Common weight-loss surgery for teens may weaken their bones

Sleeve gastrectomies can help teens and young adults lose weight, but the surgery could also poorly affect their bone health.

A common weight-loss surgery for teens and young adults with obesity is weakening patients' bones, a new study finds.

Sleeve gastrectomies permanently remove roughly 75% of a patient's stomach to curb their appetite and promote weight loss; this is the most common type of weight-loss surgery performed in teens and adults, worldwide. Weight-loss surgeries like this have also become increasingly common for teens in the U.S. in the past five years.

While evidence suggests these surgeries can help reduce the cardiometabolic risks associated with obesity, such as high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes, they can also reduce bone strength, according to the new study, published Tuesday (June 13) in the journal Radiology.

"We should not forget the bone," said study co-author Dr. Miriam Bredella, a radiologist and professor of radiology at Harvard Medical School. "It's really important that [physicians] are aware of bone health after weight-loss surgery," she told Live Science.

The study followed 54 participants between the ages of 13 and 24 with moderate to severe obesity, as measured by their body mass index (BMI), a rough estimation of body fat made using a person's weight and height. The participants were split into two groups: 25 participants underwent a sleeve gastrectomy and 29 received only dietary and exercise counseling.

Related: How body fat is calculated

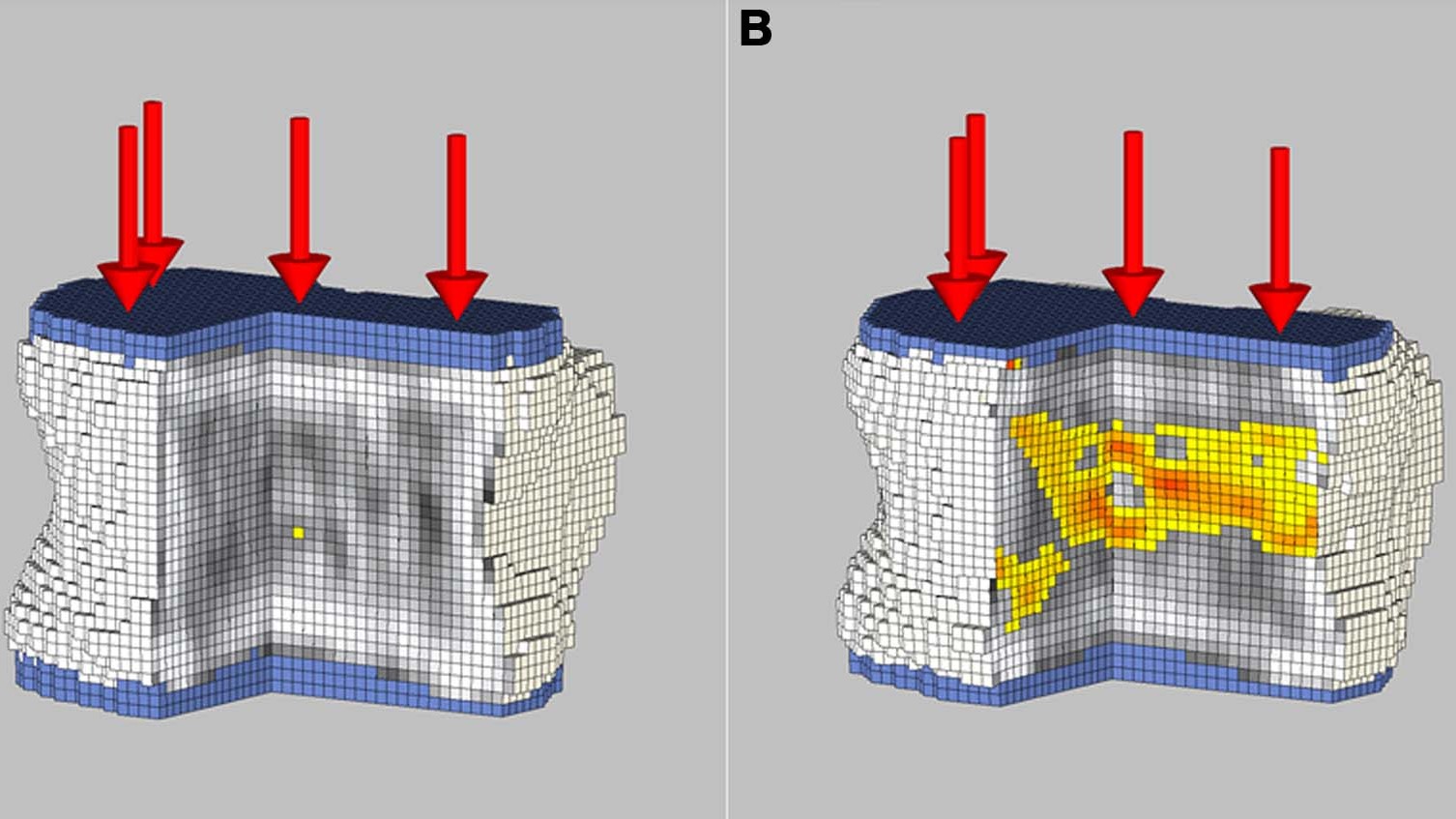

Before each participant's treatment and then two years later, the scientists tested the patient's bone health through physical exams, blood tests and scans, including quantitative CT scans of their spine, used to measure changes in bone mineral density. The researchers then modeled how these changes would affect bones' strength using finite element analysis, a "method that's typically used when you design airplanes or bridges or cars to test the strength of material," said Bredella. This model can help researchers predict what force is required for a bone to break.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"This is novel information in young people, which is important," said Dr. Thomas Link, a radiologist and professor at the University of California, San Francisco, who was not involved in the study. "It also includes information on bone strength and bone marrow fat which are newer technologies characterizing the bone quality," he wrote Live Science in an email.

The sleeve gastrectomy patients had significantly lower BMIs two years out, while the counseled patients' BMIs slightly increased, on average. However, the surgery group had lost bone density in their lower spine and had significantly more fat in their bone marrow, which can weaken overall skeletal strength.

Previous studies have suggested that adults also lose bone density after sleeve gastrectomies, the study authors wrote, but bone loss in adolescence is of particular concern. "Adolescence is the time where you really have the most bone accrual," Bredella said. "It's really the critical time because once we are 20 or 25, we have our peak bone mass and from then on, it goes downhill, so these pubertal years are so critical."

So why would getting surgery on your stomach affect your bones? Decreasing the size of the stomach can also limit the nutrients your body absorbs from food, including vitamin D and calcium, which are critical for bone growth. Sleeve gastrectomies could also affect hormones normally released by the stomach that help support bone strength, Bredella said. And again, having less weight to carry can affect bone strength. But people can help counter this through weight-bearing exercises.

Weakening bones in adolescence could increase the risk of fractures later in life. However, obesity also carries various long-term health risks, and recently released guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics urge doctors to treat adolescent obesity early and aggressively.

While promoting bone health is crucial, "heart trumps the bone," said Bredella. Rather than avoiding weight-loss surgeries altogether, she recommends that individuals adopt a healthy diet before being treated to help reinforce their bone strength, and take vitamin D and calcium supplements after their surgery, and likely for the rest of their lives.

"I hope that for our paper, we raised the awareness of bone loss because people just don't think about it," said Bredella.

Kiley Price is a former Live Science staff writer based in New York City. Her work has appeared in National Geographic, Slate, Mongabay and more. She holds a bachelor's degree from Wake Forest University, where she studied biology and journalism, and has a master's degree from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program.