Is there really a difference between male and female brains? Emerging science is revealing the answer.

Brain scans, postmortem dissections, artificial intelligence and lab mice reveal differences in the brain that are linked to sex. Do we know what they mean?

You're holding two wrinkly human brains, each dripping in formaldehyde. Look at one and then the other. Can you tell which brain is female and which is male?

You can't.

Humanity has been hunting for sex-based differences in the brain since at least the time of the ancient Greeks, and it has largely been an exercise in futility. That's partly because human brains do not come in two distinct forms, said Dr. Armin Raznahan, chief of the National Institute of Mental Health's Section on Developmental Neurogenomics.

"I'm not aware of any measure you can make of the human brain where the male and female distributions don't overlap," Raznahan told Live Science.

But the question of how male and female brains differ may still matter, because brain diseases and psychiatric disorders manifest differently between the sexes. Disentangling how much of that difference is rooted in biology versus the environment could lead to better treatments, experts argue.

There are many different disorders of the brain — psychiatric and neurologic diseases — that occur with different prevalence and are expressed in different ways between sexes, said Dr. Yvonne Lui, a clinician-scientist and vice chair of research in NYU Langone's Department of Radiology. "Trying to understand baseline differences can help us better understand how diseases manifest."

Now, thanks in part to artificial intelligence (AI), scientists are starting to reliably distinguish male and female brains using subtle differences in their cellular structures and in neural circuits that play a role in a wide range of cognitive tasks, from visual perception to movement to emotional regulation. Other studies point to sex-based differences in human brain structure that may be present from birth, and still other, lab-based research in animals points to sex-based differences in how brain cells fire at a molecular level.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

What's still completely unclear is to what extent these differences matter. Do they change how people's brains function or how susceptible they are to disease? Should they dictate which treatments doctors offer to each patient? Even as scientists pinpoint subtle brain differences between females and males, their research inevitably runs up against tricky questions of how sex, gender and culture interplay to sculpt human cognition.

Right now, it's impossible to answer these big questions. But ongoing and future research — focused on lab animals, human chromosomes and brain development, and subjects followed from youth through adulthood — could start to reveal how these sex-based differences concretely affect cognition, and ultimately, the development of diseases of the brain.

Why study sex-based brain differences?

Historically, scientists used purported brain differences to make sweeping statements about how men and women think and behave and to justify sexist beliefs that women were innately less intelligent and less capable than men.

While that early research has been discredited, modern studies still find cognitive differences between men and women — at least on average. For example, men reportedly perform better on tests of spatial ability, while women are better at interpreting the facial expressions of others. But men and women are raised and treated very differently in society, so what's at the root of these differences? Is it nature or nurture, or both?

"It's actually incredibly difficult in humans to … causally distinguish how much of a sex difference is societally or environmentally driven," Raznahan said. "We have all of these assumptions and biases that sort of slip into our heads through the back door without us realizing."

Given the dubious history of studying sex differences in the brain, and the logistical difficulty of doing it the right way, one might wonder why scientists bother. For many, it's because neurological diseases and psychiatric conditions seem to play out differently in males and females, and both biological and environmental factors could explain why that is.

Data suggest women experience higher rates of depression and migraine than men do, while men have higher rates of schizophrenia and autism. About twice the number of men develop Parkinson's disease than women do, but women with the condition tend to have faster-progressing disease. All these data come from studies that don't necessarily distinguish sex from gender — "sex" describes biology, while "gender" reflects self-identity, as well as societal roles and pressures. Lumping the two concepts together muddies our understanding of why a given difference exists.

For instance, pubescent girls are more likely to experience depression than boys are, which may be related to how their maturing brains handle stress or the possibility that they encounter more stressful events than boys do at that age. Conversely, do boys' brains make them resilient against depression, or are they actually going underdiagnosed due to social stigma? The answers to these questions point to different solutions.

Large-scale structures, negligible differences

Thanks to brain-scanning techniques like MRI, scientists have found subtle sex differences in the size, shape and thickness of various brain structures, as well as differences in networks that link different parts of the brain.

But these differences are small to negligible when you account for the average size difference between males and females, argues Lise Eliot, a professor of neuroscience at the Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science and author of "Pink Brain, Blue Brain" (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009).

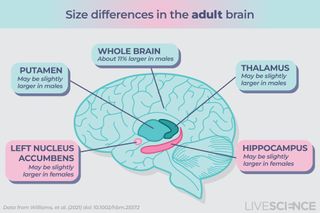

Eliot and colleagues recently looked at about 30 years of studies, finding that, on average, male brains are 6% larger than female brains at birth and grow to be 11% larger by adulthood. This makes sense because average brain size scales along with average body size, and male bodies tend to be larger. But when you take this overall size difference into account, subtler structural differences between male and female brains shrink to the point of negligibility, the researchers concluded.

