Men have a daily hormone cycle — and it's synced to their brains shrinking from morning to night

A month-long study of a man's brain revealed that its volume consistently shrunk over the course of each day and then reset overnight.

The daily ebb and flow of hormones in the male body may play a role in shrinking the brain throughout the day, a study hints. After losing volume between morning and evening, the brain resets overnight, starting the cycle again, the research shows.

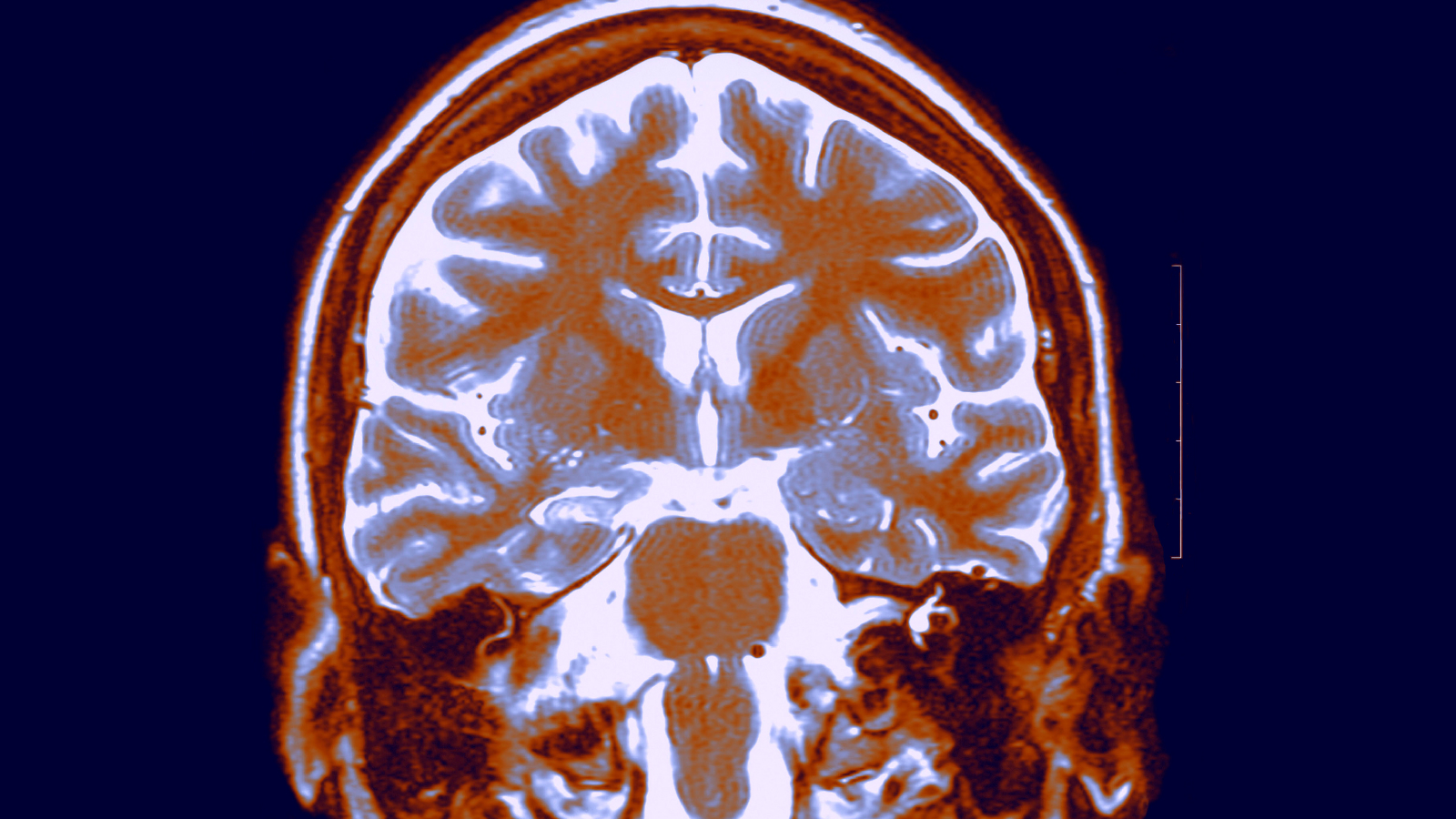

The study involved scanning a 26-year-old's brain 40 times in 30 days. Each magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan was collected at either 7 a.m. or 8 p.m., which is when levels of steroid hormones — namely, testosterone, cortisol and estradiol — are at their highest and lowest, respectively.

