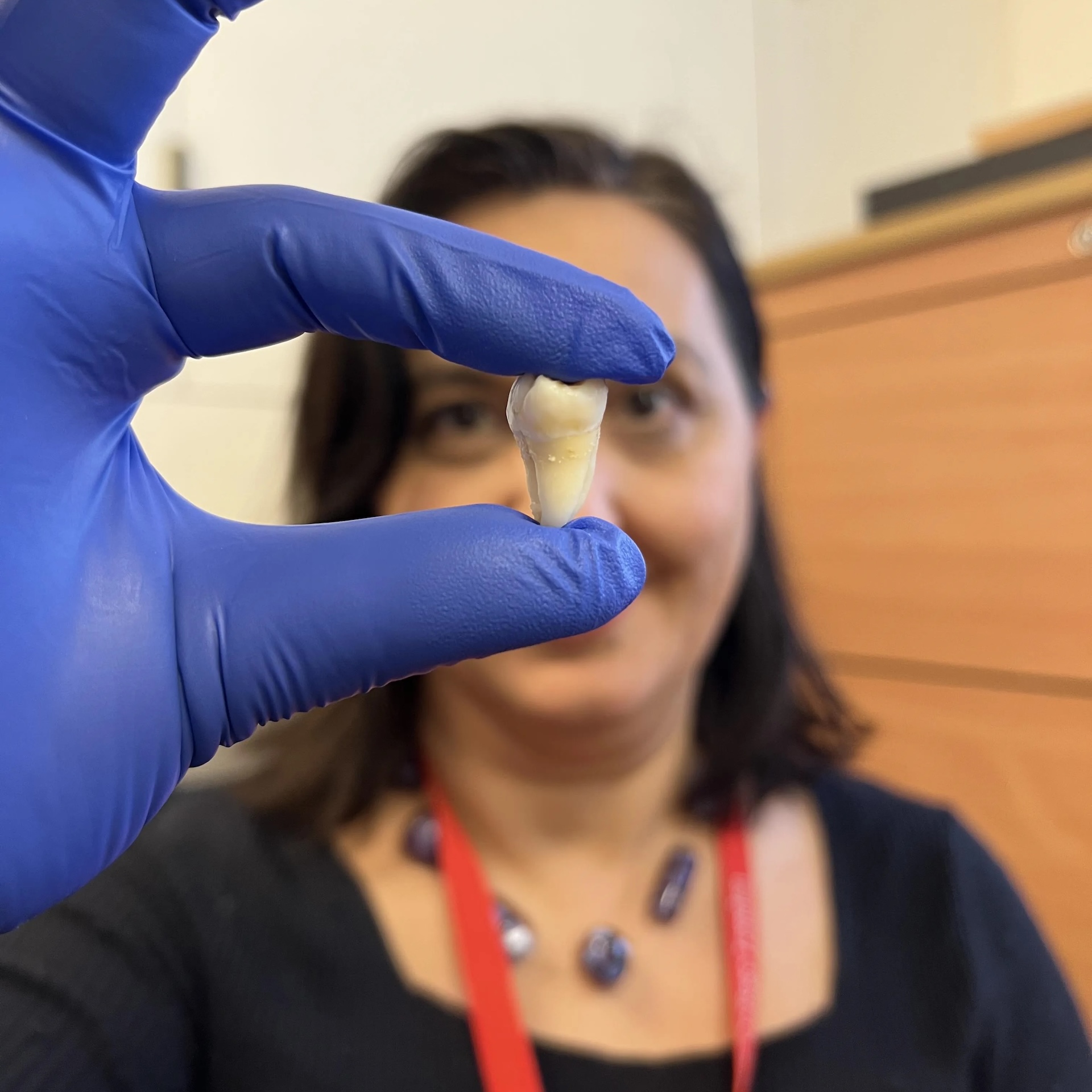

Lab-grown teeth could offer alternative to fillings and implants, scientists say

Scientists in the U.K. have developed a new material that may allow them to grow teeth in the lab, which could provide an alternative to fillings and dental implants someday.

