Restless legs syndrome tied to 140 'hotspots' in the genome

A new study has identified more than 140 novel genetic risk factors associated with the development of restless legs syndrome.

Researchers have uncovered more than 140 sections of the human genome tied to restless legs syndrome (RLS), a neurological condition that affects up to 10% of the U.S. population.

These stretches of DNA in the genome are known as genetic risk loci, and prior to the new study, only 22 were known to be tied to RLS. The new research, published Wednesday (June 5) in the journal Nature Genetics, increases that number to 164.

Three of the newfound risk loci are located on the X chromosome, which females typically carry two of in each cell while males carry only one. RLS is more common among women than men, but based on their new results, the researchers don't think this difference is explained by the trio of risk loci on the X chromosome.

"This study is the largest of its kind into this common — but poorly understood — condition," Steven Bell, co-senior study author and an epidemiologist at the University of Cambridge, said in a statement. "By understanding the genetic basis of restless legs syndrome, we hope to find better ways to manage and treat it, potentially improving the lives of many millions of people affected worldwide."

Related: 10 unexpected ways Neanderthal DNA affects our health

This discovery could also be used to help predict a person's risk of developing RLS, the study authors wrote in their paper.

RLS, also called Willis-Ekbom disease, causes people to experience an unpleasant crawling or creeping sensation in their legs, as well as the irresistible urge to move them. These sensations are often more intense in the evening or at night, while people are resting. The condition is thought to be underdiagnosed, and when it is diagnosed, its exact cause is often unknown. RLS can arise due to another condition, such as iron deficiency, kidney disease or Parkinson's, and it's likely tied to dysfunction in part of the brain that uses dopamine to control movement.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

There is currently no cure for RLS, but certain treatments, such as anti-seizure drugs, can help ease a person's symptoms.

In the new study, the researchers pooled the data from several, enormous genome-wide association studies, which compare the DNA of people with a given disease to that of people without it. In all, the new research included data from more than 116,000 people who had RSL with more than 1.5 million people without the condition.

Notably, all those included were of European ancestry, which may limit the relevance of the findings in other demographics.

The researchers found no strong differences in genetic risk factors between the sexes, even though RLS is more common in women. They think this suggests that RLS is governed by a combination of genetic, environmental and hormonal factors, so the genetic risk loci don't dictate a person's risk in isolation.

Among the newfound risk loci, the team hunted for genes that might already be targeted by existing approved drugs — the goal was to find treatments that potentially be given to patients in the near future.

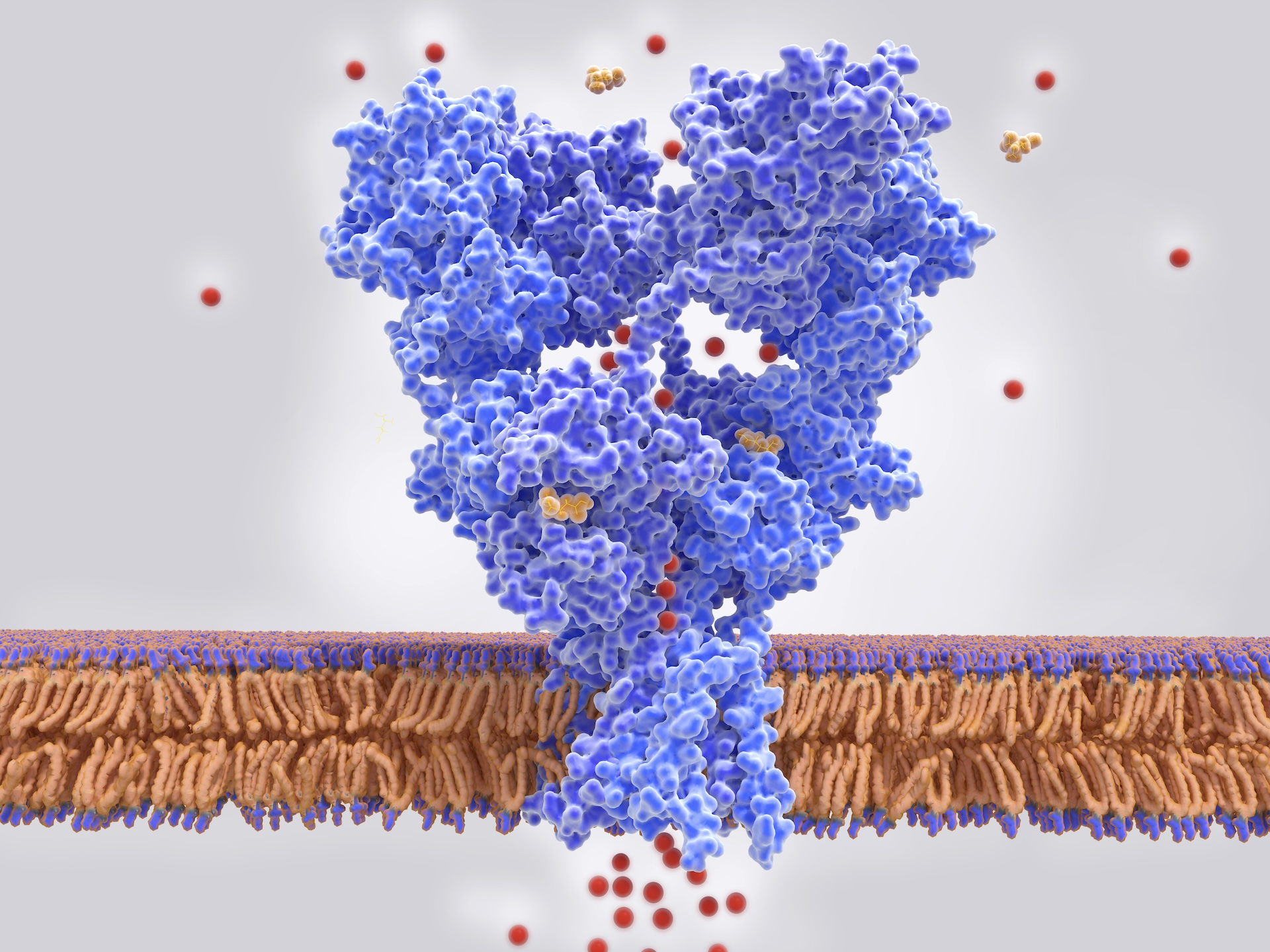

They found 13 risk loci targeted by existing drugs, including two genes that code for so-called glutamate receptors. These receptors are proteins found on nerve cells that play a vital role in the transmission of signals throughout the nervous system. Preliminary clinical trials suggest that targeting these two receptor genes with anti-epileptic drugs — namely, perampanel and lamotrigine — can benefit some patients with RLS.

In addition to identifying potential drugs, the team ran a statistical analysis to see if RLS raises the risk of any other conditions. This suggested that RLS may be a risk factor for developing type 2 diabetes, although past studies on the potential link have found mixed results. As such, "these results should not be overinterpreted," the researchers cautioned — they need to be confirmed in future research.

Despite their limitations, the findings may bring doctors one step closer to being able to predict someone's risk of developing RLS and understanding the wider impacts the condition has on people's health, the team said.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30. (emily.cooke@futurenet.com)

- Nicoletta LaneseChannel Editor, Health