The mystery of the disappearing Neanderthal Y chromosome

Non-Africans carry around 2% Neanderthal DNA in their genomes — yet there's one chromosome where DNA from our ancient cousins is nowhere to be found.

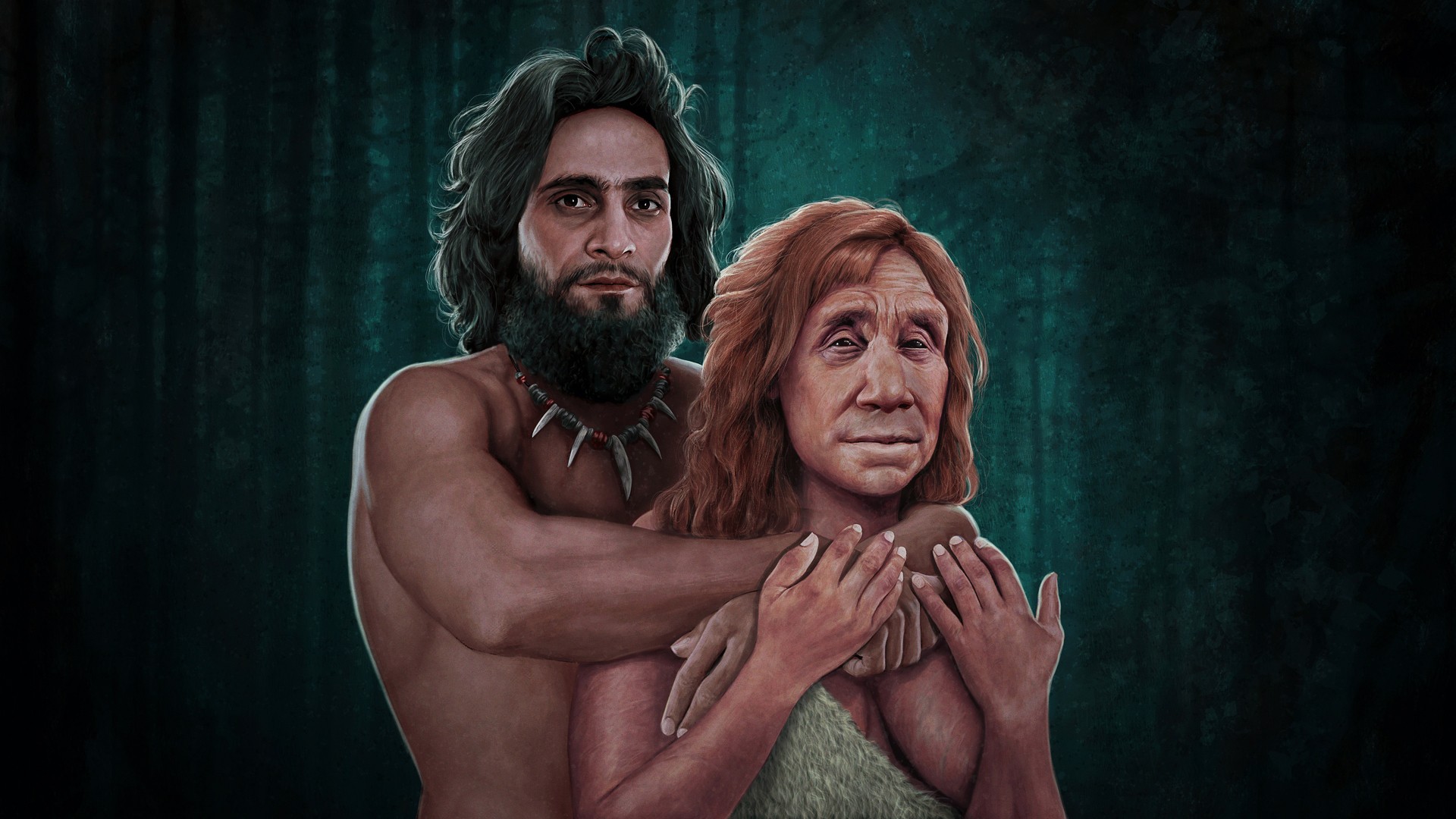

At several points in our tangled history, modern humans mated with Neanderthals.

This has left a telltale signature in the genomes of modern humans today, and this Neanderthal DNA impacts our health in myriad ways.

However, there's one part of our genome that lacks any Neanderthal DNA: the Y chromosome. But why?

