New 3D map charted with Google AI reveals 'mysterious but beautiful' slice of human brain

Harvard and Google researchers have collaborated to map a tiny fragment of an adult human brain in unprecedented detail.

Researchers have mapped a tiny sliver of the human brain on an unprecedented scale, vividly detailing each brain cell, or neuron, and the intricate networks they form with other cells.

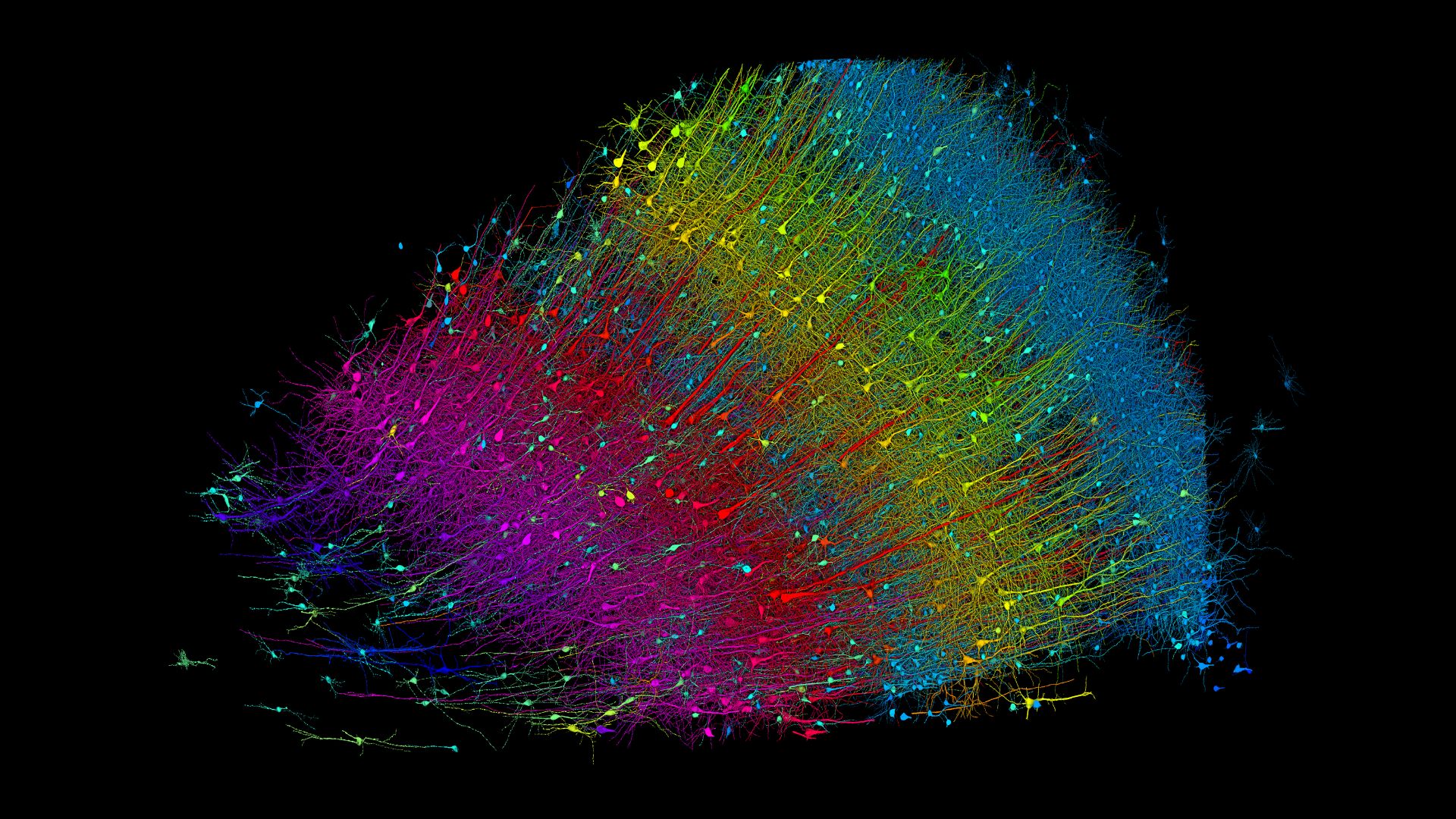

The groundbreaking brain map, which was constructed by Harvard and Google researchers, reveals roughly 57,000 neurons, 9 inches (230 millimeters) of blood vessels and 150 million synapses, or the connection points between neurons.

