Monkey study reveals science behind 'choking under pressure'

When a person (or monkey) is facing stakes that are too high, the stress can interfere with neurons, affecting how they direct the body to execute movements, a study suggests.

When people "choke under pressure," it's often at times when success could result in a big payoff — maybe they're an athlete at a championship match or an actor performing for a renowned director. Now, a study in monkeys could help reveal why: The prospect of a large reward can interfere with brain signals that prepare us for a given task, leading to underperformance.

The study, published in the journal Neuron Sept. 12, involved three monkeys completing tasks to get a reward — in this case, water to drink. The primates performed their best when the prize at stake was a medium to large volume of water. But when they could win an unusually large "jackpot," they underperformed, or choked under pressure.

The task was a test of speed and accuracy, in which the monkeys were trained to reach for a target on a screen. The monkeys had to wait for a cue to begin reaching and then hold that position for a time. The color of the cue corresponded with the size of their potential reward for doing so accurately, from small to jackpot.

Before running the official experiment, the scientists checked that the monkeys learned the value of each reward and found that they could identify the larger of two rewards about 99% of the time.

Related: Can you 'catch' stress from other people?

During the experiment, the scientists tracked the activity of hundreds of cells in the monkeys' brains, using implanted electrodes. The cells were known to be involved in "motor preparation," in which the brain prepares to execute a motion, like reaching with a hand.

The monkeys performed the worst when the prize was either too small — in which case they reached for the target carelessly — or too large — in which case they seemed overly cautious.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"They were too slow," said first study author Adam Smoulder, a doctoral student at Carnegie Mellon. "It was as if they were worried about missing the target … and focusing so much on what they were doing that they'd run out of time," Smoulder told Live Science.

These performance issues precipitated by the promise of a jackpot arose from impaired motor preparation, the brain recordings suggested.

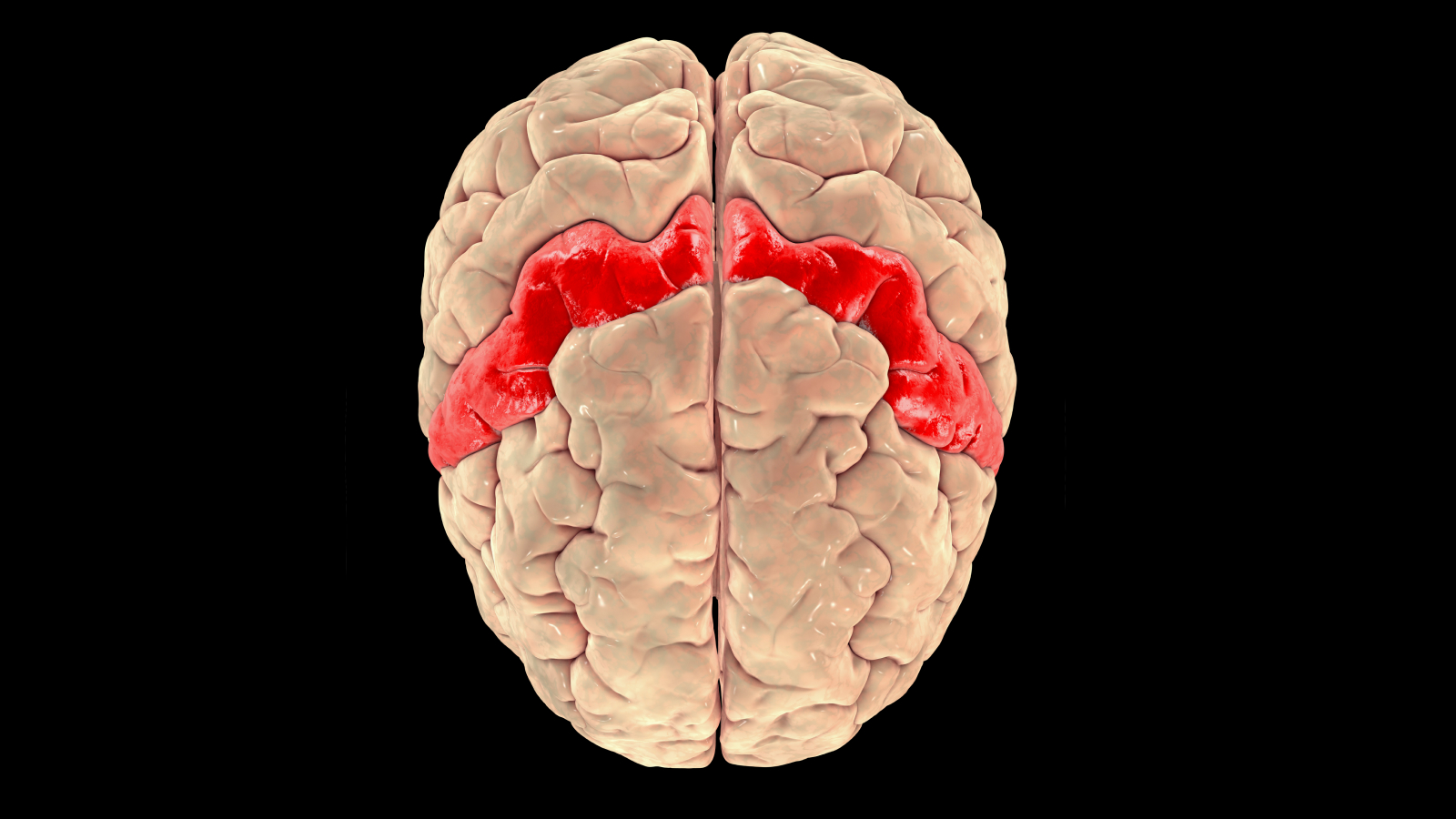

Motor preparation mainly takes place among neurons in the so-called primary motor cortex and the premotor cortex. Previous research suggests that these parts of the brain have an "optimal zone" — a signature of activity that's consistently tied to success in a given task.

According to the authors, the new study shows that the size of a reward determines whether the brain reaches this optimal zone. The presence of a reward pushes the brain toward this optimal place, but when the reward gets too large, it exceeds it, co-senior author Steven Chase, a biomedical engineering professor at Carnegie Mellon University, told Live Science.

Related: The brain can store nearly 10 times more data than previously thought, study confirms

These findings could be relevant to humans because reward processing is central to many aspects of human life, as well as psychiatric conditions. "Addiction is a place where the reward system has gotten it wrong — where it's finding behavior to be rewarding that is actually super harmful to the individual," Chase said. "Obsessive-compulsive disorder is another case."

The researchers now hope to explore whether they could help bring about these "optimal" neural signatures to help someone perform at their best. "One of the things that we would love to understand is how we can sort of make that kind of psychological training a little bit more formal and repeatable," Chase said.

The study's findings coincide with established theories about how arousal — meaning alertness and attention — affects performance, but they add value because they highlight specific neural pathways involved, said Christopher Mesagno, a senior lecturer at Victoria University in Australia who studies anxiety in sports performance and was not involved in the study.

However, Mesagno told Live Science in an email that the human concept of "choking under pressure" can be related to social anxiety, a phenomenon that may not be observed in monkeys. He suggested that future studies could include large groups of humans and experimental conditions that evoke social anxiety.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Christoph Schwaiger is a freelance journalist. His main areas of focus are science, technology and current affairs. His work has appeared in a number of established outlets in various countries. When he's not busy hosting the discussions himself, Schwaiger is also a regular guest on different news programs and shows. He loves being active and is regularly spotted helping out organizations that champion causes that are close to his heart. Schwaiger holds an MA in journalism.