Scientists have gotten one step closer to growing replacement teeth in the lab — a development that could pave the way for new alternatives to unpleasant dental fillings and root canals.

The team developed a special material that allows cells to communicate with one another just as they would in the body, therefore enabling them to develop into tooth cells, the researchers reported in a study published in the journal ACS Macro Letters.

The process allows scientists to grow teeth from a patient's cells in the lab. Someday, it could enable damaged or infected teeth to be replaced by real teeth, rather than being repaired using fillings and other dental procedures.

Humans typically grow two sets of teeth in their lifetime: Around 20 baby teeth start coming in at around 6 months of age and are then gradually replaced by 32 adult teeth starting at about age 6.

Some animals, like sharks or crocodiles, can constantly replace missing teeth, but humans are limited to these two sets. This is because animals that can keep replacing their teeth never lose the tooth stem cells that allow them to constantly grow new teeth. Humans, by contrast, don't retain these active regenerative cells after adult teeth come through.

When our teeth are damaged, dentists mend cavities with fillings or replace teeth with artificial tooth implants. However, these solutions cannot repair themselves and may need to be replaced.

"Fillings aren't the best solution for repairing teeth," study co-author Xuechen Zhang, a researcher at King's College London, said in a statement. "Over time, they will weaken tooth structure, have a limited lifespan, and can lead to further decay or sensitivity."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Related: 9 teeth facts you probably didn't know

Meanwhile, tooth implants require invasive surgery, usually across multiple appointments, and can risk infection and damage to surrounding teeth and gums.

"Both solutions are artificial and don't fully restore natural tooth function, potentially leading to long-term complications," Zhang said.

For years, scientists at King's College London have been working on a process for growing teeth, which involves mimicking how teeth grow within the body. Teeth begin growing from stem cells during early embryonic development, with stem cells from different types of embryonic tissue "talking" to each other using signaling molecules to trigger tooth formation. The stem cells differentiate into various forms of cells, which then secrete the materials that the tooth is eventually made from, such as enamel, dentin and cementum.

In the new study, the researchers described how they made a crucial breakthrough by developing a material that allowed the stem cells to communicate as they would in the body. The material was made from hydrogel — a soft, gel-like material that can absorb large amounts of water — and emulates the environment around the cells in the body, known as the matrix.

"This meant that when we introduced the cultured cells, they were able to send signals to each other to start the tooth formation process," Zhang said. "Previous attempts had failed, as all the signals were sent in one go. This new material releases signals slowly over time, replicating what happens in the body."

Such tooth replacements would be longer-lasting, stronger and much less likely to be rejected by the body, which occurs in between 5 and 10% of tooth implants.

"Lab-grown teeth would naturally regenerate, integrating into the jaw as real teeth," Zhang explained.

The researchers are still far from implanting a replacement tooth into a human patient. Right now, they're working to figure out the best way for a tooth to be introduced into the body.

"We have different ideas to put the teeth inside the mouth," Zhang said. "We could transplant the young tooth cells at the location of the missing tooth and let them grow inside [the] mouth. Alternatively, we could create the whole tooth in the lab before placing it in the patient’s mouth. For both options, we need to start the very early tooth development process in the lab."

Despite these challenges, the development could pave the way for new alternatives to fillings and implants.

"As the field progresses, the integration of such innovative techniques holds the potential to revolutionise dental care, offering sustainable and effective solutions for tooth repair and regeneration," study co-author Ana Angelova Volponi, a researcher at King's College London, said in the statement.

Jess Thomson is a freelance journalist. She previously worked as a science reporter for Newsweek, and has also written for publications including VICE, The Guardian, The Cut, and Inverse. Jess holds a Biological Sciences degree from the University of Oxford, where she specialised in animal behavior and ecology.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.