Dr. Jeff Lichtman, a professor of molecular and cellular biology at Harvard University who co-led the 10-year-long project, said he couldn't believe the detailed map when he first saw it. "I had never seen anything like this before," he told Live Science.

The human brain is a vastly complex organ with about 170 billion cells, including 86 billion neurons. Researchers have previously peeked into the brain at the scale of millimeters using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). And more recently, advanced microscopy techniques have revealed details at a much smaller scale, improving our understanding of the brain's inner workings.

Related: Most detailed human brain map ever contains 3,300 cell types

Now, using these microscopy methods and an artificial intelligence (AI) system called machine learning, Lichtman and his colleagues have created a 3D map from a piece of brain at the scale of a nanometer, or 1-millionth of a millimeter. This presents a picture of the organ at the highest resolution scientists have ever achieved.

The resulting cell atlas, described in the journal Science on May 9, is also available for scientists to peruse online.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This map charts a tiny piece of brain with a volume of about 1 cubic millimeter — smaller than a grain of rice. A whole adult brain is a million times larger.

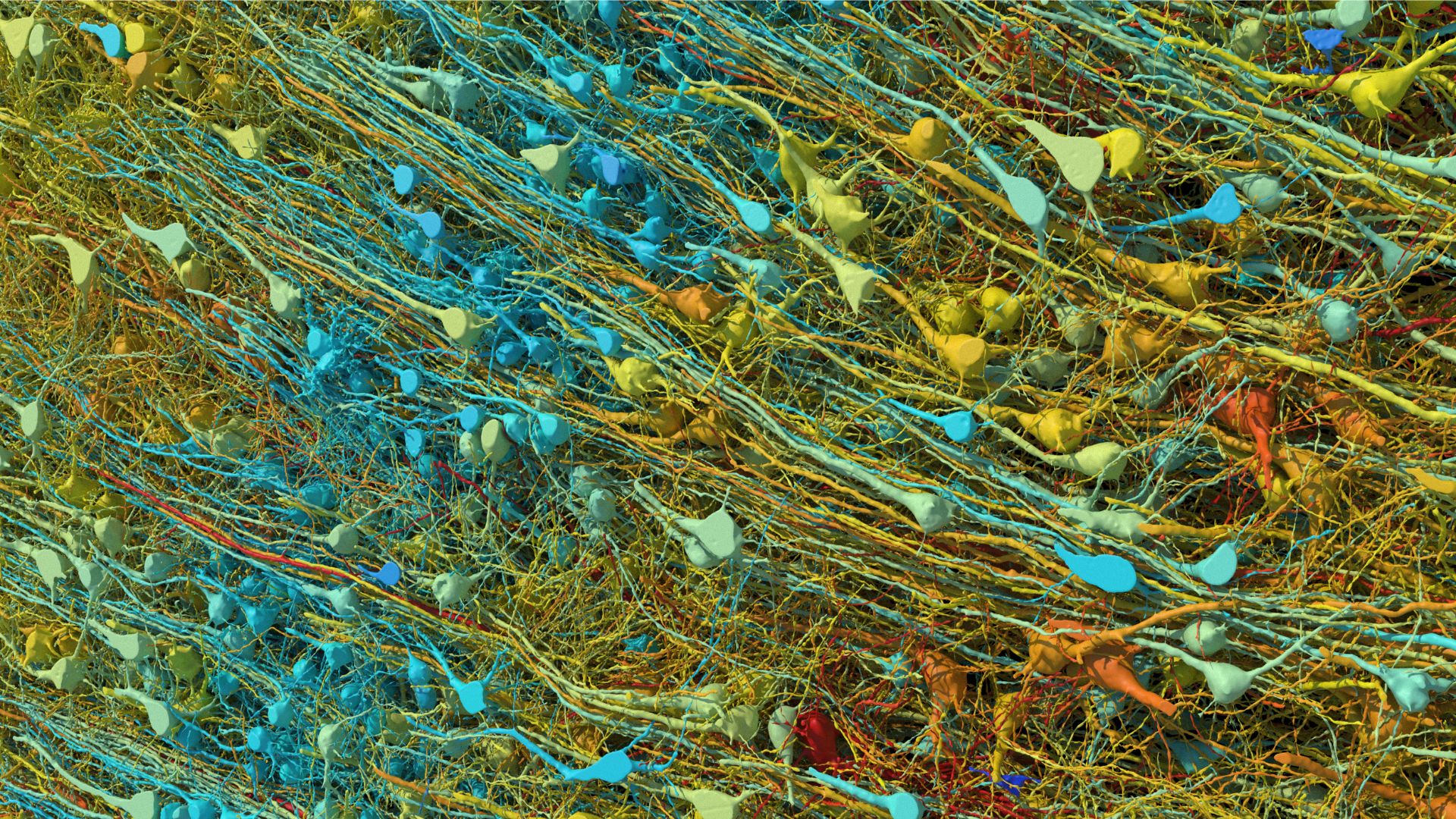

The brain fragment was sampled from a 45-year-old woman who had undergone brain surgery to treat epilepsy. Doctors removed the piece from the cerebral cortex, the outermost portion of her brain. After fixing the sample in preservatives, the researchers stained it with heavy metals to help them see the cells. They then embedded the tissue in resin and cut it into more than 5,000 slices, each measuring about 30 nanometers in thickness.

"That's about a thousandth the thickness of a hair strand," Lichtman said.The team scanned each of the slices with a high-speed electron microscope, which uses multiple beams of electrons to illuminate cells in the sample. They then sent the microscopy data to Google for further analysis using AI.

Google's researchers used machine-learning models to identify the same object in different microscopic images and then create a 3D rendering of every object in all the images. They then electronically stitched the renderings together to reconstruct the whole sample in three dimensions. The final 3D map contains a mammoth 1.4 petabytes, or 1 million gigabytes, of data.

"The amount and complexity of the data generated in this project required Google's ability to develop state of the art machine learning and AI algorithms to reconstruct the 3D connectome," Viren Jain, a senior staff scientist at Google who co-led the project, told Live Science in an email.

