Scientist who discovered body's 'fire alarm' against invading bacteria wins $250,000 Lasker prize

One of this year's coveted Lasker Awards has gone to Zhijian "James" Chen, a scientist behind a key immune-system discovery.

A coveted research award that comes with a $250,000 prize is going to a scientist who helped uncover a protein's role in the human body's immune defenses.

Biochemist Zhijian "James" Chen, director of the Inflammation Research Center and a professor of molecular biology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, has won one of this year's Lasker Awards — biomedical-research prizes often called the "American Nobels."

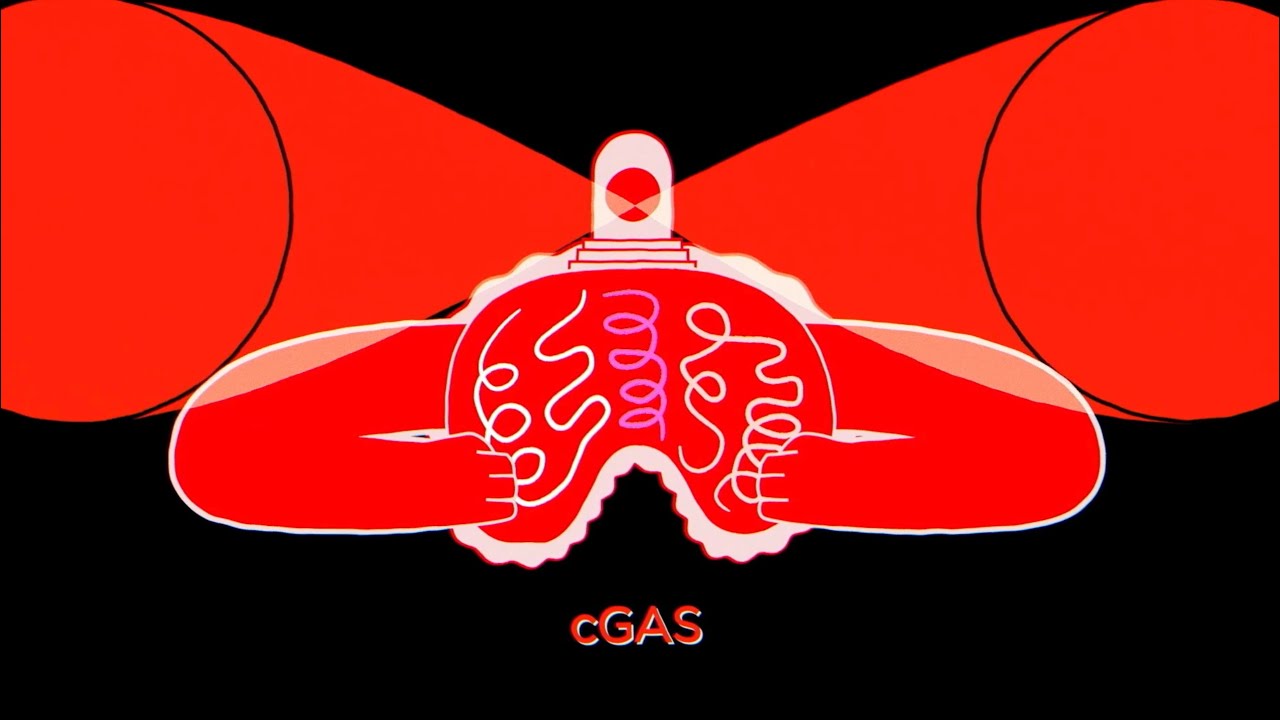

Chen led work that resulted in the discovery of a critical enzyme — cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) — that acts like a fire alarm in the body. But instead of being tripped by smoke, cGAS activates in response to the DNA of foreign invaders, such as viruses and bacteria. Prior to the discovery of cGAS, scientists didn't know how this DNA set off the innate immune system, the body's first line of defense against foreign substances.

Ilya Mechnikov, who won a Nobel in 1908, discovered phagocytosis, a phenomenon in which one cell gobbles up another. This is one way that immune cells rid the body of disease-causing bacteria. In his Nobel lecture, Mechnikov noted that bacterial DNA somehow awakens a "protective army of phagocytes" in the body — but at the time, no one knew how.

Related: Avi Wigderson wins $1 million Turing Award for using randomness to change computer science

Later research, conducted in the early 2000s, revealed that injecting cells with DNA drove a spike in interferons, immune signals that help stop infections. Scientists then uncovered a group of genes that enables the production of these interferons, which they dubbed "stimulator of interferon genes" (STING). STING does not directly sense foreign DNA, but the DNA somehow activates STING nonetheless.

Starting with a paper published in 2012, Chen and his collaborators finally started filling in the missing links in this chain of events. The first is cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP), a molecule that switches on STING when foreign DNA lurks in cells. The second is cGAS, the enzyme that enables the cells of mammals — including humans — to make cGAMP.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the body's early warning system, cGAS is the alarm itself, which detects foreign DNA and calls in reinforcements in the form of cGAMP. In turn, cGAMP recruits the "fire brigade" — which in this case is the innate immune system, including the cells that gobble up invaders.

Chen's group later learned that this system detects not only DNA but also retroviruses, the group of viruses to which HIV belongs. These viruses contain RNA, a genetic cousin to DNA. HIV is a master of evasion when it comes to dodging the innate immune system — but when the virus is detected, it's cGAS that spots it.

Unfortunately, the cGAS alarm system isn't always helpful; in the context of some diseases, it can go haywire.

cGAS plays a role in autoimmune diseases, in which the immune system mistakenly attacks the body. cGAS detects DNA floating around in the fluid of a cell, which is usually a sign of infection. Our own human DNA is typically packaged neatly in compartments called the nucleus and mitochondria — but when a cell falls under stress, that DNA can leak out and end up elsewhere in the cell.

We have enzymes to help break down that escaped DNA, but in some people, these enzymes don't work well. And this deficiency, Chen and colleagues have found, can end up triggering the cGAS alarm system. This hints that cGAS could be key to reining in these harmful immune responses.

"cGAS has been implicated not only in autoimmune conditions, but in numerous inflammatory illnesses, including age-related macular degeneration and neurological disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis," the Lasker Award grantees wrote in a statement. "Calming the cGAS-cGAMP-STING pathway might therefore provide benefit across a broad span of ailments."

Chen was awarded the 2024 Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award.

Two other Lasker Awards were awarded this year — one for clinical research and one for public service. The first went to Joel Habener, Lotte Bjerre Knudsen and Svetlana Mojsov for their discovery and development of drugs that mimic the hormone glucagon-like peptide 1, such as Ozempic, for obesity treatment. The second went to Quarraisha Abdool Karim and Dr. Salim Abdool Karim, whose work has been instrumental in preventing and treating HIV.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.