Scientists built largest brain 'connectome' to date by having a lab mouse watch 'The Matrix' and 'Star Wars'

Using advanced microscopes that capture brain cell anatomy and activity, a portion of a mouse's brain was mapped and rendered into a 3D atlas that creates new possibilities for neuroscience.

The mammal brain is a complex network of billions of cells connected via trillions of nodes that neuroscientists have yet to tease apart. Now, researchers have mapped the many brain cells and connections in a portion of the mouse brain spanning just 1 cubic millimeter — roughly the size of a grain of sand.

"A millimeter seems small, but within that millimeter there are kilometers of wiring," Jacob Reimer, a neuroscientist at Baylor College of Medicine, told Live Science. Reimer is the senior author of one of 10 new studies in which scientists detailed how they constructed this remarkable brain map.

Reimer is part of the MICrONS consortium, a team of more than 150 researchers from multiple U.S. institutions. In their series of papers published in Nature journals on April 9, the researchers not only unveiled the 3D neural map, called a "connectome," but also described how they used this dataset to explore the brain's workings.

"This approach bridges a fundamental gap in neuroscience between observing what neurons do and understanding how they're connected," Lilianne Mujica-Parodi, a neuroscientist at Stony Brook University who was not involved with the work, told Live Science in an email.

How the brain map was charted

The researchers built the connectome using a live lab mouse that was genetically modified so that its neurons glowed when excited. This enabled researchers to detect the brain cells using a microscope while the mouse watched videos and YouTube clips, including scenes from "Mad Max: Fury Road," "The Matrix" and "Star Wars: Episode VII — The Force Awakens."

