Tardigrade proteins could slow aging in humans, small cell study finds

In lab-dishes studies, proteins drawn from tiny tardigrades slowed human cell metabolism.

Proteins found in tiny, indestructible tardigrades could potentially be a key ingredient in slowing the aging process in humans, scientists claim. However, it will take more work to show these proteins are a veritable fountain of youth — for now, the researchers have only early hints from lab-dish experiments..

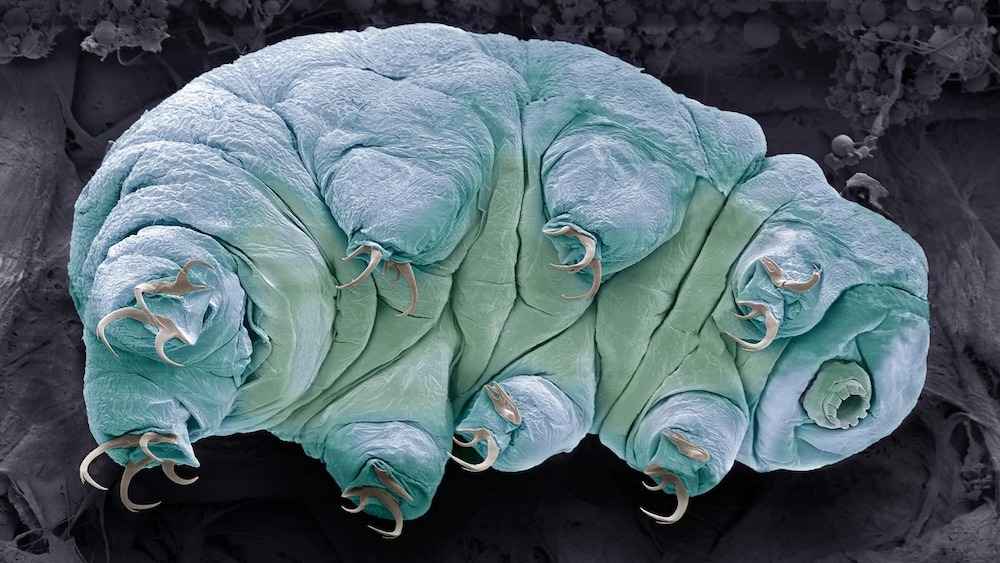

Also known as water bears, tardigrades are near-microscopic, eight-legged creatures known for their practically superhero-like ability to withstand extreme conditions, including tolerating a severe lack of water, surviving in outer space and emerging unscathed from being fired from a gun. To survive such conditions, tardigrades transform into dehydrated balls and dial their metabolisms to near-zero.

Now, scientists have discovered that proteins found in these tiny critters can also slow metabolism in human cells in lab dishes, according to a study published March 19 in the journal Protein Science.

For the study, researchers focused on a tardigrade protein called CAHS D, which transforms into a gel-like consistency when introduced to human cells.

"Amazingly, when we introduce these proteins into human cells, they gel and slow down metabolism, just like in tardigrades," lead study author Silvia Sanchez-Martinez, a senior research scientist in the Department of Molecular Biology at the University of Wyoming, said in a statement. "Just like tardigrades, when you put human cells that have these proteins into biostasis, they become more resistant to stresses, conferring some of the tardigrades' abilities to the human cells."

Related: We finally know how tardigrades mate

Biostasis is a state of suspended animation in which organisms can tolerate unfavorable environmental changes, such as surviving for long periods without water. The scientists have now demonstrated that the proteins that make biostasis possible in tardigrades can have a similar effect on human cells.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Scientists think this new finding could eventually be harnessed to make lifesaving treatments available to people in locations where refrigeration is unavailable and to improve the storage of cell-based therapies.

"Our findings provide an avenue for pursuing technologies centered on the induction of biostasis in cells and even whole organisms [such as humans] to slow aging and enhance storage and stability," the researchers wrote in the new study. The research may even shed light on slowing down the aging process.

Amazingly, the researchers also found that the entire process is reversible, meaning the cells' metabolism can reset back to normal after slowing.

"When the stress is relieved, the tardigrade gels dissolve, and the human cells return to their normal metabolism," senior study author Thomas Boothby, an assistant professor in the Department of Molecular Biology at the University of Wyoming, said in the statement.

Boothby and his team have been studying tardigrades extensively in their lab. Last year, they found that tardigrade proteins can be used to stabilize a drug used to treat hemophilia, a bleeding disorder.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.