Designer immune-cell therapy could shrink deadly brain tumors, early trials show

Two early clinical trials that together included nine patients suggest that a treatment called CAR-T therapy could treat glioblastoma, but its long-term effects are unknown.

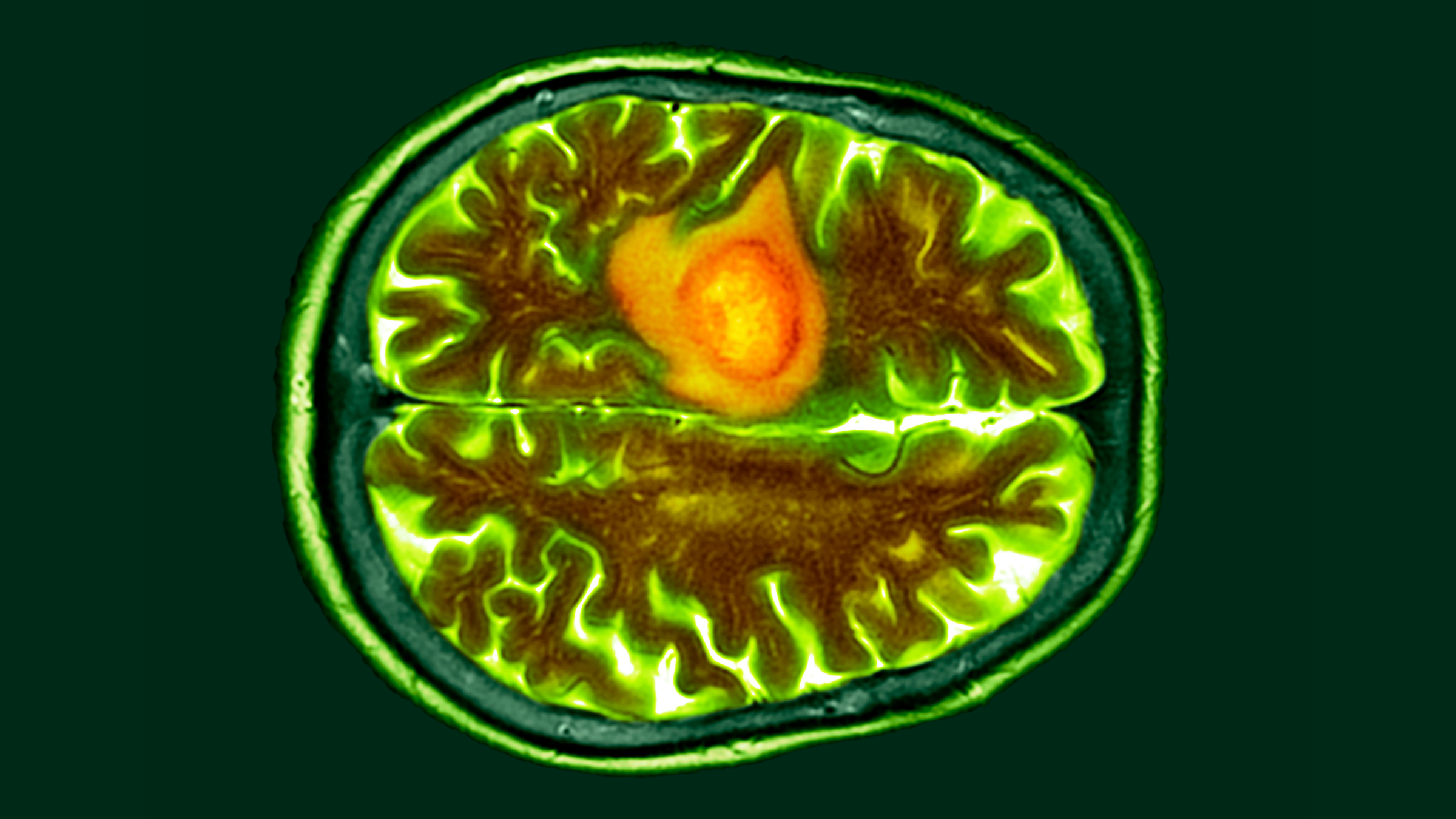

A new immune cell-based treatment for glioblastoma, the most aggressive type of brain cancer, has shown promise in shrinking tumors in the short-term, according to two early clinical trials.

