Scientists invent nanorobots that can repair brain aneurysms

Tiny robots much smaller than blood cells could deliver clot-forming drugs where they're needed most, a study in rabbits suggests. The tech has yet to be tested in humans.

Robots smaller than most bacteria could deliver drugs right to the site of a brain aneurysm, preventing a devastating stroke, a new animal study suggests.

The new technology has been tested only in rabbits so far. But with further study, it could become an alternative to the stents and coils that are currently used to stabilize aneurysms in human patients.

These implants can stop the bleeding caused by an aneurysm, in which the wall of an artery weakens and balloons out. But the treatments can also have problems, such as the risk of bleeding starting up again or of the procedure only partially repairing the aneurysm. There can also be a need to take blood thinners indefinitely to avoid clots, said Qi Zhou, a research associate in bioinspired engineering at the University of Edinburgh and the co-author of a new paper describing the nanorobots.

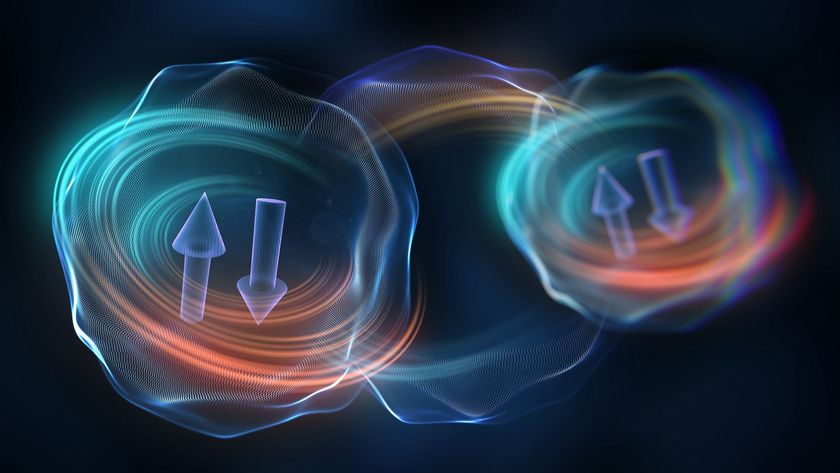

"Our remotely controlled magnetic nanorobots provide a more precise and safer way to quickly seal off cerebral aneurysms without using implants," Zhou told Live Science. "They can also mitigate the painstaking task for surgeons to thread a long and thin microcatheter through complex networks of blood vessels."

