This rare disease causes people to move uncontrollably and unintentionally self-harm

Lesch-Nyhan syndrome is an extremely rare disease that affects patients' behavior and cognitive skills.

Disease name: Lesch-Nyhan syndrome

Affected populations: Lesch-Nyhan syndrome is an incredibly rare genetic disorder that causes metabolic changes and mainly affects males. Approximately 1 in 380,000 babies born in the United States are estimated to have the condition.

Causes: Lesch-Nyhan syndrome is caused by mutations in a gene called HPRT1. This gene carries instructions for an enzyme that cells use to recycle important chemical compounds called purines; these are found, for instance, in DNA and in molecules that interact with enzymes. Purines are also present in many foods, such as offal (organ meats), poultry and legumes.

In patients with Lesch-Nyhan syndrome, the HPRT1 enzyme doesn't work properly due to mutations in its associated gene. Therefore, cells cannot recycle purines as they normally would, and a waste product called uric acid consequently builds up in people's blood.

Related: New mRNA therapy shows promise in treating 'ultrarare' inherited disease

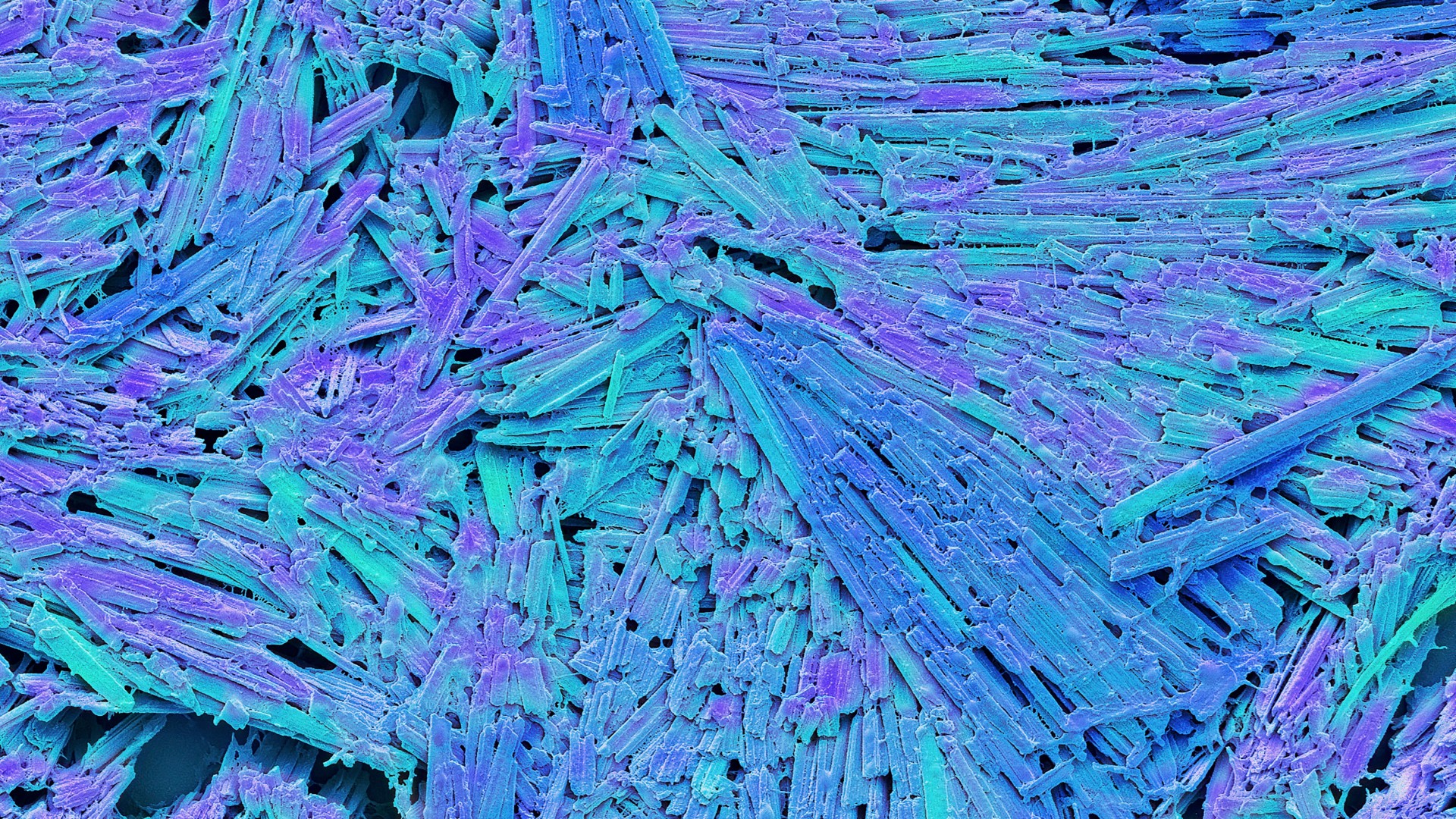

This excess uric acid also clumps into small stones or crystals in different regions of the body, including in the joints and kidneys.

For unknown reasons, patients with Lesch-Nyhan syndrome also have lower levels of the chemical messenger dopamine in their brains, compared with people without the condition. Dopamine plays a key role in controlling movement and processing emotions, among other abilities.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The HPRT1 gene is found on the X chromosome, one of the two sex chromosomes in humans; females typically have two X chromosomes (XX), while males usually have an X and a Y chromosome (XY).

Because females have two X chromosomes, if the HPRT1 gene on one of those chromosomes is mutated, the non-mutated version on their other chromosome can effectively compensate for it. However, because males have only one X chromosome, if they have a mutant HPRT1 gene, they will develop Lesch-Nyhan syndrome. That is why the condition almost exclusively affects males.

Although the syndrome tends to run in families, it can sometimes occur in individuals with no family history of the condition, due to random mutations that emerge in HPRT1 during pregnancy.

So far, more than 600 mutant versions of the HPRT1 gene have been found to be associated with Lesch-Nyhan syndrome.

Symptoms: The main symptoms of Lesch-Nyhan syndrome are associated with inflammatory arthritis — a group of conditions driven by the immune system that cause joint pain, swelling and tenderness. Specifically, people with the syndrome often have gout.

People may also experience kidney and bladder stones and cognitive disability. They may have involuntary muscle movements and engage in self-injurious behaviors, such as lip and finger biting and head banging. These uncontrollable behaviors may be driven by the loss of, or damage to, dopamine neurons in the brain.

Often, patients need help walking and sitting and many require a wheelchair.

Symptoms of Lesch-Nyhan syndrome typically emerge before a child reaches their first birthday.

The main causes of death in patients with Lesch-Nyhan syndrome are a bacterial infection of the lungs called aspiration pneumonia and kidney failure. The aspiration pneumonia often happens because patients develop severe swallowing issues.

Treatments: There is no cure for Lesch-Nyhan syndrome, but with effective clinical care, patients can live until around age 40.

Treatments that can help manage patients' symptoms include muscle relaxants to control involuntary movements, as well as physical restraints or teeth extraction to stop them from injuring themselves.

Disclaimer

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30. (emily.cooke@futurenet.com)

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.