Deadly motor-neuron disease treated in the womb in world 1st

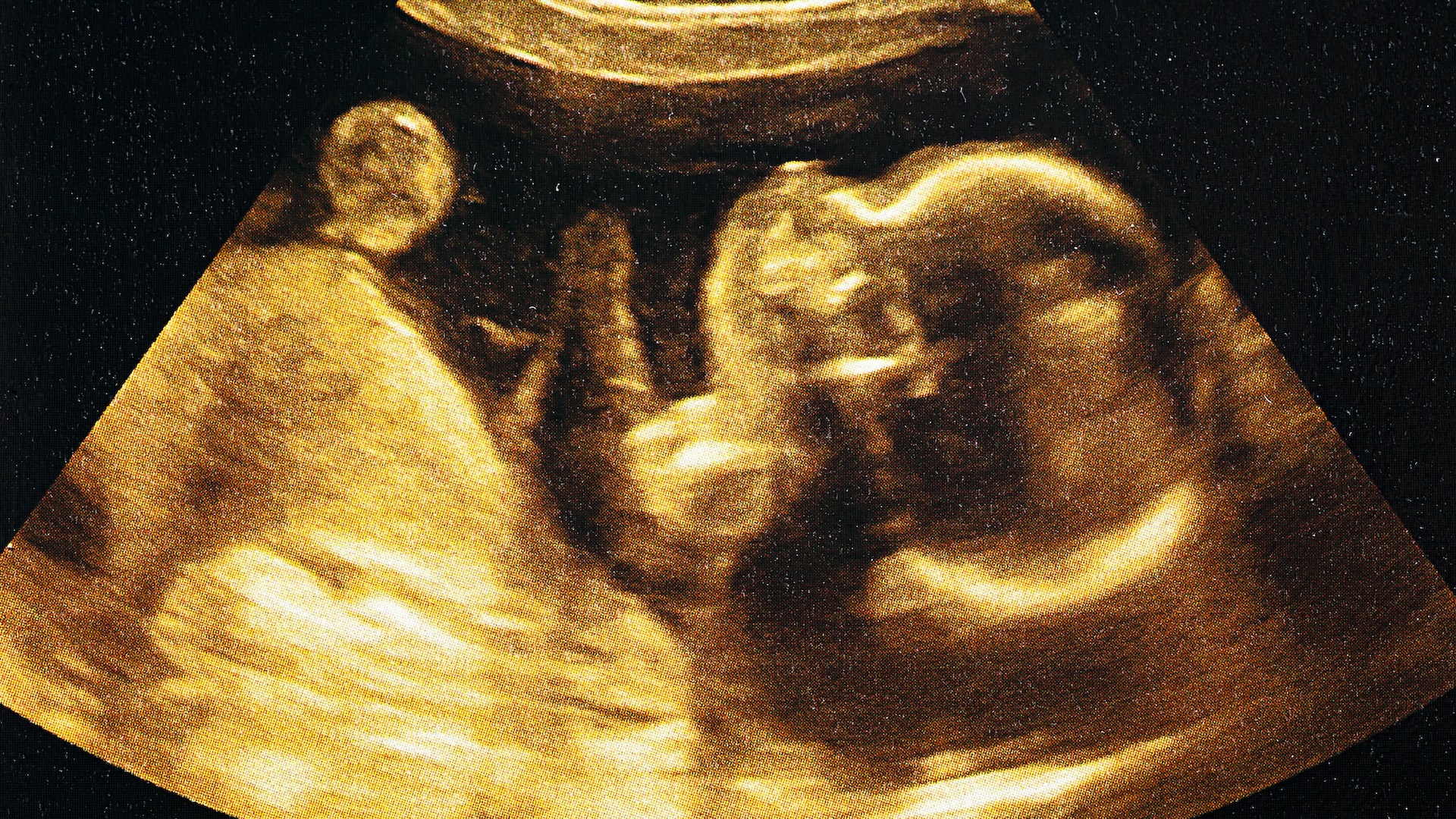

An infant with a fatal genetic disease has survived past the age of 2 with no signs of the condition, thanks to treatment started in the womb.

