Assuming the worst in others can be 'read' in brain scans

Activity in the brain's "ventromedial prefrontal cortex" differs between people who assume the worst in social situations and those who don't, a study finds.

The brain activity of people who are easily offended is different from that of people who aren't as prone to getting riled up, a new study suggests.

Many people would consider a missed text from a best friend to be a harmless, accidental act. Maybe they're busy, or perhaps they read it and simply forgot to reply. However, some people are more likely to misconstrue this action as aggressive or hostile, thinking they're perhaps ignoring you on purpose. Scientists call this tendency to assume the worst in people "hostile attribution bias," and it can make people more likely to be aggressive, experience poor mental health and struggle to maintain healthy relationships.

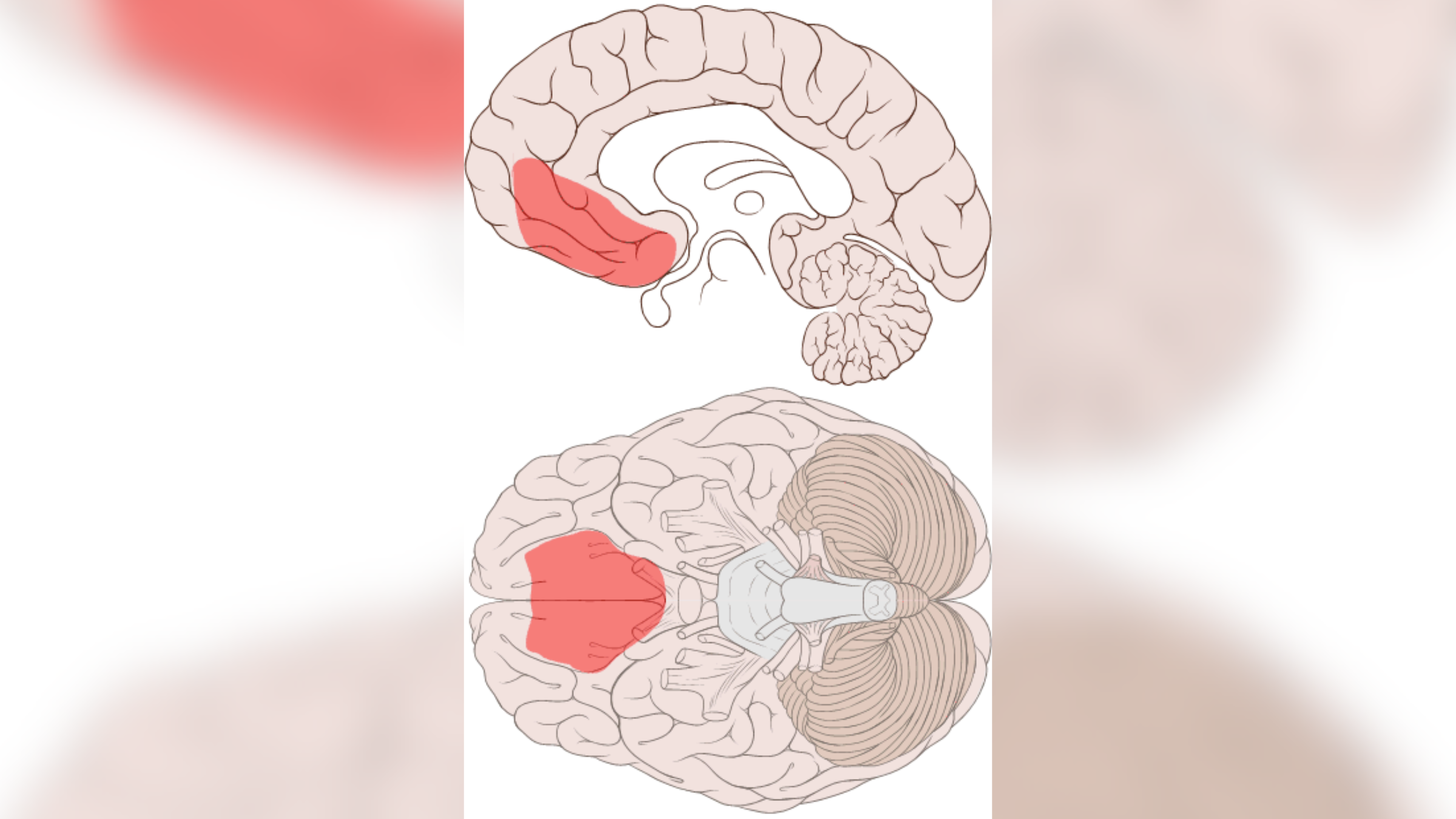

A new study suggests that people with hostile attribution bias display a unique signature of brain activity in part of the brain called the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) when another person's actions result in a negative outcome for them. Among other functions, the vmPFC is involved in emotional regulation, decision-making and self-perception.

"The VmPFC is a high-order brain region that integrates sensory information about the external world with internal states and beliefs," Yuan Chang Leong, co-senior study author and an associate professor of psychology at the University of Chicago, told Live Science in an email. In other words, the vmPFC helps control how we react to social situations based on our already established biases.

Related: Neuralink chip implanted into human brain for the 1st time, Elon Musk says

The results of the new study, published Monday (Feb. 5) in The Journal of Neuroscience, suggest that the vmPFC plays a role in governing a person's interpretation of a social situation by integrating information about the unfolding scenario with their preconceived notions and memories, Leong said.

Understanding the brain mechanisms behind hostile attribution bias could bring scientists a step closer to developing ways of mitigating it — for example, through more targeted interventions to reduce aggressive behavior and promote healthier relationships, the authors wrote in the paper.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the study, 58 volunteers listened to audio recordings of people describing 21 hypothetical social scenarios. On average, the mini-podcasts were around 40 seconds long and involved a character executing actions toward the listener — the study participant — that could have a negative effect on them. For instance, in one scenario, a professor forgot to write a letter of recommendation for the participant after they'd agreed to do so.

After listening, the participants rated whether they thought these actions were intentional and hostile — for example, the professor was purposefully retaliating against them — or unintentional, meaning they simply forgot to write the letter.

Throughout the experiment, each participant wore a fitted cap on their head that measured their brain activity using a technique called functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS). The researchers found that, during the recordings, fluctuations in brain cell activity in the vmPFC was similar among individuals with similar levels of hostile attribution bias and differed in those without the tendency.

This suggests that this bias has steadily shaped how their brains respond to such scenarios, driving the activity to look the same, Leong said. Using the brain-activity readouts, the authors could predict with 75% accuracy whether someone had low or high hostile attribution bias, based on the pattern of activity in their vmPFC.

The authors also found that participants who exhibited less hostile attribution bias scored higher on a survey that assessed another psychological concept, called attribution complexity. This measures how likely someone is to consider that there may be many complex explanations for certain behaviors.

As such, "fostering attributional complexity could be a potential strategy to mitigate hostile attribution bias and ultimately promote healthier social interactions," the authors wrote in the paper.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30. (emily.cooke@futurenet.com)