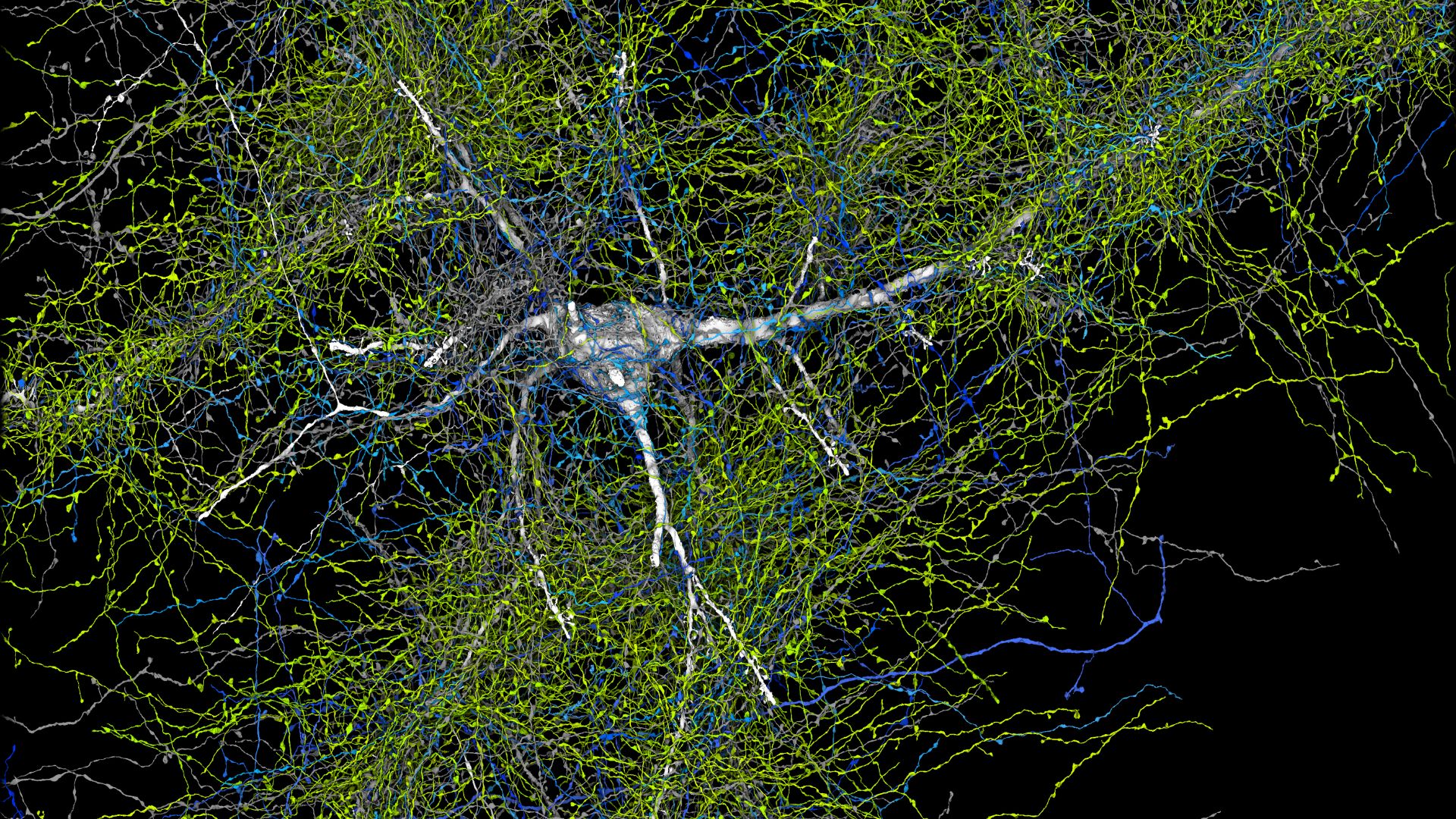

The scientists' detailed map contains several surprises. For instance, they found that some of the neurons' outgoing wires, or axons, wrapped themselves into knots, forming whorls that Jain described as "mysterious but beautiful." The team also found rare connections between neurons, in which singular axons were linked to up to 50 synapses.

"We're still investigating the function of these connections, but they could explain how very fast responses, or very important memories are encoded," Jain told Live Science.

It remains to be seen whether the whorls and super-strong synapses have anything to do with the tissue donor’s epilepsy, or if they'd be seen in brains of people without the condition, Lichtman noted. He added that the team is now examining brain tissue from a person with Parkinson's, so that may start to address the question.

He added it's unlikely that brain tissue samples from any two people will look exactly the same, in part because the way the brain wires itself depends on an individual's experiences.

The team next aims to map the entire brain of a mouse, which would be 500 times the size of this human brain sample. They're starting with the hippocampus, a key region for learning and memory.

"We have already begun the ambitious task," Lichtman said.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Sneha Khedkar is a biologist-turned-freelance-science-journalist from India. She holds a master's degree in biochemistry and a bachelor's degree in microbiology and biochemistry. After her master's, she worked as a research fellow for four years, studying stem cell biology. Her articles have been published in Scientific American, Knowable Magazine, and Undark, as well as several Indian platforms such as The Hindu and The Wire Science, among others. Besides writing, she enjoys a good cup of tea, reading novels and practicing yoga.