Anxiety and depression raise the risk of dangerous blood clots, study finds

Recent research has drawn a link between anxiety, depression and an increased risk of deep vein thrombosis.

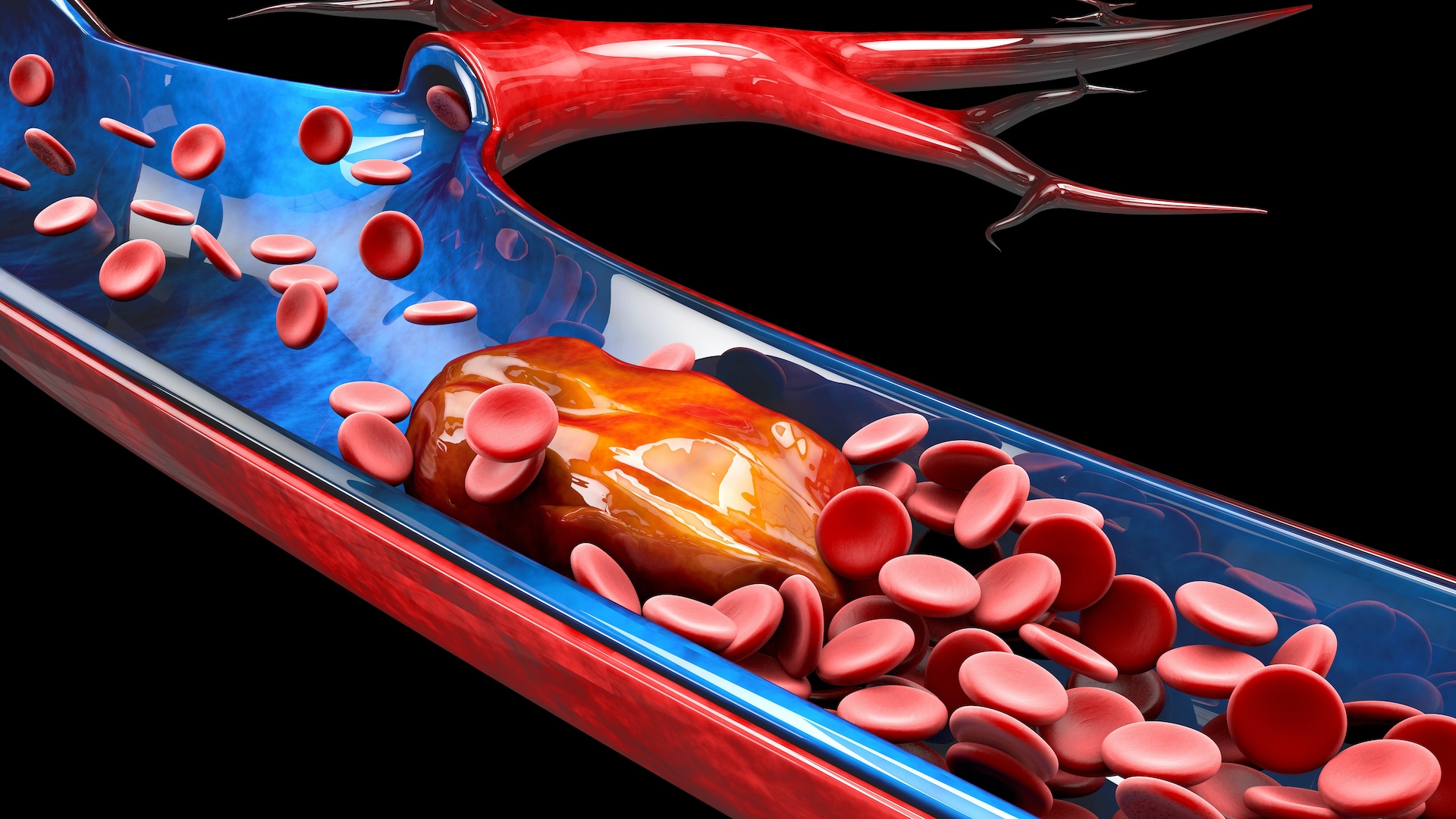

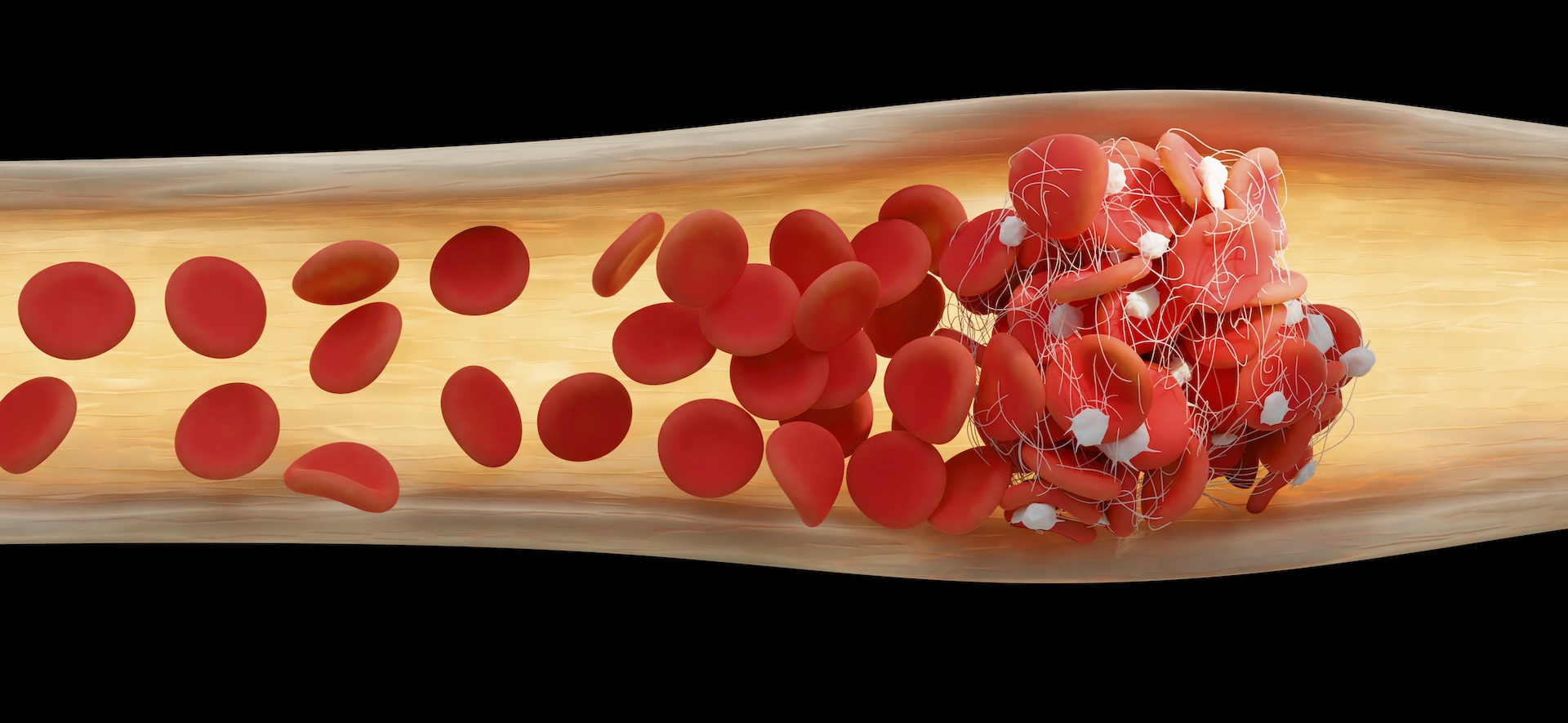

Having anxiety or depression may increase the risk of potentially life-threatening blood clots, known as deep vein thrombosis (DVT).

