What happens during a heart attack?

A heart attack, or myocardial infarction, happens when oxygen-rich blood does not reach a part of the heart muscle.

A heart attack, or myocardial infarction (MI), is when blood flow to part of the heart muscle (myocardium) is blocked and that part of the organ does not get enough blood.

When their blood supply is reduced, muscle cells in the heart get damaged and die. The more time that passes without blood flow, the greater the damage to the heart muscle. MIs are most often caused by blockages in the arteries that supply blood to the heart muscle, according to the American Heart Association (AHA). The buildup of plaque in these arteries is known as coronary artery disease (CAD), the most common type of heart disease in the U.S.

Every year, about 805,000 people in the United States have a heart attack. One in 5 heart attacks are "silent," meaning they go unnoticed due to the lack of overt symptoms, such as chest pain or shortness of breath, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Silent heart attacks tend to affect more men than women, according to Harvard Health.

Approximately 12% of American adults who have a heart attack die within a month of the event, according to a 2019 study published in the journal JAMA Network Open; this death rate is based on data gathered from Medicare beneficiaries in 2014.

Related: Do other animals get heart attacks?

Heart attack is not the same as cardiac arrest. The former is caused by impaired blood circulation, whereas cardiac arrest happens when the heart suddenly stops beating due to an electrical malfunction in the organ, the AHA said.

What happens during a heart attack?

A heart attack is a medical emergency experienced over minutes or hours, but the groundwork for that event is set years or decades in advance.

The heart is a muscular organ. The average adult heart beats 100,000 times daily, pushing about 1.5 gallons of oxygenated and nutrient-rich blood through the body each minute. Blood first travels from the heart to the lungs where it is re-oxygenated before it returns to the heart to be pumped out to arteries to supply oxygen and nutrients to the brain, digestive tract and rest of the body's tissues.

