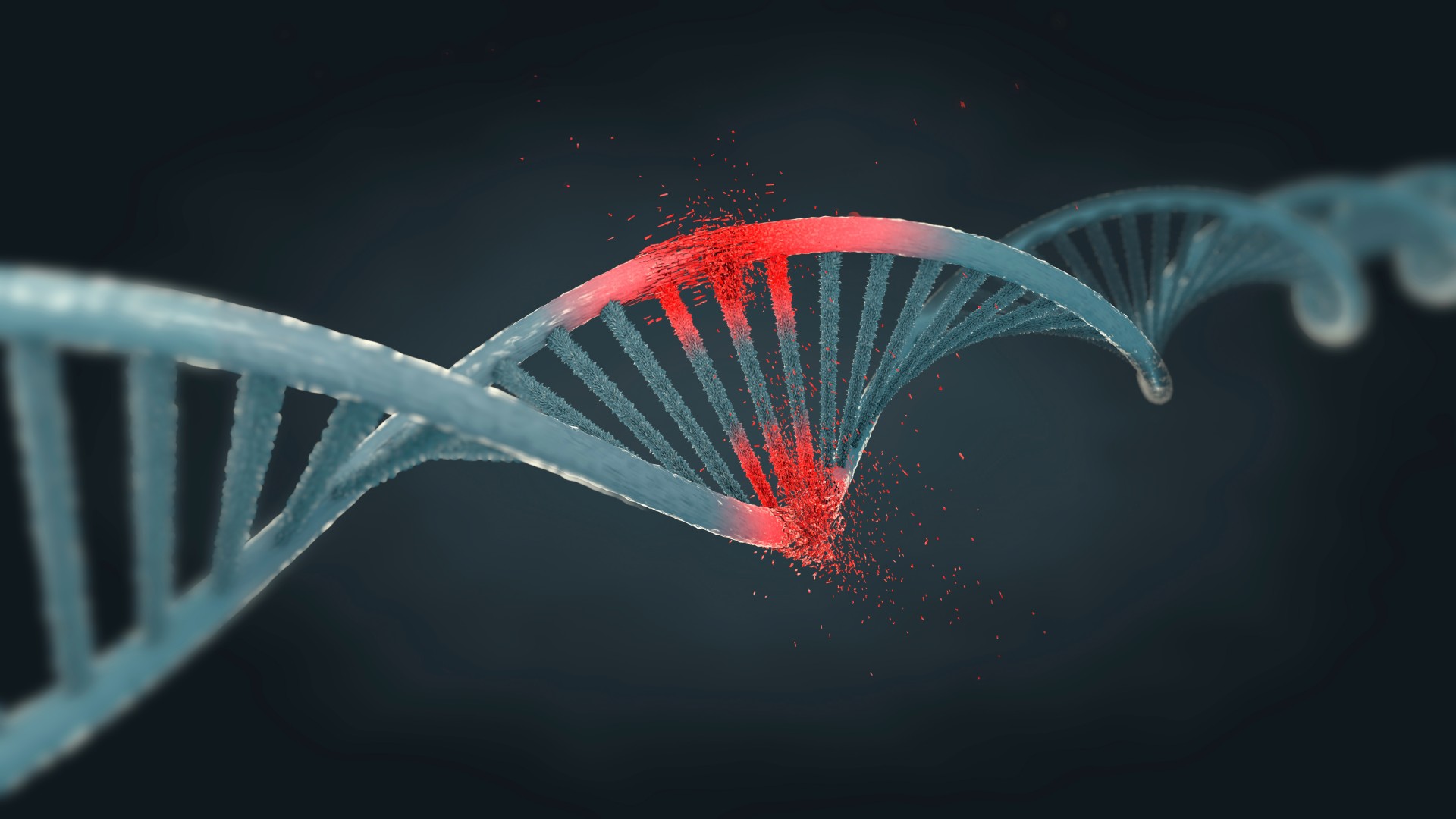

Causes: LIG4 syndrome is caused by a mutation in the LIG4 gene, which carries the instructions needed to make a protein known as DNA ligase 4. This protein is an enzyme that helps repair a specific type of DNA damage —- namely, breaks in both sides of the DNA double helix structure.

These kinds of breaks are commonplace, occurring between 10 and 50 times a day in the average cell in the human body. The breaks are caused by a variety of things, including normal cellular processes like DNA replication, which is needed for cells to multiply, as well as external factors, like exposure to certain chemicals or radiation.

Related: New study provides first evidence of non-random mutations in DNA

If these DNA breaks aren't repaired, they can prompt cells to self-destruct, or failing that, become cancerous. As LIG4 syndrome impairs this response, people with the condition are particularly susceptible to the knock-on effects of radiation.

The enzyme DNA ligase 4 is also needed to make vital proteins on the surface of immune cells called T cells and B cells that help them to work properly and produce antibodies that fight off infections. Hence, people with LIG4 may also develop an immunodeficiency disorder, such as severe combined immunodeficiency, as a result of their condition.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

LIG4 syndrome is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner, meaning that a child needs to inherit two copies of the faulty LIG4 gene — one from each parent — in order to develop the condition.

Symptoms: People with LIG4 syndrome typically experience an array of symptoms, which may either develop soon after birth or later in life. These symptoms include microcephaly, when a baby's brain is much smaller than expected; delays in growth and development; and a reduction in the amount of cells in the blood, including immune cells that help the body to fight infections.

Other characteristic symptoms of LIG4 syndrome are a "bird-like" appearance of the face, as well as skin lesions. People may also have an abnormally-shaped skeleton and develop progressive failure of the bone marrow; bone marrow is a key site of antibody and blood-cell production, so this can cause widespread problems.

Treatments: There is currently no cure for LIG4 syndrome.

However, patients may be offered treatments to help lower their risk of developing severe infections as a result of their immunodeficiency. For example, they may be prescribed antiviral and antifungal drugs or antibiotics.

People with LIG4 syndrome may also receive injections of antibodies to replace defunct ones and they are often advised to avoid any unnecessary exposure to radiation, such as X-rays produced by medical equipment, to minimize potential DNA damage.

According to medical case reports, 10 people with LIG4 syndrome have also reportedly been given a bone marrow transplant in a bid to treat their condition by replenishing their stocks of immune cells. This procedure was successful for six of the 10 individuals. However, the remaining four still died despite treatment — mainly because of infections.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.