How does the brain regulate body weight?

An almond-shaped structure deep in the brain controls people's feelings of hunger and fullness in an attempt to keep them at a constant body weight. In obesity, its signaling can be disrupted.

The diabetes drug Ozempic has dramatically reshaped weight-loss treatment. Combined with dieting and exercise, weekly injections of the drug can help people drop 15% of their weight. However, Ozempic doesn't directly change the body's ability to burn fat. Rather, it works in part by altering the brain's response to food.

So how does the brain regulate body weight?

Each of us has a given weight — known as a set point — that our brain wants to maintain, much in the same way it keeps body temperature within certain limits, Dr. Michael Schwartz, a professor of medicine at the University of Washington, told Live Science. Over the course of human evolution, those that maintained their body fat at a constant level were more likely to survive periods of food scarcity, as well as avoid health problems that come with being overweight, he said.

Set point theory explains why diets so often fail: The brain "wants" to keep people at a higher weight than average, and sends out chemical signals that spur hunger and other cues that make it hard to shed pounds. People who do manage to lose that weight struggle to keep it off over the long term for the same reason.

It's the "single biggest obstacle to long-term weight loss," Schwartz said.

When we eat, the gut secretes hormones and small peptides — tiny fragments of proteins — into the bloodstream, including glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), which Ozempic messes with, and ghrelin, which helps regulate hunger. These chemicals reach the brainstem via the gut-brain axis, a communication highway between the gut and brain.