A child was treated for a rare, potentially deadly genetic disorder while still in the womb — and now, she has survived past the age of 2 with no signs of the condition.

This marks the first time that this condition, called spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), has ever been tackled before birth, according to a new report published Wednesday (Feb. 19) in The New England Journal of Medicine. The child in this case specifically had SMA type 1, the most common form of the disorder; it has a very poor prognosis, typically leading to death before a child's second birthday.

The "baby has been effectively treated, with no manifestations of the condition," Dr. Michelle Farrar, a pediatric neurologist at the University of New South Wales Sydney in Australia who was not involved in the study, told Nature News.

SMA is an inherited condition that affects specific motor neurons, namely the nerve cells in the spinal cord that control the voluntary movement of our muscles. Over time, SMA eventually leads to the weakening and wasting away of the muscles. It's estimated to affect around 1 in every 10,000 live births.

Related: The exceptionally rare disease that causes holes to form in your brain

The condition is usually caused by mutations in a gene called SMN1, which contains instructions for how to make a protein called survival motor neuron (SMN) protein. This protein is critical for motor neurons to make proteins and grow the "wires" that send signals out to the muscles.

When the SMN1 gene is mutated, the body cannot make enough SMN protein, and the nerves cannot adequately send out signals to muscles. As a result, the muscles — especially in the thighs, back, shoulders and hips — begin to weaken and shrink from disuse and a lack of nerve stimulation.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The severity of these symptoms differs depending on the type of SMA a person has. There are five types of SMA linked to SMN1 gene mutations, classified by symptom severity and by how early the symptoms appear. Earlier onset symptoms — which show up before or shortly after birth — typically lead to worse survival outcomes. Infants with SMA type 1, which manifests within six months after birth, develop severe weakness that causes difficulty breathing and swallowing, and they often die within the first few years of life without treatment or breathing support.

SMA type 1 is the leading genetic cause of infant death.

The infant involved in the recent case was found to be at risk for SMA type 1 after undergoing genetic testing in the womb. The parents had already had one child with confirmed SMA type 1 who had previously passed away. The tests revealed that the growing fetus also had mutations in the SMN1 genes on both chromosomes.

The drug risdiplam (brand name: Evrysdi) is one of three treatments approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of SMA in infants. A tablet taken by mouth, it causes the body to boost the activity of a second gene, called SMN2, which also carries the instructions for building SMN protein but typically makes less than SMN1.

Until now, this drug had only been administered after birth, but in this case, the drug was given to the fetus in the womb upon request from the parents.

"They had already experienced a loss from this horrible disease," study lead author Dr. Richard Finkel, a clinical neuroscientist at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, told Nature News. Risdiplam is approved for children who are at least 2 months old, so the FDA gave special clearance for the drug's early use.

At 32 weeks of pregnancy, the mother started taking risdiplam daily for six weeks. Testing at the time of birth indicated that the drug had indeed been entering the baby's system while in the womb. Roughly one week after birth, the baby herself was given the drug orally.

At birth, the infant was found to have higher levels of SMN protein and less nerve damage than other babies born with SMA type 1. In the months since her birth has shown no signs of abnormal muscle development.

"That's obviously very reassuring," Finkel said.

The child will likely have to take risdiplam for the rest of her life, into adulthood, and she will be closely monitored for any changes in her muscle development.

The researchers noted that this result is based on only a single case, but despite this, these findings indicate that SMA and other genetic conditions might be more effectively tackled if treatment is started before birth. They hope to investigate if these results can be replicated in larger studies in the future.

Disclaimer

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Jess Thomson is a freelance journalist. She previously worked as a science reporter for Newsweek, and has also written for publications including VICE, The Guardian, The Cut, and Inverse. Jess holds a Biological Sciences degree from the University of Oxford, where she specialised in animal behavior and ecology.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.