The brain has a 'tell' for when it's recalling a false memory, study suggests

Specific patterns of electrical activity in the hippocampus may indicate whether someone is about to misremember an event.

Your brain activity changes depending on whether you're recalling a true or a false memory, new research suggests. A "false" memory refers to when you remember something that didn't happen or that actually occured at a different time or place.

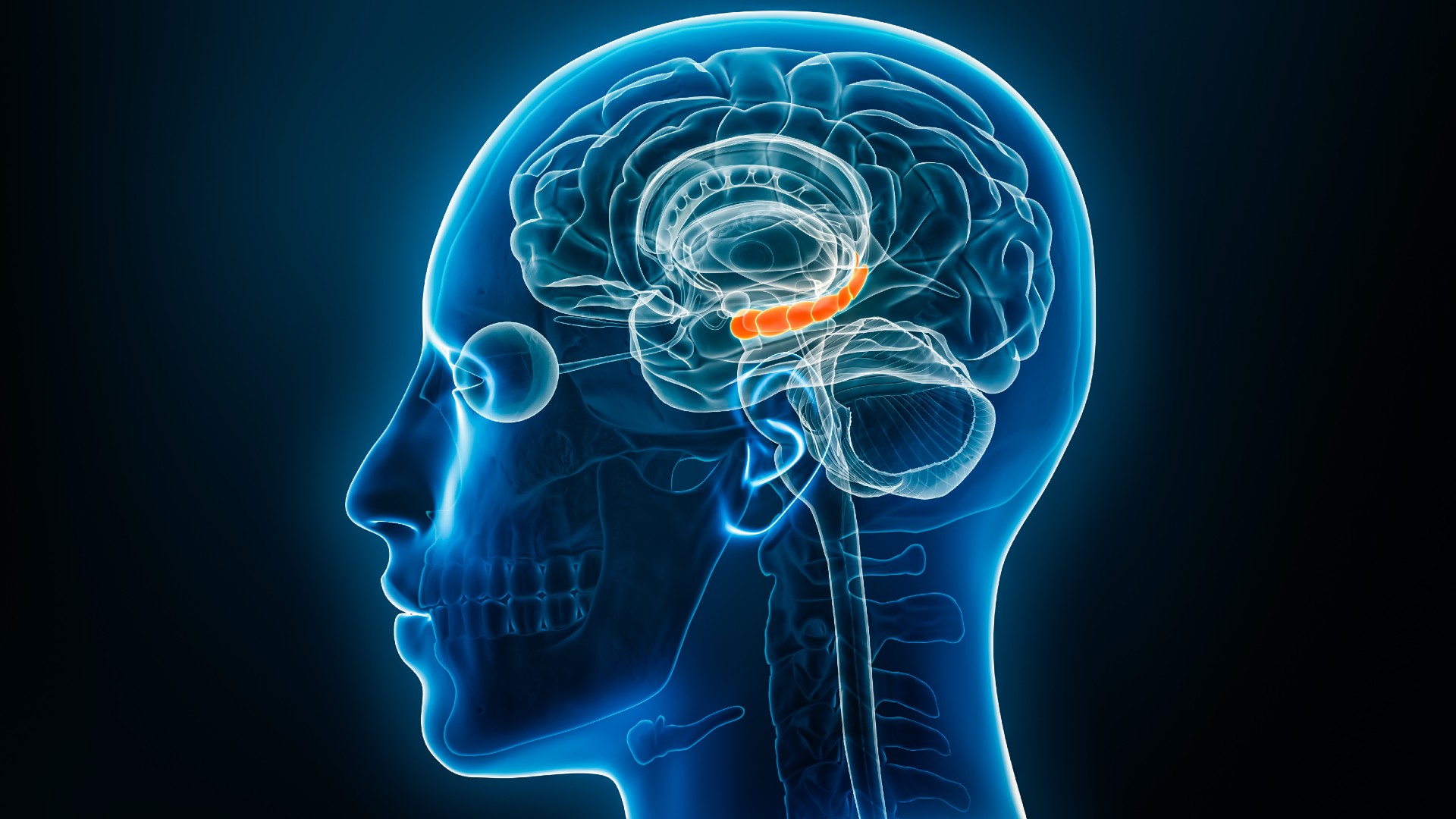

Remembering past events, experiences or information tied to a specific context, such as a birthday party, first date or recent trip to the grocery store, is known as episodic memory; that's opposed to semantic memory, which is related to general knowledge and facts untethered to a time or place and not related to one's own past. Episodic memories are largely controlled by a brain region called the hippocampus, but what happens in the brain structure when people misremember events has been a mystery — until now.

According to the new study, published Sept. 26 in the journal PNAS, a specific pattern of electrical activity erupts in the hippocampus immediately before someone recalls a false memory — and it differs from the electrical activity that occurs when people remember an event correctly.

"Whereas prior studies established the role of the hippocampus in event memory, we did not know that electrical signals generated in this region would distinguish the imminent recall of true from false memories," Michael Kahana, senior study author and a professor of psychology at the University of Pennsylvania, said in a statement.

Related: Neurons aren't the only cells that make memories in the brain, rodent study reveals

A better understanding of this brain activity could help predict when people are going to recall a distressing false memory, far removed from its original context, the study authors suggested.

For example, people with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) "often experience memory intrusions of their traumatic experiences under contexts that are safe and dissimilar to the traumatic incident," they wrote in the paper. In theory, new medical treatments could be designed to monitor and disrupt this brain activity to put a stop to the disturbing flashbacks, the study authors proposed.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the new study, the researchers recorded electrical activity in the hippocampus of patients with epilepsy, who'd already had electrodes implanted in their brains so doctors could track their seizures. The team initially asked the patients to study a list of unrelated words, such as "pizza" and "clock," and then recall them in any order after a brief break. Before studying the "target" word list, the participants had been shown a different list of words that could potentially trip up their memories. In such tests of episodic memory, the words are contextually bound together by their source, meaning the word list on which they're presented.

The rhythm of electrical activity in the hippocampus differed dramatically when patients correctly recalled a word from the target list or incorrectly remembered one that hadn't been included. This electrical activity appeared less than a second before they said the word and then faded quickly afterward.

Interestingly, if a patient incorrectly recalled a word from the other list they'd been shown, their hippocampal rhythms were more similar to those seen when they recalled correct words. The rhythm differed most significantly when they said a word they'd never been shown. The authors hypothesized that this was likely because the patients were in the same situational context — sitting at the same seat in the same room — when they stored the memories of the words on both lists. In other words, the shared context made the memories more similar to one another in the brain.

In a second experiment, the authors asked the patients to study and recall related words, categorized as flowers, fruits and insects. The importance of situational context was also shown in this test. For example, after a patient studied the flower list, if they recalled an incorrect but similar word, such as "sunflower" instead of a "lily," their hippocampal rhythm was more similar than if they'd recalled a word that was completely unrelated, such as "clock."

The authors wrote that these findings may explain how the hippocampus distinguishes between similar memories made in different contexts — for example, what you cooked for dinner tonight versus last night. And it may pave the way for new therapies to treat diseases where memory recollection goes haywire. However, it's still unclear whether these electrical signatures are actually responsible for the false memories or just happen at the same time. Future studies could explore this by experimentally manipulating brain activity, the authors wrote.

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30. (emily.cooke@futurenet.com)