The world's 1st CRISPR therapy has been approved. Here's everything you need to know

Drug regulators have approved a CRISPR therapy called Casgevy to treat inherited blood disorders. But what is it and how does it work?

The world's first treatment that uses CRISPR gene-editing technology has been approved.

Exa-cel, also known by its brand name Casgevy, received its first regulatory approval on Nov. 16, 2023 from the U.K. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) to treat two debilitating blood disorders: sickle-cell disease and transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) later approved the therapy as a treatment for both disorders.

The regulators' historic decision to approve Casgevy may signal the start of a new era of gene therapy. However, questions remain surrounding the treatment's affordability and its long-term safety.

Here's what we know so far about Casgevy.

Related: A teen's cancer is in remission after she received new cells edited with CRISPR

What does the first approved CRISPR therapy treat?

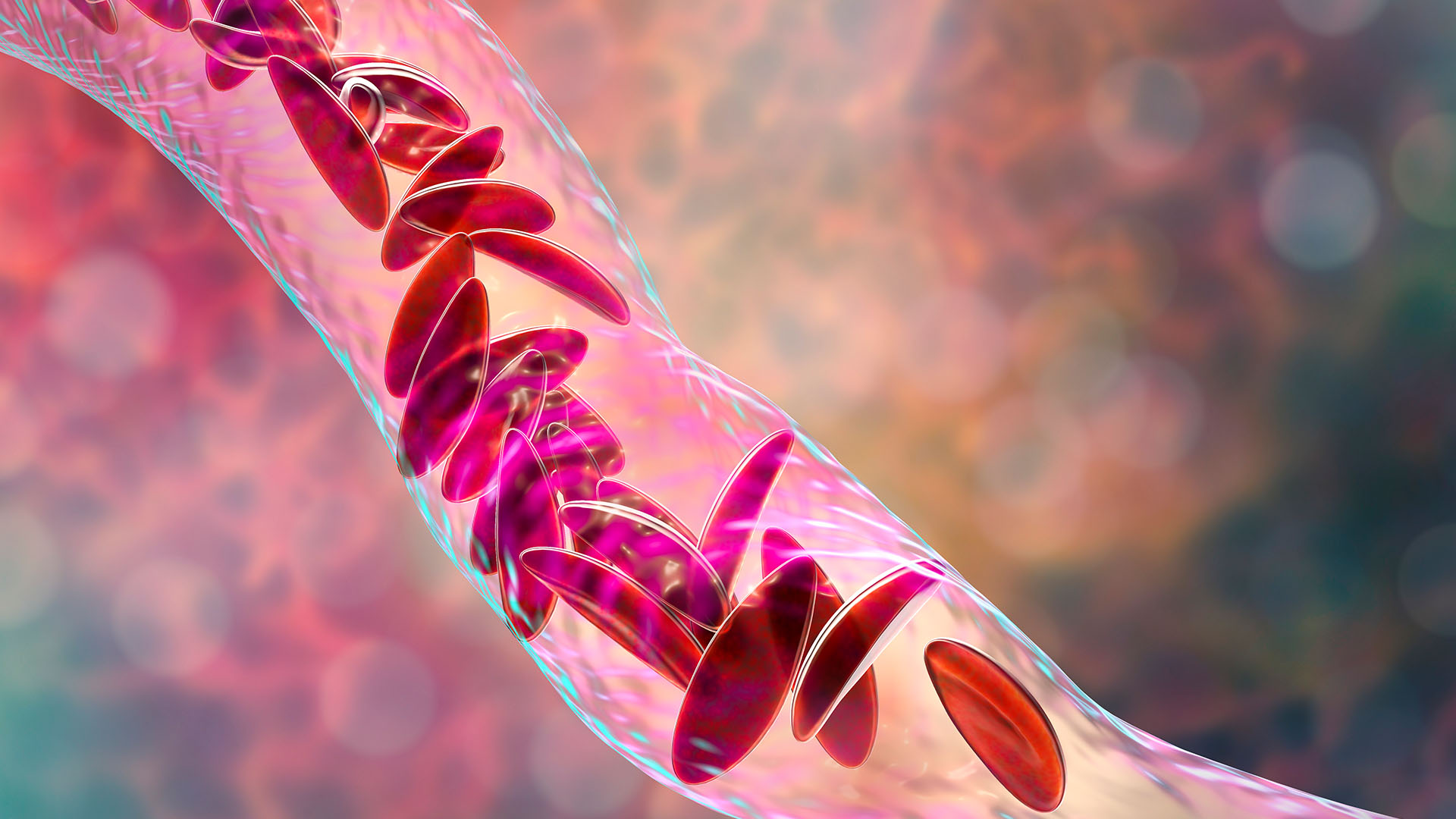

The MHRA approved Casgevy to treat sickle-cell disease (SCD) and transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia. These are lifelong, genetic disorders caused by mutations in the genes that code for hemoglobin, a protein that red blood cells need to transport oxygen around the body.

More than 100,000 people in the U.S. are estimated to have SCD, but the rates are higher for some populations than others. For instance, 1 in every 365 Black babies is born with SCD. The disease changes the shape of a person's red blood cells so that they become C-shape, rather than round. The sickle-like cells die quickly and also stick to each other, blocking blood vessels. As a result, patients develop anemia and often experience bouts of severe pain called pain crises.

