Inflammation is a 'mismatch between our evolutionary history and modern environment,' says immunologist Ruslan Medzhitov

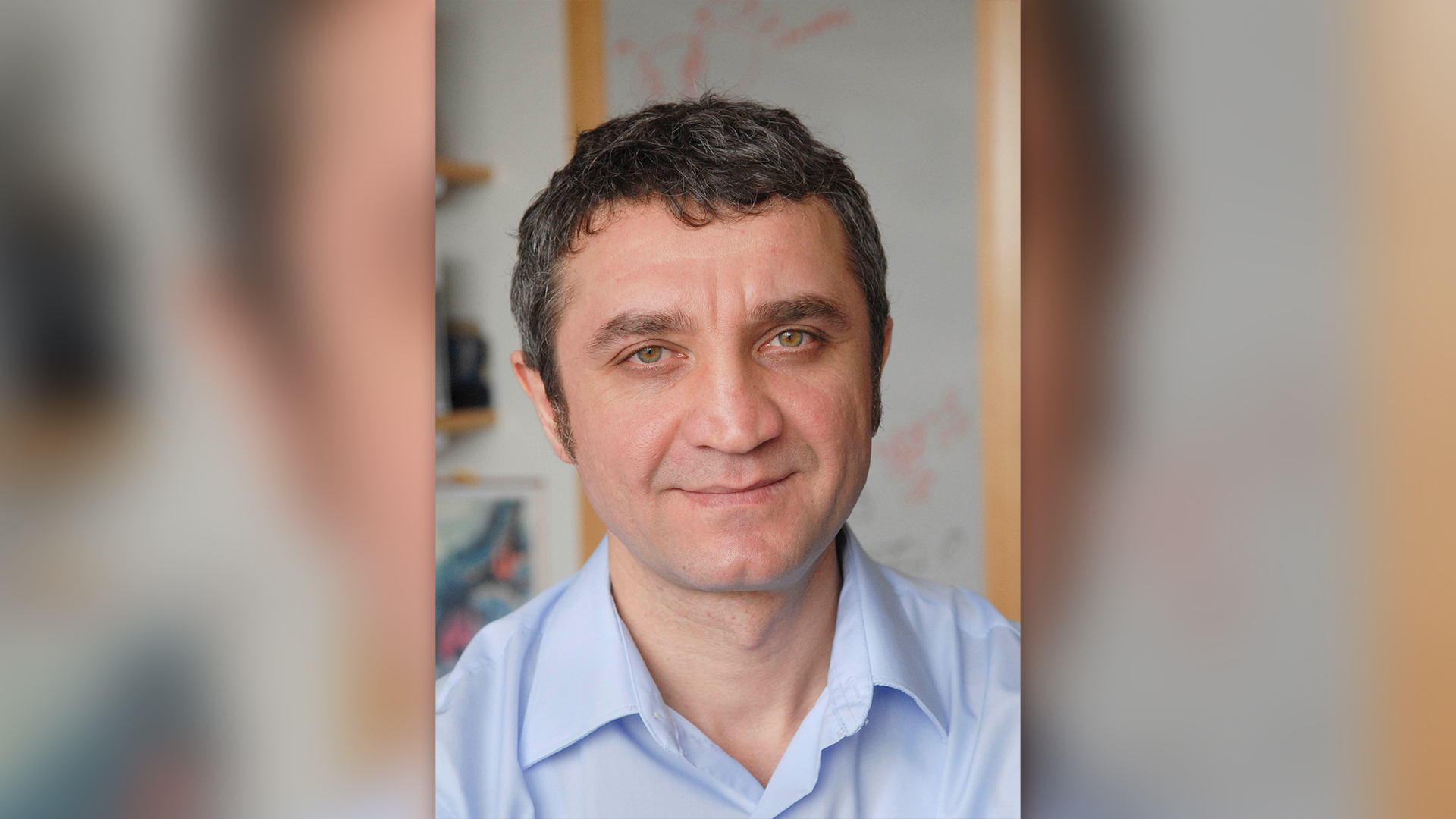

In this interview, immunologist Ruslan Medzhitov explains how fundamental inflammation is, why it often goes wrong, and whether there's anything we can do about chronic inflammation.

"Inflammation is the new evil. Let me explain."

"You might think inflammation isn't really THAT big of a deal…but trust me when I say it is."

Scan social media and you'll easily find content that portrays inflammation as a villain.

In every bookstore you'll find at least one anti-inflammatory diet recipe book, and in your local drug store, an array of products parading their magical anti-inflammatory ingredients.

But inflammation has evolved over millennia to protect us, says Ruslan Medzhitov, a Sterling Professor of Immunobiology at Yale University School of Medicine and Investigator at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute in Maryland who studies inflammation in the context of autoimmune disease and allergies.

So if not all inflammation is bad for us, how do we know the difference between "good" and "bad?"

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Live Science spoke with Medzhitov about how inflammation is the body's response to a system out of equilibrium, how chronic inflammation results from a mismatch between our evolutionary environment and the modern one, and whether there's any evidence for specific "anti-inflammatory" diets.

Emily Cooke: What is inflammation?

Ruslan Medzhitov: Inflammation is an essential part of our defense system. It evolved to protect us from a variety of challenges, including many challenges that come from the outside world, such as infection or injury or toxins. Without inflammation, we would quickly succumb to infections and die and that would be the end of it.

