Secret to lifelong memories sticking is molecular 'glue'

A new study has uncovered the role that a specific molecule in the brain plays in maintaining long-term memory.

Some memories last a lifetime — and now, scientists have revealed a type of molecular "glue" that helps those memories stick around.

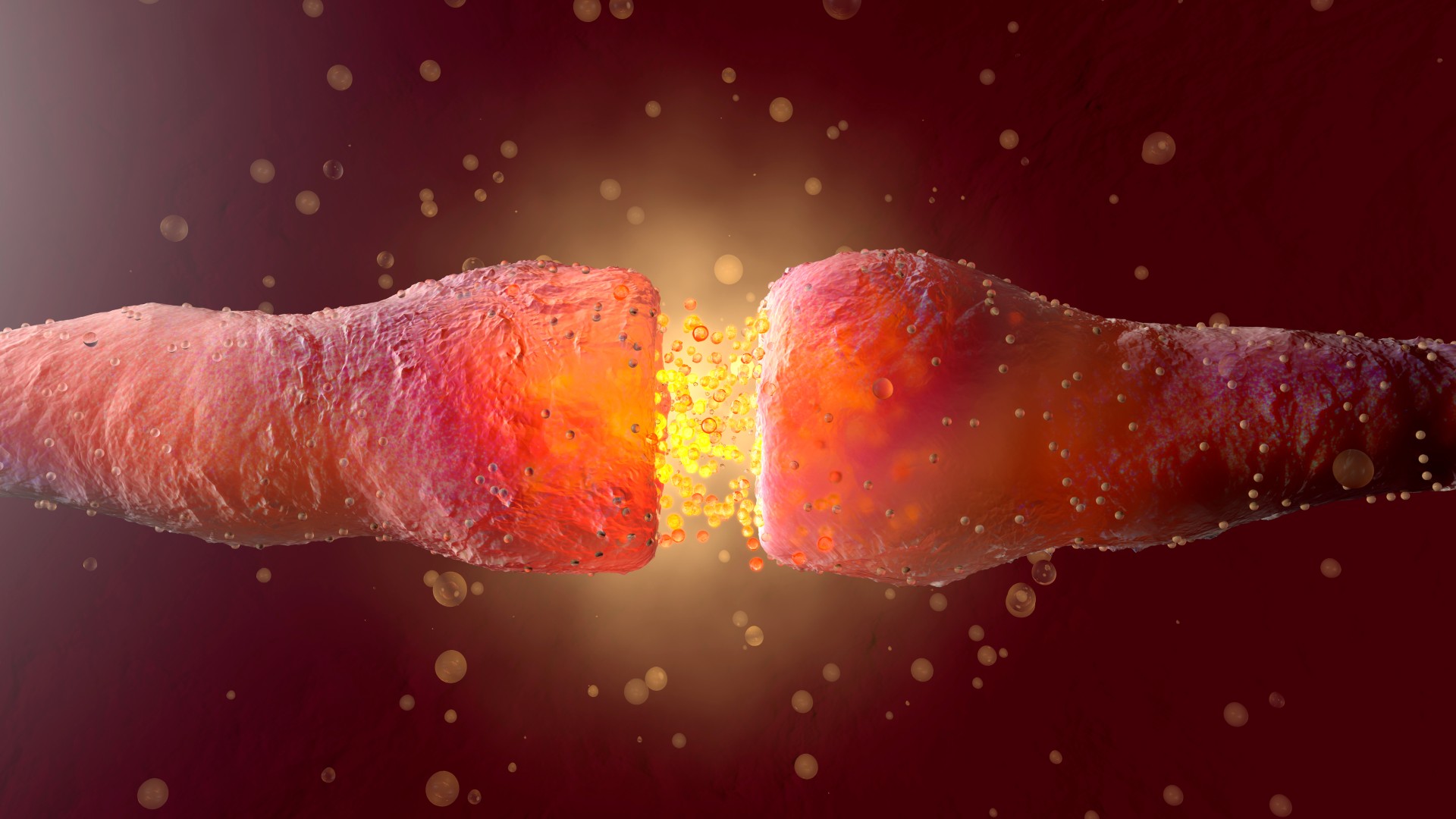

Memories form when collections of neurons in a region of the brain called the hippocampus activate in response to a particular experience. Each time you recall that experience, the same set of cells activates. When one neuron repeatedly activates another, the connection between those neurons strengthens.

Over time, this process in the hippocampus, along with related activity in other regions of the brain, solidifies a short-term memory into a long-term one.

To maintain these long-term memories, brain cells make proteins that help strengthen the connections, or synapses, between neurons. One critical protein is the enzyme PKMzeta, which is continually made by neurons. However, an outstanding question is how this enzyme "knows" to go to the right synapses to ensure that certain memories stay with us forever.

In a new study, scientists think they've found the answer: an unsung molecule called KIBRA glues the enzyme to strong synapses and also summons new PKMzeta to replace that enzyme when it degrades. The researchers published their findings Wednesday (June 26) in the journal Science Advances.

Related: The brain has a 'tell' for when it's recalling a false memory, study suggests

Previous research in humans suggested that different versions of the KIBRA molecule are associated with differences in memory performance, either better or worse. KIBRA was also already known to interact with the PKMzeta enzyme in the hippocampus of mice. So, the scientists behind the new study decided to delve further into that interaction.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In lab experiments, the team investigated whether blocking the interaction between KIBRA and PKMzeta influenced how well mice performed in long-term memory tests. These tests included seeing whether the mice could remember to avoid entering an area where they had previously been shocked with electricity.

Blocking the interaction between KIBRA and PKMzeta impaired the mice's long-term spatial memory — in other words, their ability to avoid the shock zone.

In a separate experiment, when the KIBRA-PKMzeta interaction was left undisturbed, the team found that even when PKMzeta degraded as expected, new complexes of KIBRA and PKMzeta formed in the hippocampus. This, in turn, helped maintain the mice's memory of the shock zone for a month.

Earlier work by the same team showed that if researchers increase the amount of PKMzeta in a rodent's brain, it appears to enhance weak long-term memories that have faded over time. This initially surprised the scientists, as the team expected PKMzeta to boost the strength of synapses at random, rather than specifically acting on those involved in long-term memory.

Instead, the new findings suggest that KIBRA acts like a "glue," sticking to these strong synapses and also guiding PKMzeta to them, which would explain this phenomenon, the team said.

The research is only in its infancy. However, eventually, it may be possible to someday use this knowledge to treat brain disorders that cause memory loss, such as Alzheimer's disease, said study co-senior author André Fenton, a professor of neural science at New York University. Such treatments could work by using KIBRA to deliver PKMzeta or similar molecules to weakened synapses.

However, with neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's, the conditions damage and eventually kill off neurons in the brain. That means that this kind of therapy would theoretically only work for as long as there are still synapses left to enhance.

For now, more research is needed to understand how the interaction between PKMzeta and KIBRA actually translates into people's experiences of memory.

"We have quite a way to go to turn the description of these molecules into that experiential thing that we cherish — what we call memory, belief, intention and so forth," Fenton said.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30. (emily.cooke@futurenet.com)