Tinnitus may stem from nerve damage not detectable on hearing tests

People with tinnitus may be wrongly classed as having "normal hearing" because standard tests don't detect the condition's true cause, a new study suggests.

People with tinnitus experience persistent ringing or buzzing in their ears that can significantly impact their quality of life — and now, scientists think they finally know what causes the condition.

A new study revealed that people with tinnitus have damage to specific fibers within their auditory nerve that is not detected by standard hearing tests. In addition, neurons in the brainstem — a region at the bottom of the brain that connects to the spinal cord — are more active in response to noise in people with tinnitus than in those who have never experienced it.

The findings, published Thursday (Nov. 30) in the journal Scientific Reports, support an existing theory that tinnitus is caused by a subtle loss of hearing, which in turn prompts the brain to overcompensate by ramping up the activity of neurons involved in the perception of sound. As a result of them being hyperactive, people hear what seem like "phantom sounds."

Knowing what causes tinnitus could take researchers a step closer to developing a cure, the authors told Live Science.

Related: 1 billion teens and young adults risk hearing loss from listening devices

"We're not talking about a treatment — for the first time, we're talking about a possible cure," said Dr. Stéphane F. Maison, clinical director of the Tinnitus Clinic at the Mass Eye and Ear hospital in Boston.

Approximately 1 in 10 adults in the U.S. have experienced tinnitus, which can be triggered by many things, including exposure to loud music at a concert or an ear infection. Tinnitus can last just minutes or become chronic and last for years.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the new study, the authors recruited 201 people who said they'd never had tinnitus in their lives, 64 who had experienced it "at some point" and 29 who had chronic tinnitus, meaning their symptoms had continued for at least six months. The researchers tested the participants' hearing using a gold-standard clinical tool called an audiogram.

"In the clinic, we ask patients to raise their hand whenever they hear a tone and what the audiologist does is measure the threshold, or the lowest level at which you can detect those tones, to try to figure out your hearing sensitivity," Maison said.

All the participants passed this test, so they technically qualified as having "normal hearing."

However, when the authors placed electrodes in the participants' ears and measured the electrical activity of the auditory nerve and brainstem in response to clicking sounds, they discovered that people with tinnitus had damage to a specific type of fiber that responds to louder sounds.

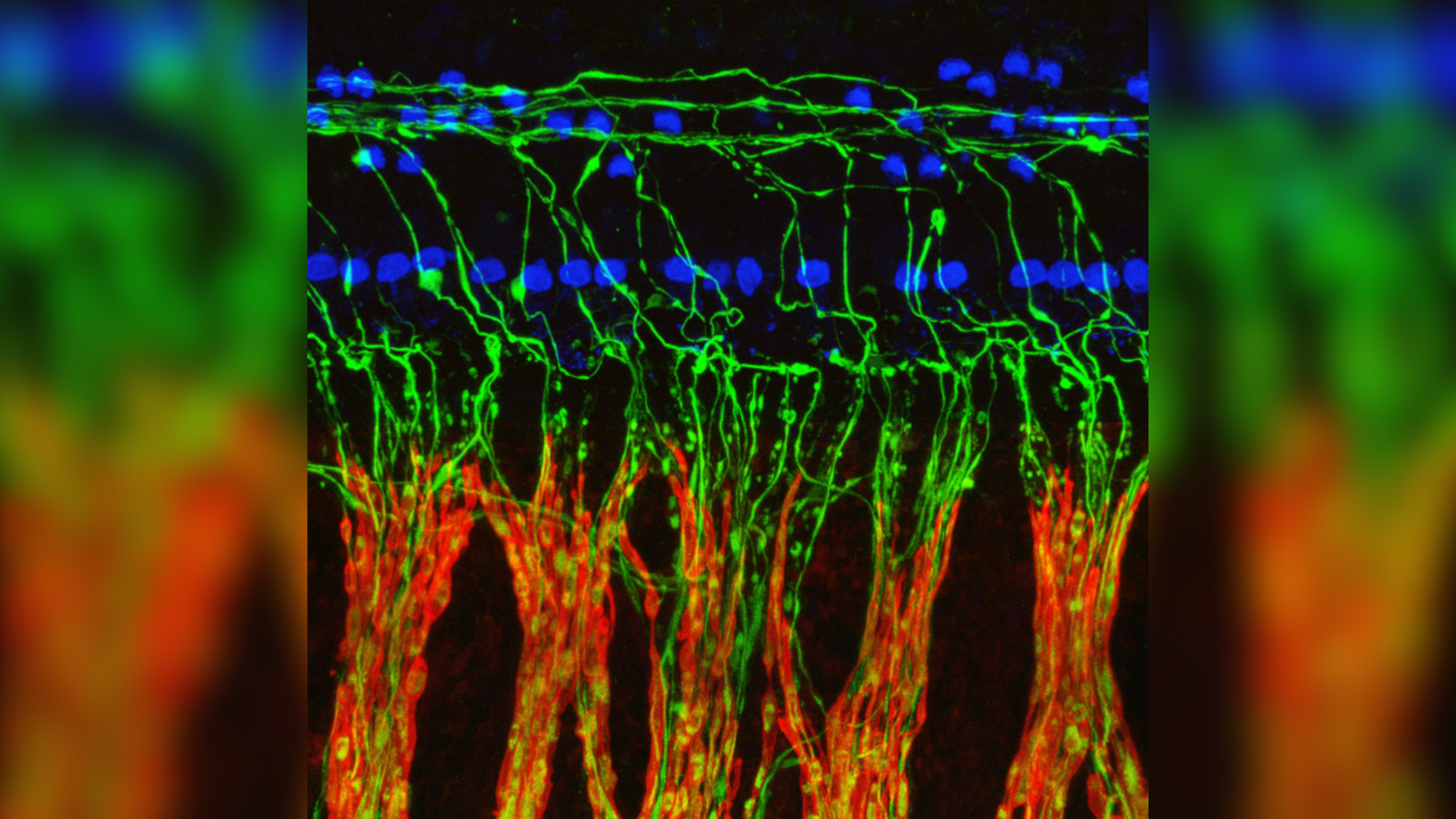

Within the inner ear is a snail-shaped chamber called the cochlea, which contains cells that detect vibrations and convert them into electrical signals. These signals are then carried by auditory nerve fibers via the brainstem to the auditory cortex in the brain, which interprets the signals as sounds.

When someone tunes into quiet sounds, such as during a private conversation, they only need to rely on one set of auditory nerve fibers that respond to quiet noises, Maison said. However, if they're chatting in a noisy environment, they also need input from fibers that respond to louder sounds, he said.

These latter fibers are more likely to become damaged as people age or as a result of excessive noise exposure. However, this specific damage may not be detected by regular hearing tests that only assess a person's ability to hear quiet sounds, he said.

This may explain "hidden hearing loss" where people are assessed to have normal hearing despite struggling to hear in noisy environments.

In the study, people with tinnitus also had greater activity in the neurons of their brainstem in response to the clicking sounds. Maison believes this reflects how the brain is compensating for a loss in auditory nerve function.

The new study hints that tinnitus could be treated with repairs to the damaged auditory nerve fibers. For example, it may be possible to treat tinnitus by regenerating the auditory nerve using growth factors called neurotrophins, Maison said. That would mean the brain would no longer have to compensate for hearing loss, so the person's tinnitus may subside.

However, this research is still in its early days, so it's unlikely such a treatment will be available soon.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30.