"There are maybe species-wide sex differences in the brain, but so far, they haven't been proven," Eliot told Live Science. "And so if they exist, they must be pretty small."

Nonetheless, some scientists have reported differences that they say don't scale with body size. Some examples came from a research group who'd crunched MRI data from over 40,000 adult brains scanned for the UK Biobank, a repository of medical data from 500,000 adults in the United Kingdom.

In that study, males had a larger thalamus, a relay station for sensory information. They also had a larger putamen, which helps control movement and forms part of a feedback loop that tells you whether a movement was well executed. Females, on average, had a larger left-side nucleus accumbens, part of the brain's reward center, and a bigger hippocampus, the storage site for short-term memories of facts and events that also helps transfer the information to long-term memory.

But neither this nor other studies have revealed a specific feature that reliably distinguishes a given male brain from a female brain, since the size ranges seen in each sex largely overlap, Raznahan and colleagues noted in a letter responding to that study.

For the few size differences that do exist, it's currently impossible to say whether they explain any differences in cognition linked to sex, or alternatively, whether they actually make males' and females' cognition more similar, the letter authors noted. Perhaps male and female brains operate slightly differently to reach the same output — to "counterbalance" differences in hormones or genetics that may affect brain function, they wrote.

"When we're just talking about describing a difference in a measurement, that's not saying anything about whether it's got any functional relevance at all," Raznahan emphasized.

AI finds subtle differences

While large-scale structural features might not distinguish male and female brains, AI is helping to uncover other, subtler features that may differentiate the two. Some of these differences appear on the level of the brain's microstructure, meaning its individual cells and components of those cells.

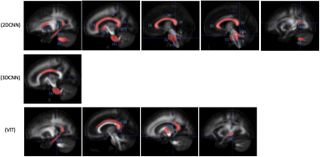

For instance, a study published in May 2024 used different AI models to analyze brain scans from 1,030 young adults ages 22 to 37 years old. The research primarily focused on white matter, the bundles of insulated wiring that run between neurons. "I believe ours is the first study to detect brain microstructural differences between sexes," said Lui, who co-authored the study.

The AI models analyzed differences in both local landmarks in the brain — such as the corpus callosum, which connects the brain's two halves — and the highways that connect distant cells. It also looked at differences in how the white matter was bundled together, as well as in how dense and well insulated those bundles were.

The algorithms accurately predicted the sex of the subject tied to a given scan 92% to 98% of the time. That remaining gap in accuracy likely comes down to the "huge amount of variance in humans," Lui said.

No single part of the brain could be used to make predictions; one model relied on 15 distinct regions of white matter. All models showed some consistencies, though, with the largest white matter structure that crosses the midline, the corpus callosum, standing out as key.

From birth

Lui and colleagues' study was not designed to address how an individual's upbringing or environment shapes the brain. Nor did it aim to disentangle biological differences in the brain from those rooted in gender.

Sex describes biological differences in anatomy, physiology, hormones and chromosomes. Sex traits are categorized as male or female, although some people's traits don't fit neatly in either category. Gender, on the other hand, is cultural. It encompasses how people identify and express themselves, as well as how they are treated and expected to behave by others. Genders include man and woman, as well as others, including those that fall under the umbrella term nonbinary or are unique to specific cultures, like the māhū of Hawai'i.

Historically, studies have conflated sex and gender. To tease these factors apart and see how each manifests in the brain, it would be helpful to follow people over time as their brains are developing — and new research is beginning to do just that.

For example, a 2024 study looked at average brain volume in over 500 newborns: Males' brains were 6% larger overall, even after accounting for differences in birth weight, and females had larger gray-to-white matter ratios. (Gray matter, the cell bodies of neurons, is primarily found in the outer layer of the brain, called the cortex.) That average difference in gray matter is also seen in adults, which makes sense given that larger brains need more white matter to relay signals between far-apart cells.

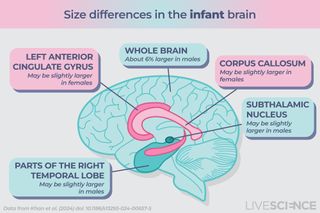

Statistically, these big-picture brain differences were more significant than differences seen in smaller structures. Females had larger corpus callosa, as well as more gray matter around the hippocampus and in a key emotion-processing hub called the left anterior cingulate gyrus (ACG). Males had more gray matter in parts of the temporal lobe involved in sensory processing, as well as in the subthalamic nucleus, key for movement control. But sex could only explain a fraction of the variance seen in these structures.

Some of these brain differences are "present from the earliest stage of postnatal life" and persist into adulthood, the authors noted. This applies mostly to the global differences, but also potentially to some of the smaller ones. For example, some studies — but not all — show that the left ACG is also larger in adult females, not only in babies.

Durable differences present from birth are likely sex-based. But differences that emerge or disappear in later life, like those in the hippocampus, may be influenced by the environment, or else reflect sex differences in development, including hormonal shifts in puberty.