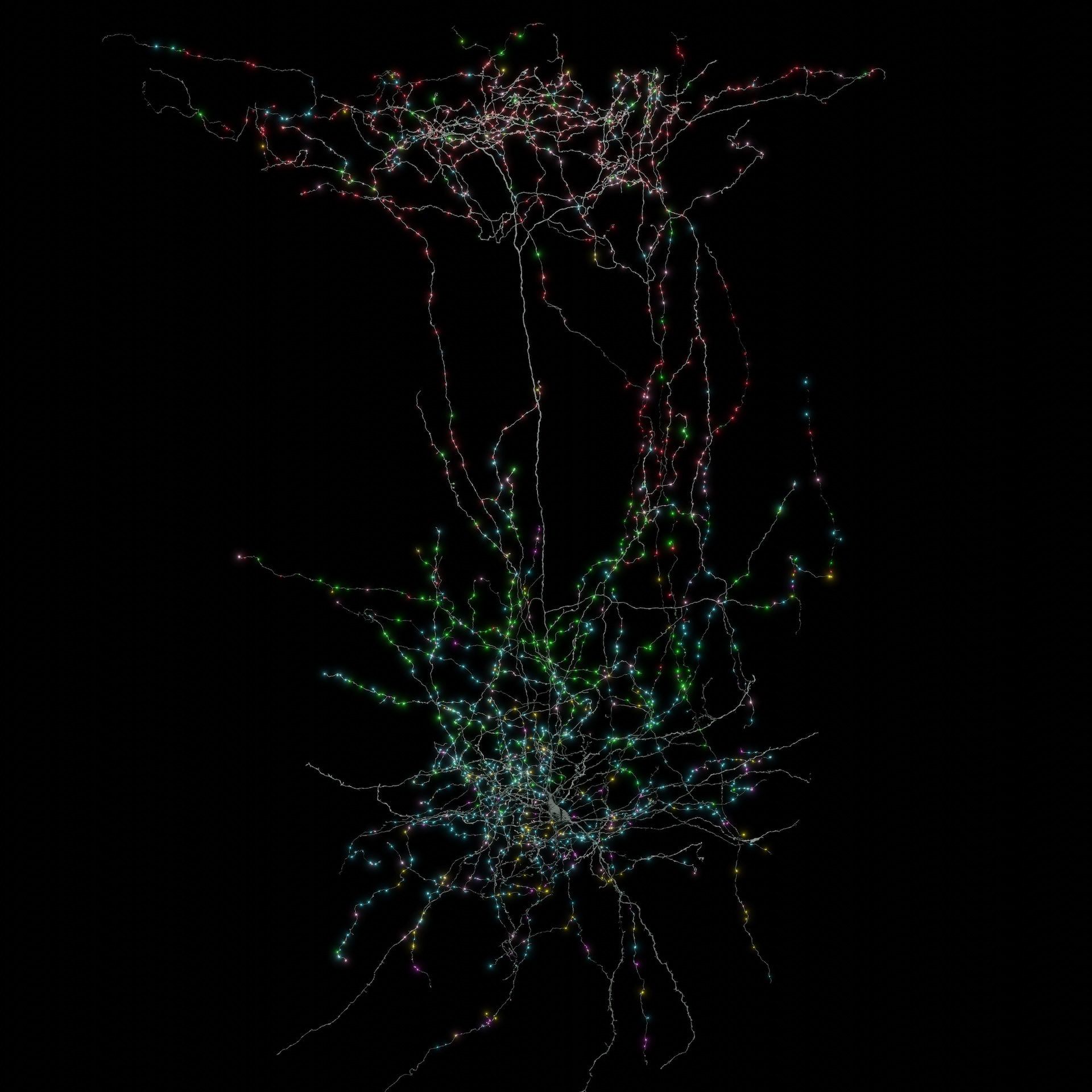

The researchers recorded brain activity from 76,000 neurons in a cubic millimeter block of the occipital lobe, which is located at the back of the brain and is key for visual processing. Later, the team extracted the mouse's brain and examined its anatomical features, such as cell shapes and connections, from the same lobe using an electron microscope.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