With DVT, a blood clot forms in a deep vein, usually in the legs. DVT can cause damage by limiting blood flow to the site of the clot and increasing pressure in veins. A larger danger arises if some or all of that clot breaks loose and then travels to the lungs, where it can block blood flow, causing shortness of breath, chest pain and even death.

Within the last decade, scientists have uncovered links between people's mental health and their risk of these blood clots. However, conflicting study results and complicating factors — such as some study subjects' medication use and histories of high blood pressure — have made it difficult to determine exactly how the two are connected.

Now, a study published July 4 in the American Journal of Hematology has examined not only how much anxiety or depression can raise a person's risk of DVT but also why.

Related: Rare clotting effect of early COVID shots finally explained

"My research comes from my patients," Dr. Rachel Rosovsky, lead study author and director of thrombosis research in the Division of Hematology at Massachusetts General Hospital, told Live Science. "When I realized the association between long-term anxiety and depression and blood clots, I started to think about whether those conditions could affect a patient's risk of developing a clot."

To investigate the link, the researchers looked retrospectively at data from almost 119,000 people. The data included measurements of stress-related brain activity obtained using positron emission tomography (PET). PET scans reveal the activity levels and energy use of different parts of the brain.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers compared the activity of the amygdala — a brain region that processes and responds to potential threats — to that of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, which helps regulate the amygdala and thus control emotional responses. In that way, the researchers got a snapshot of stress-related neural activity, or SNA.

The data also included measures of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, a marker of inflammation, and heart rate variability, a measure of adaptability. The higher your heart rate variability, the better your body can cope with stressful situations.

Of the overall group, about 106,450 had a diagnosis of anxiety, while 108,790 had depression; there's overlap in these groups as many participants had both conditions.

Over an average follow-up time of 3.6 years, about 1,780 study participants experienced DVT. Those with a history of anxiety or depression were 53% and 48% more likely to experience DVT, respectively, compared with those with no history of either condition. Similar trends were seen among people with both conditions.

Related: 6 distinct forms of depression identified by AI in brain study

Furthermore, of 1,520 people who got PET scans, those with anxiety or depression showed higher SNA than those without either condition. People with higher-than-normal levels of this activity were 30% more likely to experience DVT than those with normal levels.

"We first showed that anxiety and depression were significantly associated with increased SNA," Rosovsky said. Then, the team found that SNA was associated with increased leukopoietic activity, meaning the creation of white blood cells — a driver of inflammation.

This had previously been shown to "promote clotting through many different mechanisms," she said. And now, the team has connected the dots from anxiety and depression to SNA and on to DVT risk.

Three potential mechanisms connect anxiety and depression to DVT: higher SNA, higher inflammation and reduced heart rate variability. It appears that the more stress a person experiences, the higher their risk of DVT, the researchers concluded.

This "intriguing study" sheds light on how SNA influences the production of blood in the body, said Kamran Mirza, a professor of hematopathology at the University of Michigan who was not involved in the study. It reveals a "potential connection between mental health and increased clotting risk that warrants further investigation," Mirza told Live Science.

Notably, the researchers were limited to data that had already been collected. Prospective studies that follow people over time would enable scientists to track changes in stress and inflammation and see how they relate to DVT. The team plans to examine how treating anxiety or depression might affect DVT rates, and they also want to see if somehow reducing SNA could reduce risk.

"If you have depression or anxiety, be aware that those are potential risk factors for blood clots," Rosovsky said. "But also think about whether you have other risk factors and what you can do about those to reduce your risk."

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Michael Schubert is a veteran science and medicine communicator. He writes across all areas of the life sciences and medicine but specializes in the study of the very small — from the genes that make our bodies work to the chemicals that could support life on other planets. Mick holds graduate degrees in medical biochemistry and molecular biology. When he's not writing or editing, he is co-director of the Digital Communications Fellowship in Pathology; a professor of professional practice in academic writing at ThinkSpace Education; an inclusion and accessibility consultant; and (most importantly) dog-walker and ball-thrower extraordinaire.