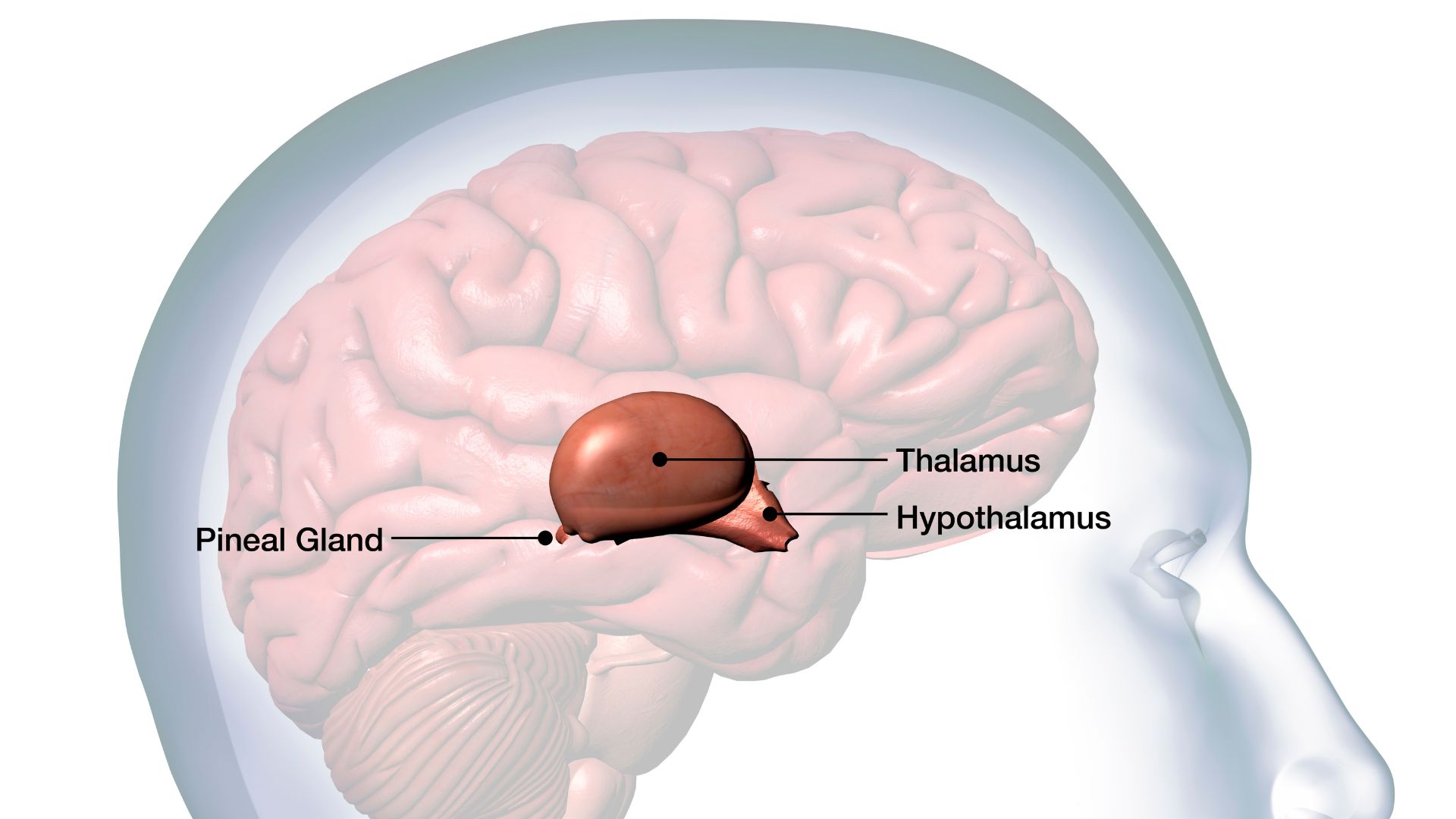

The brainstem then sends signals to the hypothalamus, an almond-shaped structure deep inside the brain, that makes people feel full. The hypothalamus — the brain region that defends the set point — keeps tabs on both how much people are eating and their stored body fat. It detects the hormone leptin, which is released in direct proportion to the percentage of fat tissue.

If leptin levels fall below the range dictated by the set point, the hypothalamus sends out a flurry of signals to the rest of the brain, Schwartz said. The resultant brain changes make people feel hungrier, make food more rewarding and reduce sensitivity to pain — or anything that might distract people from eating.

Neurons within the hypothalamus also switch on motor neurons that plug into the jaw, resulting in chewing movements. This chain of events relies on a simple circuit in the brain, consisting of three types of neurons. If that circuit is activated, an animal will start chewing regardless of whether there is any food around, according to a 2024 study published in the journal Nature. Researchers found this simple brain circuit in mice and they expect something similar is in people.

If the brain is hardwired to maintain a certain body weight, how do people become obese?

There are conflicting hypotheses among obesity researchers, but one theory involves so-called AgRP neurons, a cluster of brain cells in the hypothalamus. These cells play a powerful role in appetite: Inhibiting the neurons in adult mice causes the animals to ignore food, even to the point of starvation, while stimulating them triggers uncontrollable eating.

Under normal conditions, AgRP neurons are kept quiet by hormones and nutrients that signal energy surplus — including leptin, insulin and glucose. Interestingly, even the sight of food is enough to dampen the cells' activity.

Related: Doctors identify never-before-seen genetic mutations that led to 2 children's insatiable hunger

But when mice are fed a high-fat diet, support cells called glia, which surround the AgRP neurons, become activated and increase in number. This response, called gliosis — which is typically seen when neurons are damaged — has also been detected in brain scans of people with obesity.

Some scientists propose that gliosis may prevent AgRP neurons from detecting the body's inhibitory, "keep quiet" signals, Schwartz said. When researchers show obese mice food, their AgRP neurons are 50% to 70% less inhibited than when their lean littermates are presented with food.

And this reduced sensitivity to inhibitory signals could lead to dramatic weight changes. If the hypothalamus detects only half of the body's total leptin levels, it will miscalculate stored fat levels as much lower than its set point, triggering brain signals that increase cravings and promote weight gain, Schwartz explained.

So how does semaglutide, the active ingredient in Ozempic and the related weight-loss drug Wegovy, trick the brain into losing weight?

The drug mimics GLP-1. By binding to GLP-1 receptors in the brainstem, it stimulates the neural circuits that make people feel full. This is thought to counteract the appetite-inducing signal from AgRP neurons, thereby reining in cues from the hypothalamus that would trigger more eating.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Editor's note: This article was updated on Nov. 4, 2024 to include information about the brain circuit in mice. The original article was published on July 27, 2023.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Holly Barker is a freelance science journalist based in the U.K. She holds a PhD in clinical neuroscience from King's College London and a BSc degree in biochemistry from the University of Manchester. She has previously written for Spectrum News, The Scientist and Discover.