Mostly what we know about inflammation is what happens at the extreme, when there is an infection or injury and then there is swelling and redness and fever and things like that. But inflammation plays an important role in a variety of settings, including when we don't diagnose it clinically as inflammation, including when we may not even feel it, it's asymptomatic.

Under the hood, it plays an important role in coordinating metabolism, different physiological functions and so forth. Those functions of inflammation are much, much less appreciated and much less studied. And just to give one quick example of the reach of inflammation throughout biology is that it controls our metabolism, controls adaptation to the environment in terms of thermogenesis [heat production] and [even controls] aspects of behavior. And that last part is what's particularly interesting, where inflammation can for example, control mood. It can control avoidance behaviors, and anxiety behaviors. And these are all presumably by design, meaning that these are meant to be protective phenomena, they're beneficial in certain settings. When this response becomes dysregulated in some way, it can lead to particular types of pathologies and disorders and so forth that inflammation unfortunately is more famous for.

Related: Brain inflammation may drive mood changes in Alzheimer's

EC: Is there such a thing as "good" and "bad" inflammation?

RM: Yes, and there are two ways to divide between good and bad inflammation.

So, good inflammation operates within the normal range. What is "normal" is decided not by us, by how we feel. It is decided by millions of years of evolution and calibrated by, on average, if you have this type of response, on average you have a better chance for survival. But that was in a very, very different setting. Throughout our evolutionary history, of course, our environment was very different. But the genes that evolved under those conditions, we still have them and they still operate as if nothing [has changed], because dramatic change in the environment happened only very recently.

Good inflammation will be the one that operates with the right magnitude, that provides maximum benefit and lowest possible cost.

But that line is very fuzzy and one can shift into what would be now called "bad" inflammation, which is a protective response but in overdrive.

Phenomena like cytokine storms [when chemical signals associated with inflammation go haywire], sepsis [an over-reaction to infection], anaphylactic shock [a severe allergic reaction], these are all examples of inflammation that went way too far in magnitude, so it's induced too strongly.

Again, what is a good magnitude versus too much? The logic of it is decided by evolution.

So one delineation of good inflammation [versus] bad inflammation is just the magnitude of the response.

The second type is when inflammation may be induced in the right magnitude, but it's induced for the wrong reasons. And that is what often leads to chronic inflammation. But the reason that happens is, again, in large part, a mismatch between our evolutionary history and modern environment. [Being obese was uncommon in our evolutionary past], because that would be unheard of under normal, natural conditions where you have to walk for 10 miles to find something to eat every day.

In the modern environment, obesity is common. But that's not what our genes evolved to deal with and they misinterpret it, induce inflammation and then obesity-associated inflammation then becomes a problem.

And the second example of that is aging-associated inflammation. Most of our ancestors throughout history would be dead by 30 years of age. Therefore the body is not, sort of, designed to deal with changes that happen at an advanced age. Many age-related deteriorations in body functions can be interpreted by inflammation as, "oh, something is off, I'm supposed to get in action when something gets off a normal homeostatic [self-regulating] range." And what happens then? It creates this vicious cycle where, [in response to] these deviations that are age-related or obesity-related or [related to] other evolutionarily-new and modern aspects of our lifestyle, inflammation is induced. [The body is] thinking "I will try to fix it." But there's nothing to fix. And that's what is, really, mostly bad inflammation.

Related: DNA-damaging gut bacteria may fuel colon cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease

EC: Is it possible to modulate "bad" inflammation with lifestyle changes, for example with anti-inflammatory diets? Is the evidence actually there?

RM: Yes, it is possible to modulate it. But if you look at the common denominator — so exercise, diet, healthy food, diverse food, avoid processed foods, avoid sedentary lifestyle, have enough sleep, reduce stress — if you think about what is the common denominator, all of them have one thing in common: modify your lifestyle to approximate, slightly better, the way we evolved to be.

EC: From an immunobiology perspective, what message would you want people to know if they were concerned about inflammation?

RM: Well, I would say that inflammation in general is something that we all need to protect ourselves. We don't want to completely eliminate it, that would be lethal basically. Without inflammation we cannot survive. That most causes of unwanted or "bad" inflammation in the modern world, in industrialized countries at least, have to do with aspects of our lifestyles that are unnatural and unhealthy. And I think diet and physical activity are probably the major drivers.

I mean, this is not anything new.

But having said that, there are also conditions that are truly pathological, like autoimmune diseases, for example, or sepsis, and that's where inflammation is mostly evil and mostly just needs to be knocked down and controlled.

But for the majority of people this has to do with chronic inflammation that may be even asymptomatic, sub-clinical, but under the hood slowly contributes to various sorts of unhealthy conditions. And that's where the steps of simple interventions of having the right diet and the right physical activity [come in.]

And I would just add one more thing. Nobody knows what the right diet actually is. I think it's a failure, both on the part of the scientists, and the part of communicators of science. Because if the science is not there, what do you communicate?

And that's that we don't really understand food. We don't understand what a healthy diet is. We don't understand how it affects our bodies. We know some obvious things, trivial things, calories and things like that, vitamins. But beyond that our knowledge is really at the medieval level.

And that, I think, is going to be the next big frontier in biomedical science. So when I say healthy food, healthy diet, I'm just saying it in sort of, in terms of the obvious aspects of it. Eating processed food, highly processed simple sugars, high calorie, unbalanced, those are things that are obviously bad. But beyond those trivial aspects, there is a lot more to it that we don't really understand. So, I say healthy diet, but with the qualification that we only know very little about what a healthy diet really is.

Editor's Note: This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30. (emily.cooke@futurenet.com)