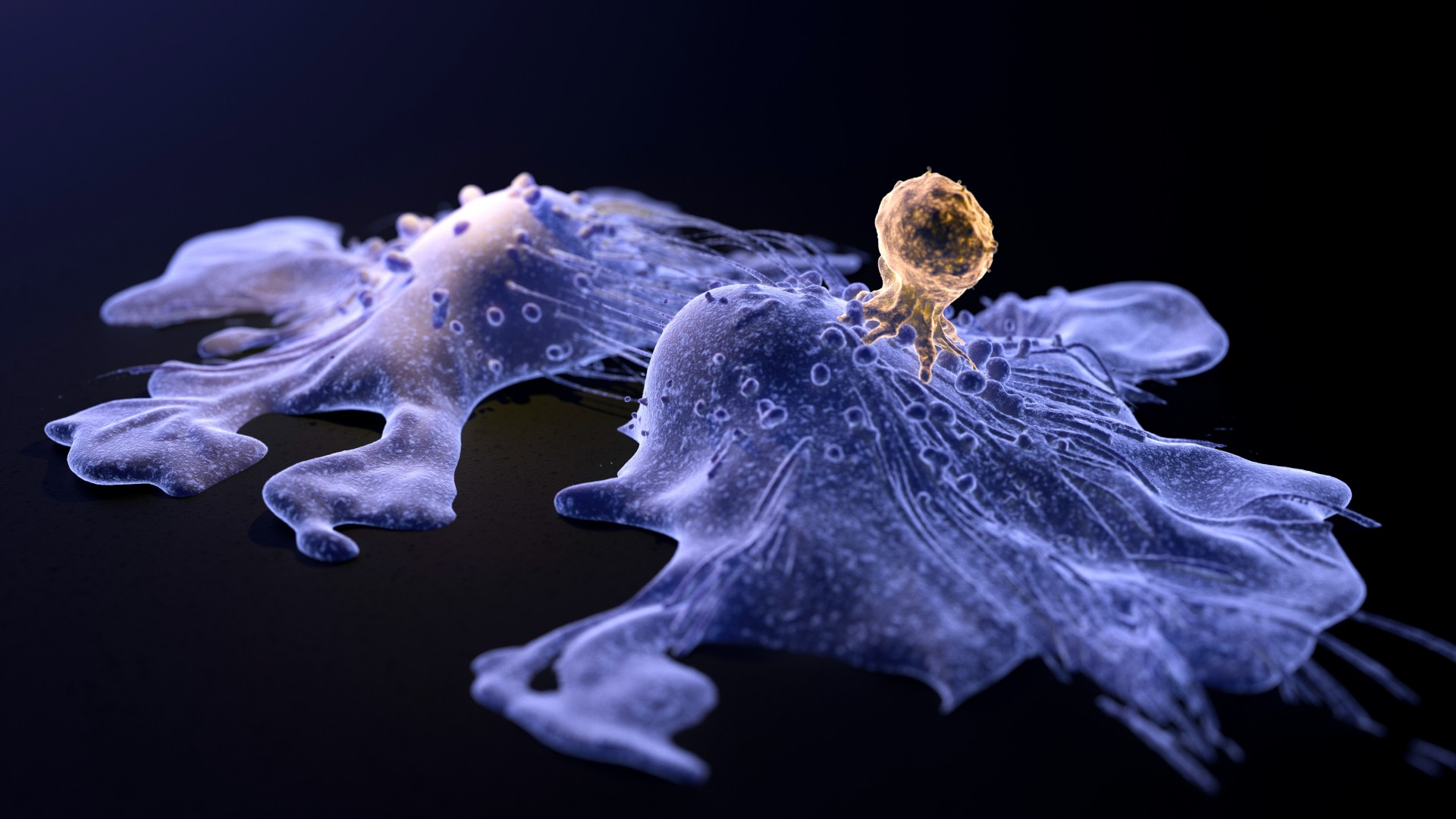

The trials tested the safety and effectiveness of a personalized therapy called chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy. This involves drawing out and genetically manipulating patients' immune cells, known as T cells, to more effectively recognize and attack tumors once they're reintroduced into the body.

One of the trials, described in a paper published Wednesday (March 13) in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), included three patients with recurrent glioblastoma, meaning their cancer had returned following standard radiation and chemotherapy. T cells from these patients were genetically modified to target two versions of a receptor called epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) on the surface of tumor cells.

In the second trial, published the same day in the journal Nature Medicine, researchers used CAR T cells to target EGFR and an additional tumor-related receptor, called interleukin-13 receptor alpha 2, in six patients with recurrent glioblastoma.

Related: In a 1st, scientists use designer immune cells to send an autoimmune disease into remission

Both trials found that CART-cell therapy was safe and reduced tumor size in all nine patients. In the Nature Medicine study, patients saw these reductions within one or two days, while in the NEJM study they saw them after one to five days. One NEJM patient's tumor almost completely regressed five days after a single treatment, while another person's tumor decreased in size by 60.7% after 69 days.

However, these effects didn't necessarily last. Tumors returned for two patients in the NEJM study, within either 72 days or a month after the initial infusion. The other patient showed no signs of tumor recurrence more than 150 days after treatment, although this was the last assessment point of the study so it is uncertain whether this occurred afterward. Some of the reductions seen in the Nature Medicine study have also been sustained for several months, for example up to seven months in one patient.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Glioblastomas are notoriously difficult to treat, usually relying on surgery to remove them as well as chemotherapy and radiation to kill the cancerous cells. Each year, more than 10,000 people in the U.S. are diagnosed with glioblastoma. Only 6.9% of them survive beyond five years after diagnosis and most live for only another eight months.

The new CAR T-cell therapy is still in its early days, with no data yet available on the long-term survival rates of these patients. Nevertheless, scientists believe there is reason for optimism.

The research "lends credence to the potential power of CAR-T cells to make a difference in solid tumors, especially the brain," Dr. Bryan Choi, lead author of the NEJM study and a brain-tumor surgeon at Massachusetts General Hospital, told Nature. "It adds to the excitement that we might be able to move the needle."

CART-cell therapy has been approved in the U.S. to treat blood cancers, such as lymphomas, some forms of leukemia and multiple myeloma. However, scientists have struggled to develop the therapy for solid tumors, such as glioblastoma, as the cells within them often vary in their characteristics, meaning they have more ways of evading the immune system.

The new treatments target receptors that are commonly expressed by glioblastoma cells, thus singling them out for destruction. The NEJM study also manufactured T cells that can produce antibodies against these receptors, giving them a second mode of attack. More data is required to evaluate the longer term effects of these new treatments, and trials will need to be conducted in larger, more diverse groups of patients to determine their broader relevance.

"These results are exciting, but they are also just the beginning — they tell us that we are on the right track in pursuing a therapy that has the potential to change the outlook for this intractable disease," Dr. Marcela Maus, co-senior author of the NEJM study and director of the Cellular Immunology Program at the Mass General Cancer Center in Massachusetts, said in a statement.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30.