'She was waiting for a 1-in-a-million match': Alabama woman is the 3rd patient to ever get a pig kidney

An Alabama woman underwent a transplant procedure to get a new kidney from a gene-edited pig.

Last month, a woman became the third living person to receive a pig kidney. Now, her kidney function is completely normal, and she's off dialysis.

The transplant recipient — Towana Looney, 53, of Alabama — had donated a kidney to her mother back in 1999. A few years later, though, she developed high blood pressure associated with preeclampsia during pregnancy. The condition led her to develop chronic kidney disease, and she needed to start dialysis in 2016. Dialysis does the work of the kidneys by removing waste and extra fluid from the blood.

In 2017, Looney was added to the transplant list, and as a previous kidney donor, she was given higher priority than the average person would be. However, finding a kidney that "matched" Looney's immune system proved extremely challenging.

"Through exposure to other people's tissue, through pregnancies and blood transfusions, she has become sensitized to nearly every tissue type in the population, making it nearly impossible to find a kidney match," Dr. Robert Montgomery, director of the NYU Langone Transplant Institute and leader of Looney's procedure, said at a news conference Tuesday (Dec. 17). "She was waiting for a 1-in-a-million match."

Related: Creating 'universal' transplant organs: New study moves us one step closer.

But Looney had another option: an experimental procedure to get a new kidney from a gene-edited pig.

Now, three weeks out from receiving the kidney, Looney said she's full of energy and feeling grateful.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Emotionally, I'm overjoyed," Looney said at the news conference. "I don't know what I want to do next, what I want to eat next, where I want to go." She later added, "I want to go to Disney World."

Once the kidney was hooked up to the bloodstream, "it functioned essentially exactly like a kidney from a living donor," said Dr. Jayme Locke, a transplant surgeon at the University of Alabama at Birmingham who studies animal-to-human transplantation and initiated Looney's application for a pig kidney.

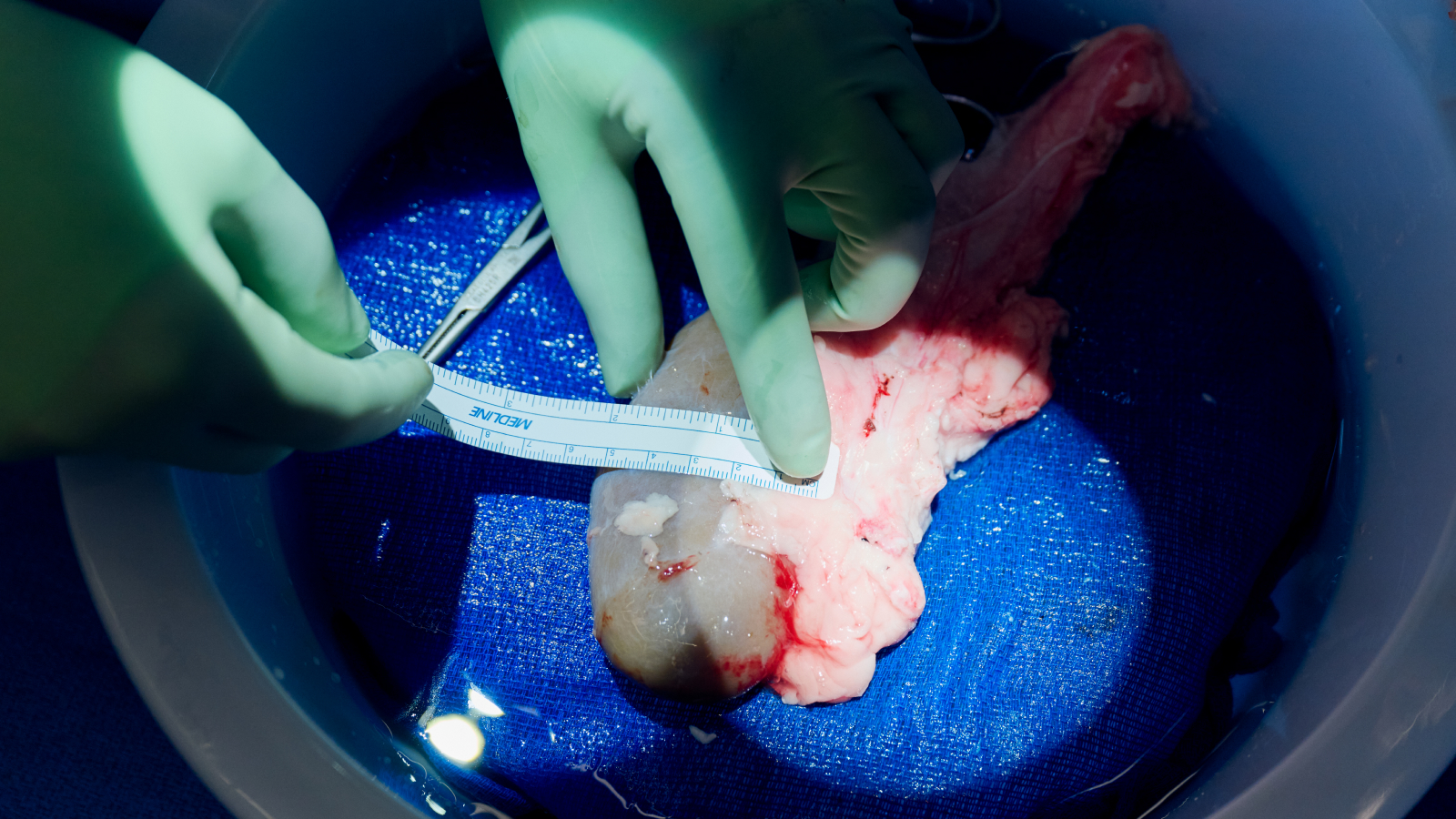

Looney's new kidney came from Revivicor Inc., a subsidiary of United Therapeutics. The company tweaked the donor pig's genetics to remove pig genes and add human ones. Looney is the first living patient to receive a kidney with 10 gene edits; the two previous recipients received kidneys with just one gene removed. The 10-edit kidney has been tested in brain-dead organ donors before, so scientists have a sense of how the human body reacts to it.

Genes for three pig proteins that could set off the human immune system were removed, along with a gene for a pig growth hormone receptor. Six human genes were added, in hopes of making the kidney more compatible with the human body.

While Looney carried a high concentration of antibodies that would have attacked a human kidney, tests suggested that her levels of antibodies that might have attacked the pig organ were "pretty modest," Montgomery said.

Transplant rejection, in which the patient's immune system attacks the transplanted organ, is generally more likely in pig-to-human transplants than in human-to-human ones, Montgomery said. But the emergence of rejection doesn't necessarily mean a patient loses the organ — it means doctors might have to quickly apply strong, immune-suppressing drugs to get the reaction under control, he noted.

Looney will stay near NYU Langone's facility for the next three months so she can be monitored daily for signs of rejection, kidney function issues, and any signs of infection from the pig organ.

A pig virus may have contributed to the death of the person who got the first-ever pig heart transplant, so the transplant team will watch closely for such germs. Looney's kidney was negative for known pig viruses that can sicken humans, Locke noted, but her blood will be monitored for signs of infection nonetheless. Looney is also wearing various health trackers to monitor her physical activity, heart rate and blood pressure.

The NYU team plans to launch a formal clinical trial of the 10-edit pig kidney next year, Locke said. And eventually, they will also run a trial of the single-edit kidney, in part to see which option will suit different patients best.

"I want to give courage to those out there on dialysis — I know it's not easy," Looney said. "And it's not the only option. There's hope."

Disclaimer

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.