Gender and sex

Studies like this can help tease apart the influence of sex and gender on the brain. At present, there's a "massive gap" in our understanding of how these factors shape the brain independently and in tandem, said Elvisha Dhamala, an assistant professor of psychiatry at the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research in New York.

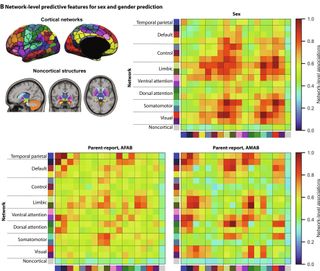

Dhamala and colleagues recently aimed to fill in that gap using data from the Adolescent Brain and Cognitive Development (ABCD) study, an enormous U.S.-based study of brain development and child health. They incorporated functional MRI (fMRI) scans from nearly 4,800 children; fMRI tracks blood flow in the brain to give an indirect measure of brain activity. Each child joined the study at age 9 or 10 and will be followed for 10 years, which will enable follow-up studies.

The fMRI scans highlighted linked brain areas, or networks that lit up as the children did different tasks, including memory tests that required them to recall several images. The children and their parents also answered questions about the kids' feelings about their genders and how they typically play and express themselves. "It's not anything clinical," Dhamala noted. "It's just an aspect of behavior that represents your gender."

These answers were used to generate "scores" for each child that the AI algorithm could use as data points.

The algorithm ultimately revealed two largely distinct brain networks tied to sex and gender. The brain differences most strongly tied to sex were found in networks responsible for processing visual stimuli and physical sensations, controlling movement, making decisions and regulating emotions. Differences tied to gender were more widely dispersed, involving connections within and between many areas in the cortex.

After pinpointing these networks, the researchers trained their AI algorithms to "predict" a child's sex or gender based on brain activity. They accurately determined most children's sexes, similar to the results of Lui's study. Gender proved trickier: With the children's questionnaire answers, the AI couldn't predict where they landed on a continuum of gender, whereas with the parents' answers, its predictive power exceeded chance but was still "much lower" than the predictions for sex, Dhamala said.

Nonetheless, the study highlighted an understudied idea: that gender sculpts the brain in ways that are distinct from sex, she said.

Interestingly, some tentative lines can be drawn between Lui's and Dhamala's AI-powered studies. They can't be directly compared, as the two studies used different types of analyses and focused on different features of the brain. But many of the physical white matter tracts flagged in the former study correspond with functional networks highlighted in the latter, Dhamala told Live Science.

As an example, the cingulum — a white-matter tract that encircles the corpus callosum — seemed key for making predictions in Lui's study. It also links together various networks flagged in Dhamala's study, including circuits involved in emotional processing. That hints that sex differences exist in both the physical anatomy of these networks and in their activation patterns, Dhamala said.

The future of the sex-difference field

Scientists have made some progress at teasing out sex differences in the brain, but to truly understand these distinctions, researchers will need to do more animal studies to allow for more experimental control, according to a 2020 paper co-authored by Raznahan.

Various studies in lab rats have already revealed differences in how males and females form connections between neurons, and how each sex processes fearful memories, for example.

In humans, scientists can collect more brain data right at the time of birth, to pinpoint baseline differences that might exist before a child encounters any cultural influences, and then track the child over time, Raznahan and colleagues added.

Another option is to study human genes that are unique to either the X or Y chromosome. By looking at people with extra or missing sex chromosomes, for example, scientists have started to unravel how these genes either inflate or shrink brain structures, contributing to sex differences in size. Chromosomes may also raise or lower the risk of disorders — for instance, carrying an extra Y raises the likelihood that a person has autism, whereas an extra X does not. That may help to explain why males, who usually carry one X and one Y, have higher autism rates than females, who typically have two Xs.

Right now, the fate of such research is uncertain in the U.S.

Prompted by executive orders from the new presidential administration, the National Science Foundation has been combing through active research projects to see if they include words that might violate said orders, such as "woman," "female" and "gender," and the National Institutes of Health appeared to archive a long-standing policy requiring both male and female lab animals in studies.

"There's just a lot of uncertainty," Dhamala told Live Science. If the worst case scenario comes to pass, "removing that gender component, or making it harder to study sex differences, is going to push us backward rather than forward."

But if the field survives, future work could incorporate gender the way the ABCD study did, using questionnaires to generate composite scores, Dhamala said. As a start, scientists could at least ask study participants what gender they identify as, she added. Other experts agree.

By adopting these strategies, scientists could dramatically advance this research field that dates back to Aristotle. Their efforts could lend new talking points to the endless debate of nature versus nature. They could uncover meaningful sex differences that pave the way to better treatments for depression, Alzheimer's and more. Or they could highlight the ways members of the "opposite sex" are actually more alike than they are different.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.