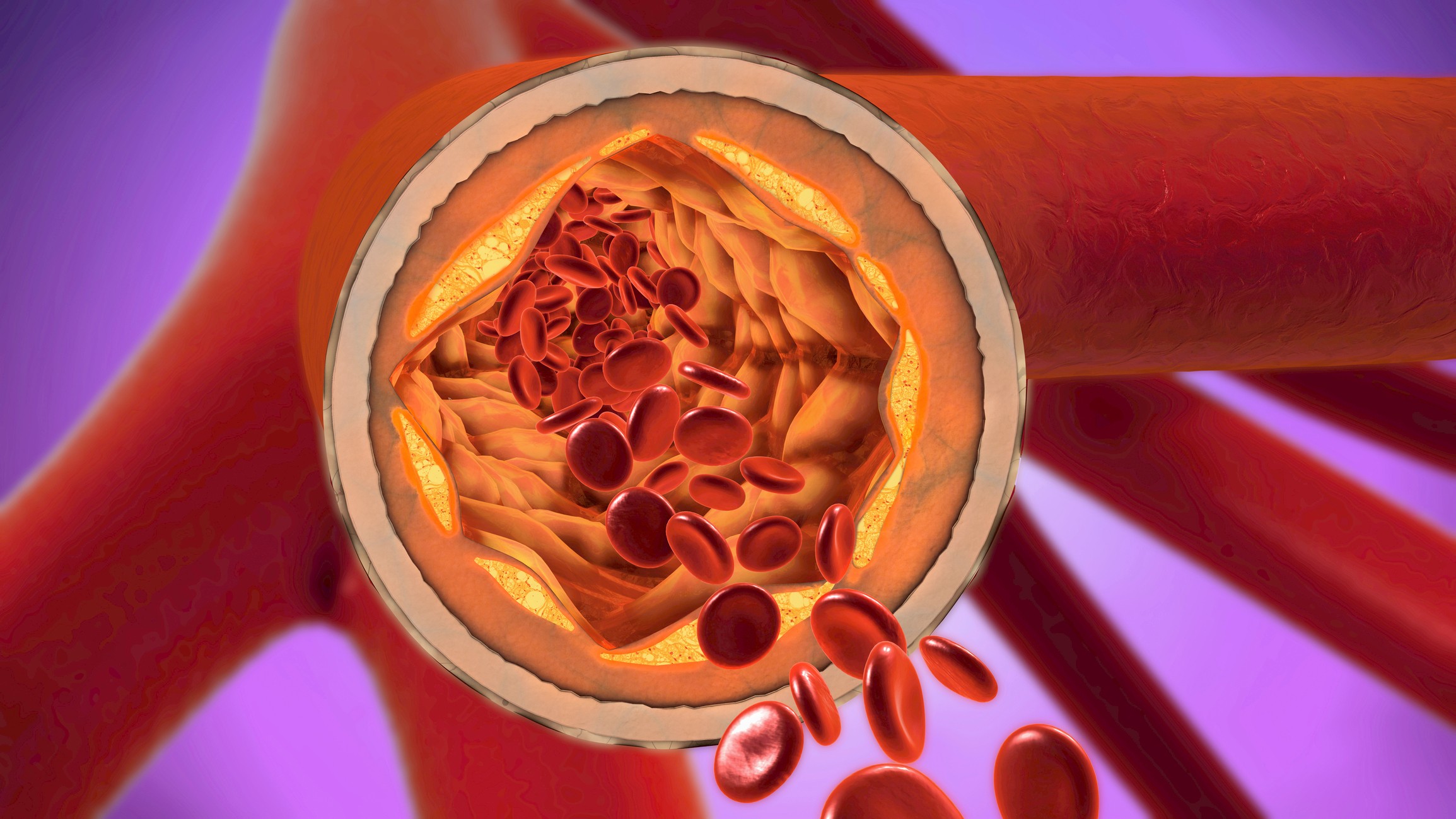

Most often in the leadup to an MI, the two primary coronary arteries that supply oxygen and nutrients to the heart muscle narrow over years to decades, largely due to atherosclerosis, a buildup of fatty plaques in the arterial walls, according to the AHA. Atherosclerotic plaques are hard on the outside and soft on the inside and cause arteries to become rigid, according to the Cleveland Clinic.

Sometimes, the plaques' hard outer surface can crack and blood components called platelets will stick to the cracks, forming blood clots that further narrow the artery.

If the arteries have already been narrowed due to years of atherosclerosis, the clot can completely block the blood supply downstream to the heart. Bits of the plaques can also break off and move through the artery, causing the blockage to rapidly worsen. Such blockages can lead to a heart attack, and within a few minutes, muscle cells in the heart undergo damage and begin to die.

Less commonly, a sudden spasm or contraction of the walls of the coronary arteries can block blood flow to the myocardium and trigger a heart attack, according to Penn Medicine. These spasms occur most often in people who smoke and in people with high cholesterol or high blood pressure, and the spasms can sometimes be driven by alcohol withdrawal or stimulant use, among other triggers.

What are the warning signs of a heart attack?

According to the CDC, the warning signs of a heart attack include:

- Chest pain or discomfort. Most heart attacks involve a feeling of uncomfortable pressure, squeezing, fullness or pain in the center or left side of the chest. This discomfort typically lasts for more than a few minutes before subsiding, or sometimes, it emerges, goes away and then comes back.

- Pain or discomfort in other areas of the upper body, such as jaw, neck, back, arms or shoulders.

- Shortness of breath.

- Feeling weak, light-headed or faint.

- Unusual or unexplained tiredness.

- Nausea or vomiting.

Heart attack symptoms may vary between men and women, although chest pain or discomfort is the primary symptom for both sexes. However, women are more likely to experience other symptoms that are typically less associated with heart attack, such as unusual or unexplained tiredness and nausea or vomiting, according to the CDC.

MIs are more common in the winter months, compared with other times of the year, and they can be triggered by both physical and emotional stressors, such as vigorous exercise, intense fear or anger, according to a 2009 review published in the journal Cardiology in Review.

Genetic factors, tobacco smoking and sedentary lifestyle can increase the risk of a heart attack, the AHA said. Long-term exposure to air pollution may also increase the risk of MI, according to a 2021 meta-analysis published in the journal Frontiers in Medicine.

What is the first treatment for a heart attack?

The first treatment for a heart attack involves removing the blood clot or plaque that's blocking the artery to limit the damage to the heart muscle, according to the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI).

Time is a critical factor. If a patient gets to a hospital quickly, doctors can restore the heart's blood supply and prevent or limit the damage.

Blood flow can be restored through angioplasty (a non-invasive nonsurgical procedure used to widen narrowed or obstructed arteries), stenting (inserting a small mesh tube that holds open weak or narrow arteries) or coronary artery bypass grafting (an open-heart surgery used to restore blood flow in severe heart attacks). Patients may also be given medications to prevent further blood clotting, such as aspirin, the NHLBI says.

Additional treatments can include nitroglycerin, or nitrates, which improve blood flow in the coronary arteries and ease chest pain, as well as thrombolytic medicines, which help dissolve blood clots, according to NHLBI.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Anna Gora is a health writer at Live Science, having previously worked across Coach, Fit&Well, T3, TechRadar and Tom's Guide. She is a certified personal trainer, nutritionist and health coach with nearly 10 years of professional experience. Anna holds a Bachelor's degree in Nutrition from the Warsaw University of Life Sciences, a Master’s degree in Nutrition, Physical Activity & Public Health from the University of Bristol, as well as various health coaching certificates. She is passionate about empowering people to live a healthy lifestyle and promoting the benefits of a plant-based diet.