Related: Self-healing 'living skin' can make robots more humanlike

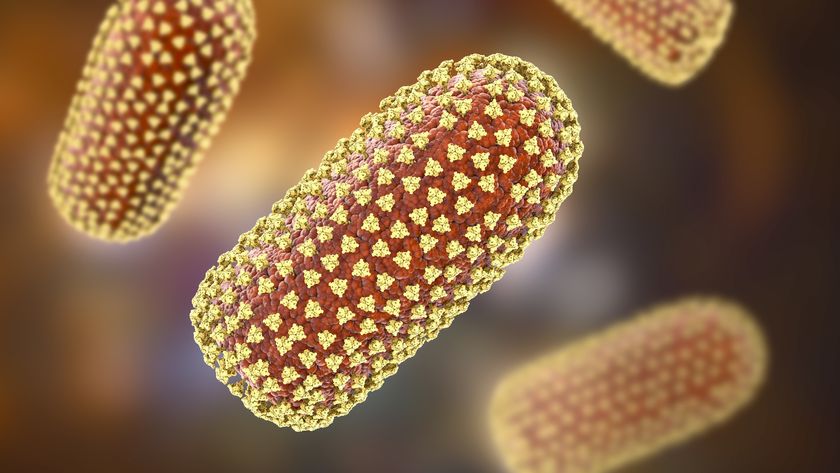

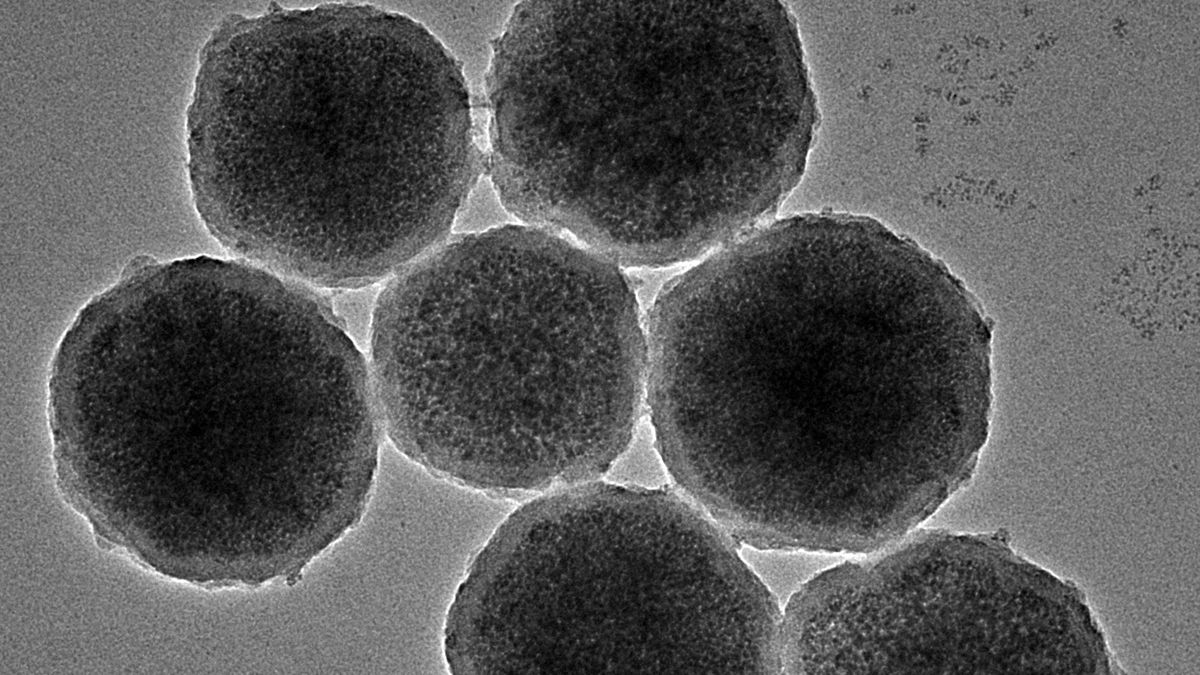

Aneurysms can form in any artery in the body. When they form in the brain, they can burst and cause a stroke. To devise a new solution for these dangerous events, Zhou and his colleagues developed nanobots that measure just 295 nanometers in diameter. For comparison, a typical virus is about 100 nanometers wide, and most bacteria measure in the 1,000-nanometer range.

Each bot consists of a magnetic core, a clotting agent called thrombin that treats the aneurysm, and a coating that melts when lightly heated, in order to release the medication.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Using a magnetic field, the nanorobots can be guided to the aneurysm," Zhou said. "Then focused heat is used to melt the coating, release the drug and block the aneurysm from the blood circulation." This heat is delivered with an alternating magnetic field, which essentially creates friction by messing with the alignment of particles exposed to the field. The temperature is kept under 122 degrees Fahrenheit (50 degrees Celsius) so it does not damage body tissue.

The idea is that cardiovascular surgeons could release these nanorobots in the bloodstream, upstream of the aneurysm, using a microcatheter. This would prevent doctors from having to intrude too deeply into the fine vessels of the brain.

In the new study, published Thursday (Sept. 5) in the journal Small, the researchers first tested the biocompatibility of the nanorobots in human cells in lab dishes. A biocompatible material can be introduced into living tissues without causing harm or unwanted side effects. They also did preliminary animal studies, treating three rabbits for aneurysms artificially induced in the carotid arteries, which feed the brain and the head.

"We found that the nanorobots could be successfully guided to the aneurysm in a clinical interventional setting and quickly form a stable clot to block it off completely," Zhou said.

During a two-week follow-up period, the three rabbits remained healthy, with stable clots blocking their aneurysms. These clots don't block the brain's blood supply but rather close off the weak spot in the vessel so that it doesn't burst.

Looking forward, the technology will need to be tested in larger animals that better mimic the human body, Zhou said. The researchers will also need to test the safety and efficacy of the nanorobots in longer-term studies, to see how animals fare in the long run, he added. In the rabbit tests, the aneurysms were at a shallow depth, so the team will also need to improve the magnetic control system to better guide the bots to aneurysms deep inside the brain.

"There is more work to be done, but we believe this technology has the potential to revolutionize the way we treat brain aneurysms," he said.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.