"Males show this 70% decrease from morning to night in steroid hormones," said study co-author Laura Pritschet, who's now a postdoctoral scholar in psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine. The degree of change between morning and night narrows with age, but that general pattern persists throughout life.

"You can think of it almost like a pulsating rhythm from morning to night," Pritschet told Live Science. Females also experience a daily flux in hormones, but it's not as pronounced, she noted, because the menstrual cycle is simultaneously driving longer-term shifts in hormones.

Related: Pregnancy shrinks parts of the brain, leaving 'permanent etchings' postpartum

The new study revealed that, throughout the day, the subject's overall brain volume decreased, as did the thickness of the cortex, the brain's outer layer. The volume of gray matter, which contains the cell bodies of neurons and the connections between them, fell by an average of about 0.6%.

Two regions of the cortex, known as the occipital and parietal cortices, shrank the most. Changes were also seen in deeper brain structures, including the cerebellum, brainstem and parts of the hippocampus. These parts of the brain are respectively involved in coordinating movement; relaying information between the brain and body; and storing memories.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The decline in brain volume parallels the daily decline in hormones. However, it's not yet clear whether the hormones drive the brain changes, the study authors wrote in a report published Wednesday (Sept. 18) in The Journal of Neuroscience.

I like the counterpoint that we are now highlighting the ways in which men's endocrine systems are variable.

Pavel Shapturenka, the study's subject

"I think that's an open question," study co-author Elle Murata, a doctoral student in psychology and brain sciences at University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB), told Live Science. But nonetheless, "this is, I think, another example debunking the myth that hormones are only relevant for females."

Past research suggests that steroid hormones shape the brain. The menstrual cycle has been linked to volume changes across the whole brain, and studies suggest those changes don't happen when the hormonal cycle is altered — for example, by birth control. Decades of animal studies also suggest that steroid hormones shape brain structure on short timescales.

"I'm convinced that hormones impact the brain and brain structure," Murata said. "But in this study, we can't say that it's directly causing it."

Could males' hormonal circadian rhythm be affecting brain function? For now, it's unclear exactly how it might be doing so. That said, a different study by the team suggests there are changes in the brain's connectivity that follow a 24-hour cycle.

In that other study, the team probed the same individual but looked at the patterns of communication between different parts of the brain, rather than taking snapshots of its structure. The researchers found that "coherence" — a measure of synchronization — across the brain rose and fell along with the levels of steroid hormones.

Interestingly, brain regions that process visual information cropped up in both studies, Murata noted. These brain areas showed both a loss of volume and a loss of coherence throughout the day.

"Maybe something is happening in the visual networks," Murata suggested. "The jury is out as to why that may be." It's also key to note that this pattern was seen in only one person's brain, and different patterns may emerge in different people.

The subject of the current studies, Pavel Shapturenka, told Live Science that he found the brain-scanning process "relaxing," in an almost "hypnotic" way. When asked why he volunteered for the research, he said it was a "unique opportunity" to contribute to an area of neuroscience that we don't know much about. (Shapturenka and Pritschet are married and were both doctoral students at UCSB during the study's data collection, although Shapturenka studies chemical engineering rather than brain science.)

"All the information that's out there highlights the inherent endocrine [hormonal] variability in women," said Shapturenka. "I like the counterpoint that we are now highlighting the ways in which men's endocrine systems are variable," especially since that variability might affect brain function, he said.

Pritschet and Murata said that a next step might be to investigate how differences in sleep change these dynamics in the brain. Sleep disruptions are tied to metabolic diseases and mental health conditions, so it would be interesting to see how the brain's daily cycle fits into that picture. The brain's garbage disposal — called the glymphatic system — also comes online during sleep and may therefore have its own role to play in this daily cycle, they said.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.