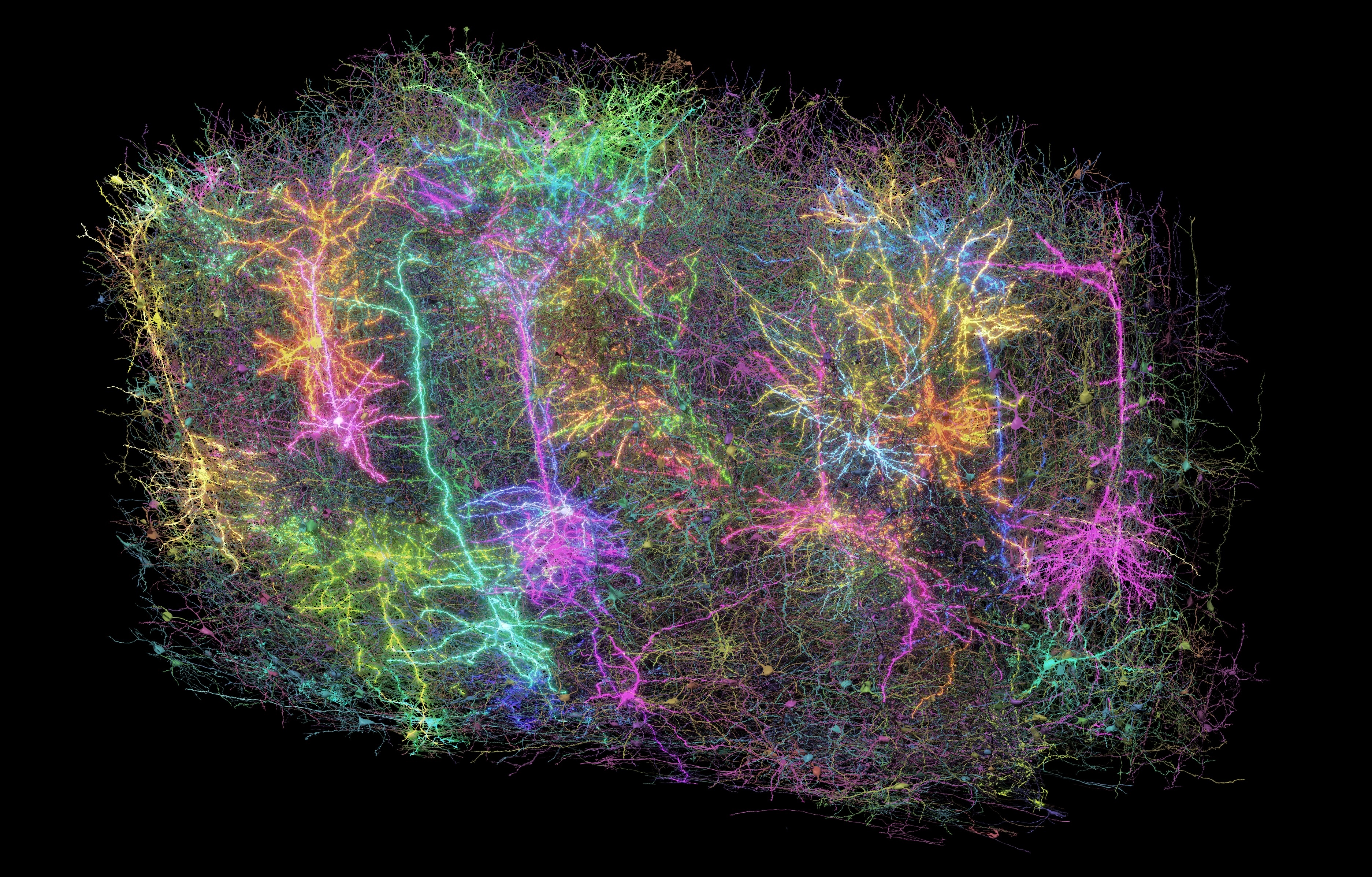

Next, using the anatomical and glowing-cell images as guides, a machine learning algorithm traced the brain cells and their extensions, producing the final 3D map. The cartographic feat contains 200,000 cells and 523 million connections between neurons, called synapses.

The brain contains various types of cells that perform different functions, including neurons, which send signals, and glial cells, which support the function of neurons. The machine learning tool distinguished between tens of cell types based on their physical features.

Forrest Collman, a neuroscientist at the Allen Institute and senior author of two of the papers, said this dataset is three times larger than a connectome taken from part of a human brain and 40 times larger than a connectome of the whole fruit fly brain, making it the largest connectome to date.

Despite how dense the dataset is, Reimer said it's incomplete — some brain cells are missing.

The connectome also contains "orphan" extensions that don't appear to emanate from any cells. This could be because the cells themselves weren't detected by the machine learning algorithm or because the extensions are connected to cells outside the confines of the sampled region.

"There's a lot of proofreading that's required," Reimer said, and much of that double-checking must be done manually by scientists. That said, his team developed a software tool to partially automate this refinement step.

New insights into neural connections

There's an adage saying neurons that "fire together wire together," meaning, at least across short distances, brain cells that activate in tandem are more likely to form connections. The connectome revealed that this pattern also holds true over longer hauls, spanning the 1 mm width of the sampled block.

Collman said the connectome also revealed new information about how so-called inhibitory neurons — which make other neurons less likely to fire — actually switch off firing in excitatory neurons.

Before the connectome was available, neuroscientists weren't sure if inhibitory neurons target specific cells in a given network, rather than just affecting local neurons that happen to be in close reach of their wiring, Collman said. The connectome revealed that inhibitory cells originating from different areas in the brain can converge onto the same target cells located far away, suggesting their inhibition is highly specific.

More insights could come out of this connectome in the future.

"The authors made the data associated with the paper publicly available," said Max Aragon, a neuroscience doctoral student at Princeton University not involved with the work. "This is a massive boon to the neuroscience community," he told Live Science in an email, noting that other researchers can now leverage the data for their own work.

Besides revealing how the brain functions, the connectome could "provide crucial insights for addressing neurological disorders where circuit dysfunction plays a role," Mujica-Parodi said — for example, the buildup of plaques in Alzheimer's disease and the formation of lesions in multiple sclerosis often damage neural networks.

And the work doesn't stop there. "The millimeter cube is immense in one sense," Reimer said, "but it's only a fraction of the mouse's visual system."

In the coming decade, the National Institutes of Health's BRAIN Initiative will focus on developing a connectome of the whole mouse brain, he added, which could help researchers to understand long-distance circuitry between different brain regions.

However, the future of this project is currently uncertain, as Congress has cut $278 million from the funding last year.

Editor's note: Max Aragon previously worked with two of the study authors, Chris Xu and Sven Dorkenwald.

Kamal Nahas is a freelance contributor based in Oxford, U.K. His work has appeared in New Scientist, Science and The Scientist, among other outlets, and he mainly covers research on evolution, health and technology. He holds a PhD in pathology from the University of Cambridge and a master's degree in immunology from the University of Oxford. He currently works as a microscopist at the Diamond Light Source, the U.K.'s synchrotron. When he's not writing, you can find him hunting for fossils on the Jurassic Coast.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.