Beta-thalassemia affects around 1 in 100,000 people worldwide, and it disproportionately affects those of Mediterranean, Asian, African and Middle Eastern descent. Patients with beta-thalassemia don't produce enough hemoglobin, which can lead to severe anemia, whereas sickle-cell anemia stems from a lack of healthy red blood cells. "Transfusion-dependent" means that the disease is so severe that patients must have regular red blood cell transfusions throughout their lives.

How does Casgevy work?

Casgevy is based on a revolutionary gene-editing technique called CRISPR which was first developed in 2012 .

The CRISPR system cuts genes out of DNA using an enzyme called Cas9. These "molecular scissors" are guided to target DNA by a molecule of RNA. The technology was adapted from a natural defense mechanism that bacteria and other simple organisms called archaea use against viruses.

Casgevy targets a gene called BCL11A. The gene codes for a protein that would normally regulate the switch from the fetal version of hemoglobin to the adult version shortly after birth. However, in patients with SCD and beta-thalassemia, the adult hemoglobin is defective.

The goal of Casgevy is to disable BCL11A and thus allow the body to keep making fetal hemoglobin, since the adult version doesn't work. To do this, blood-making stem cells are taken from a patient's bone marrow and the BCL11A gene is edited using Casgevy in the lab. The newly-modified cells with functioning hemoglobin are then infused back into the patient's body. Before the infusion, the patient must take a chemotherapy drug called busulfan to eliminate the unedited cells still in their bone marrow, STAT News reported.

This process of adjusting to the new, edited cells is lengthy. "Patients may need to spend at least a month in a hospital facility while the treated cells take up residence in the bone marrow and start to make red blood cells with the stable form of hemoglobin," the MHRA said in a statement.

In two late-stage clinical trials, Casgevy restored hemoglobin production in most patients with SCD and beta-thalassemia and alleviated their symptoms. Twenty-eight out of 29 patients with SCD didn't experience any severe pain crises for at least a year after being treated with Casgevy. Similarly, 39 out of 42 patients with beta-thalassemia didn't need red blood cell transfusions during the same post-treatment period. The remaining three patients were more than 70% less likely to need a transfusion.

Is Casgevy safe?

No serious safety concerns were flagged in either of the two late-stage clinical trials of Casgevy, although some transient side effects, such as fever and fatigue were reported. Both of these trials are ongoing and Casgevy's long-term safety continues to be monitored by regulatory bodies, such as the MHRA and the FDA, and by the therapy's manufacturers, Vertex Pharmaceuticals and CRISPR Therapeutics.

However, there are still some concerns about the safety of CRISPR-based therapies, in general. Namely, there's concerns about "off-target" effects, which occur when Cas9 acts on other parts of the genome that weren't intended to be changed and cause unwanted side effects.

"It is well known that CRISPR can result in spurious genetic modifications with unknown consequences to the treated cells," David Rueda, chair of Molecular and Cellular Biophysics at Imperial College London, told the U.K. Science Media Centre. "It would be essential to see the whole-genome sequencing data for these cells before coming to a conclusion," he said. This would involve surveying all the DNA in Casgevy-edited cells to see if there are any off-target effects.

Related: 2 women earn Chemistry Nobel Prize for gene-editing tool CRISPR

Where has Casgevy been approved?

In November 2023, the U.K. approved Casgevy for people over the age of 12 with either sickle-cell disease or transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia. In December, the FDA approved the treatment for people ages 12 and older with sickle-cell disease and in January 2024, the agency approved Casgevy for people with transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia belonging to the same age category.

According to Vertex, the treatment is currently being reviewed by the European Union's European Medicines Agency and the Saudi Food and Drug Authority, so additional countries may soon approve Casgevy.

When will Casgevy be available to patients?

It's unclear when Casgevy will become available, but its reach will largely depend on its cost. Gene therapies can cost millions of dollars and it looks like Casgevy will be no exception. This could make it inaccessible for many people who need it.

"The challenge is that these therapies will be very expensive so a way of making these more accessible globally is key," Kay Davies, a professor of anatomy at the University of Oxford, told the U.K. Science Media Centre.

Vertex has yet to set a price for Casgevy in the U.K., a spokesperson from the company told Nature, but is "working with the health authorities to secure reimbursement and access for eligible patients as quickly as possible."

What other CRISPR therapies are in development?

Intellia Therapeutics is developing CRISPR therapies to treat inherited diseases from inside the body, STAT News reported.

In addition, a tweaked version of CRISPR called "base editing" that can target the individual building blocks of DNA is being tested as a way to treat disease. For example, Verve Therapeutics is testing such an experimental treatment for heart disease. Another promising new type of therapy, called "prime editing," involves CRISPR but also "incorporates additional enzymes and genetic instructions to insert, delete or rewrite short segments of DNA," STAT News reported.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Editor's note: This story was last updated on Jan. 18, 2024 to reflect the FDA's approval of Casgevy for beta-thalassemia. The article was first published on Nov. 22, 2023 and previously updated on Dec. 8 2023.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30. (emily.cooke@futurenet.com)