Experts told Live Science that some of that could be chance. But it's also possible that genes from Neanderthal males were incompatible with the female Homo sapiens carrying them. That would mean only female hybrids were able to reproduce.

Related: Neanderthal woman's face brought to life in stunning reconstruction

The vanishing "Y"

The Y chromosome is one of two types of sex chromosomes in humans. Females carry two copies of the X chromosome, while males carry one X and one Y chromosome. The Y chromosome can only be passed from father to son.

At first, scientists had been analyzing DNA taken from the fossilized remains of female Neanderthals. However, in 2016, a study published in the American Journal of Genetics examined a Neanderthal Y chromosome from a 49,000-year-old male from Spain.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We've never observed the Neanderthal Y chromosome DNA in any human sample ever tested," Carlos Bustamante, co-senior study author and a population geneticist at Stanford University, said in a statement at the time.

So why might this Neanderthal DNA have seemingly vanished without a trace?

The simplest answer may be that it was randomly lost from the human gene pool over thousands of years.

"The amount of Neanderthal DNA in modern humans nowadays is relatively low so it could have been lost by drift," Fernando Mendez, lead study author, who at the time was a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford, told ABC News. In other words, it's not that Neanderthal DNA was less "fit" than modern human DNA from an evolutionary perspective but rather that it was just lost over time.

Another possibility is that the Neanderthal Y chromosome was incompatible with our own DNA. For instance, the team discovered that three of the Neanderthal genes on the Y chromosome that differ from those found in humans function as part of the immune system. These genes allow the immune system to differentiate friend — aka the body's own cells — from foe. Failure to properly distinguish "self" from "invader" is why tissue transplants from men to women can be rejected or why a mother's immune system may attack a male fetus during pregnancy, causing miscarriage.

It's therefore conceivable that the immune systems of modern women consistently attacked male babies who carried Neanderthal DNA on their Y chromosome, leading to recurrent miscarriages and eventually the loss of Neanderthal Y genes.

If modern women who interbred with Neanderthals had fewer boys than other couples, then systematically the boys that live are likely to have fewer boys, Mendez told ABC News. This hypothesis aligns with an old theory called "Haldane's rule," which suggests that if breeding between genetically-different populations leads to infertility, it is likely to be in the sex — in this case male—that carries two different sex chromosomes.

Far-reaching loss

This isn't the first time in our evolutionary history that the Neanderthal Y chromosome failed to compete with its modern human counterpart.

Between 550,000 and 765,000 years ago, the population that would give rise to Homo sapiens diverged from Neanderthals and another group of now extinct human relatives called Denisovans.

However, a study published in the journal Science in 2020 revealed that sometime between 370,000 and 100,000 years ago, Neanderthals and early modern humans interbred. By 100,000 years ago, the Neanderthal Y was completely replaced by the one from Homo sapiens.

Scientists don't know why this happened, Martin Petr, a co-senior study author and researcher and programmer at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark, told Live Science.

But a likely explanation, Petr hypothesized, is that for hundreds of thousands of years, Neanderthals had a very low population size compared with early modern humans. Low population sizes allow harmful mutations to accumulate within the gene pool at a higher rate than within a larger population, he said.

If you then introduce "healthier" early modern human DNA into the mix, natural selection would favor this modern human DNA, which would have then swept through the Neanderthal population.

However, without a lot more genomic data from Neanderthals that would allow scientists to study the functional impact of inheriting this early modern human DNA, this is only a hypothesis, Petr said.

Related: Scientists finally solve mystery of why Europeans have less Neanderthal DNA than East Asians

Many unknowns

Unfortunately, it's still too early to definitively say why Neanderthal Y DNA was lost in both these instances, Adam Siepel, a computational biologist at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York, told Live Science in an email.

It's still possible the replacement occurred due to random genetic drift, he added.

'More Neanderthal than human': How your health may depend on DNA from our long-lost ancestors

Read more:

—10 unexpected ways Neanderthal DNA affects our health

—What's the difference between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens?

Generally-speaking, the loss of a Y chromosome lineage due to interbreeding is not a rare phenomenon, Carles Lalueza-Fox, co-author of the 2020 Science study and a paleogenomics researcher at the Institut de Biologia Evolutiva in Spain, told Live Science in an email.

This is because the Y chromosome is only inherited paternally, he said. This is opposed to other chromosomes in the body that are passed on to the next generation by both parents. This means that the Y chromosome is more prone to being "lost" over time, he said.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30.