New stem cell therapy could repair 'irreversible' and blinding eye damage, trial finds

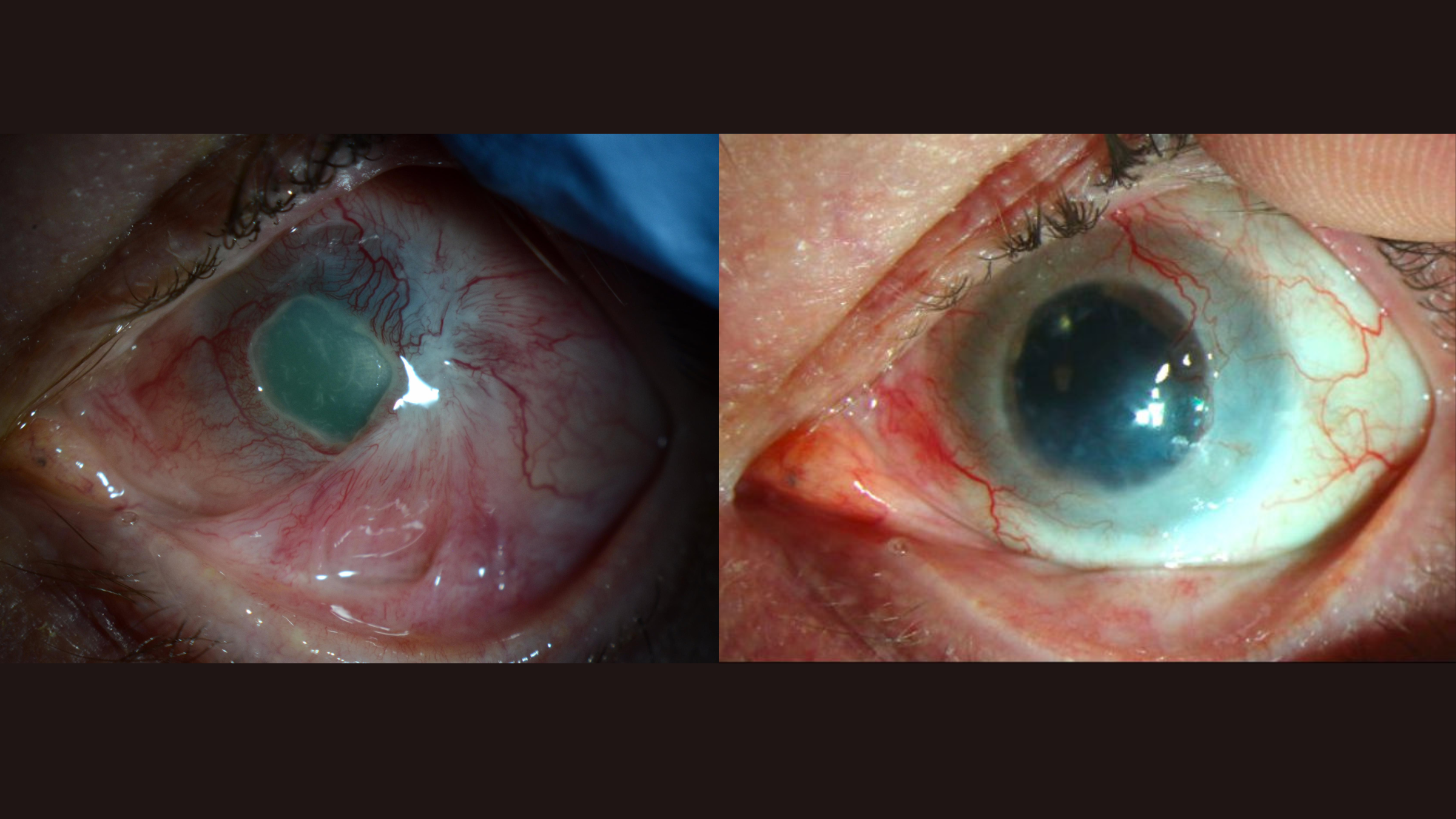

A new therapy repairs corneal damage to a patient's eye using stem cells from their other, healthy eye.

A new stem cell therapy has repaired blinding damage to the cornea in 93% of patients in an early clinical trial.

The cornea is the clear dome that covers the front of the eye and helps to focus light to enable you to see clearly. On the outer edge of the cornea are stem cells, called limbal epithelial cells, that have the potential to become any other type of corneal epithelial cell. As such, these stem cells can replace any corneal cells that are damaged through injury or normal wear and tear over time.

However, severe injuries, such as those caused by chemical burns or infections, can completely destroy these stem cells, as can Stevens-Johnson syndrome, a condition that can cause blistering of the mucous membranes of the eyes. In these instances, the cornea is permanently damaged, resulting in blindness in the affected eye. Patients with this type of eye damage can't be treated with regular corneal transplants because these use donated tissue to replace only the very center of the damaged cornea. That's opposed to the missing stem cells from the outer edges which are vital for repair purposes.

One potential solution is to restore the lost stocks of stem cells in the patient's damaged eye using healthy cells from their other, healthy eye. In this procedure — known as "cultivated autologous limbal epithelial cell transplantation" — doctors take stem cells from the healthy eye, grow them into sheets of cells in the lab, and then surgically transplant them into the damaged eye.

Related: Gene-therapy drops restore teen's vision after genetic disease left his eyes clouded with scars

The treatment was initially tested in 2018 in a small clinical trial at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear hospital in Boston. The trial involved four patients, each of whom had chemical burns to one eye. This was the first-ever stem cell therapy for the eyes to be performed in the U.S., the team said at the time. The patients were tracked for a year after transplantation, during which time the procedure was shown to be feasible, safe and potentially effective.

Now, the same research team has released the results of a larger trial of 15 patients who were tracked for 18 months following treatment. According to a paper published Tuesday (March 4) in the journal Nature Communications, the patients had blinding cornea injuries from various causes, such as chemical burns, thermal burns or viral infections of the eye.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The treatment was successful in 14 of the 15 patients after 18 months.

Treatment "success" in the trial was defined in three ways, trial runner Dr. Ula Jurkunas, associate director of the Cornea Service at Massachusetts Eye and Ear, told Live Science. Namely, it meant that the surface of the damaged cornea was restored, that blood vessels that once obscured vision in the affected eye had receded, and that the patients experienced less eye pain and discomfort. There were also no serious side effects of transplantation itself. However, one patient developed a bacterial infection unrelated to the treatment.

The team didn't directly measure changes in vision as a marker of success because simply restoring the surface of the cornea with stem cells does not mean that vision will immediately improve, Jurkunas said. If the other layers of the cornea remain damaged, a patient may still need a regular corneal transplant to get their vision back, she clarified.

However, notably, around 70% of the patients showed improved vision at the 18-month mark, she said.

On average, the patients with the most severe corneal damage took longer to respond to the treatment than those with less-severe damage, Jurkunas said. This probably explains why one patient, who had an extensive eye injury, didn't fully benefit from the treatment after 18 months, she theorized.

The new therapy can only treat patients who are blind in one eye, as it relies on using stem cells from their remaining healthy eye. However, in the future, the team would like to develop the treatment so they can use stem cells from organ donors, rather than using patients' own tissues. That way, they'd be able to treat both eyes in patients who need it, but the risk of immune rejection would still need to be considered.

The team will now test whether the therapy works in more people and for longer than 18 months. They also plan to directly compare the therapy to a sham treatment as part of a randomized controlled trial, the gold standard of clinical trials. This will allow them to more reliably determine whether the therapy actually works.

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30. (emily.cooke@futurenet.com)

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.