10 'superbug' stories from 2024, from bacterial 'Kryptonite' to deep-sea antibiotics

Antibiotic and antifungal drug resistance pose a major public health threat. Live Science is covering the spread of this problem and the potential solutions that are emerging in turn.

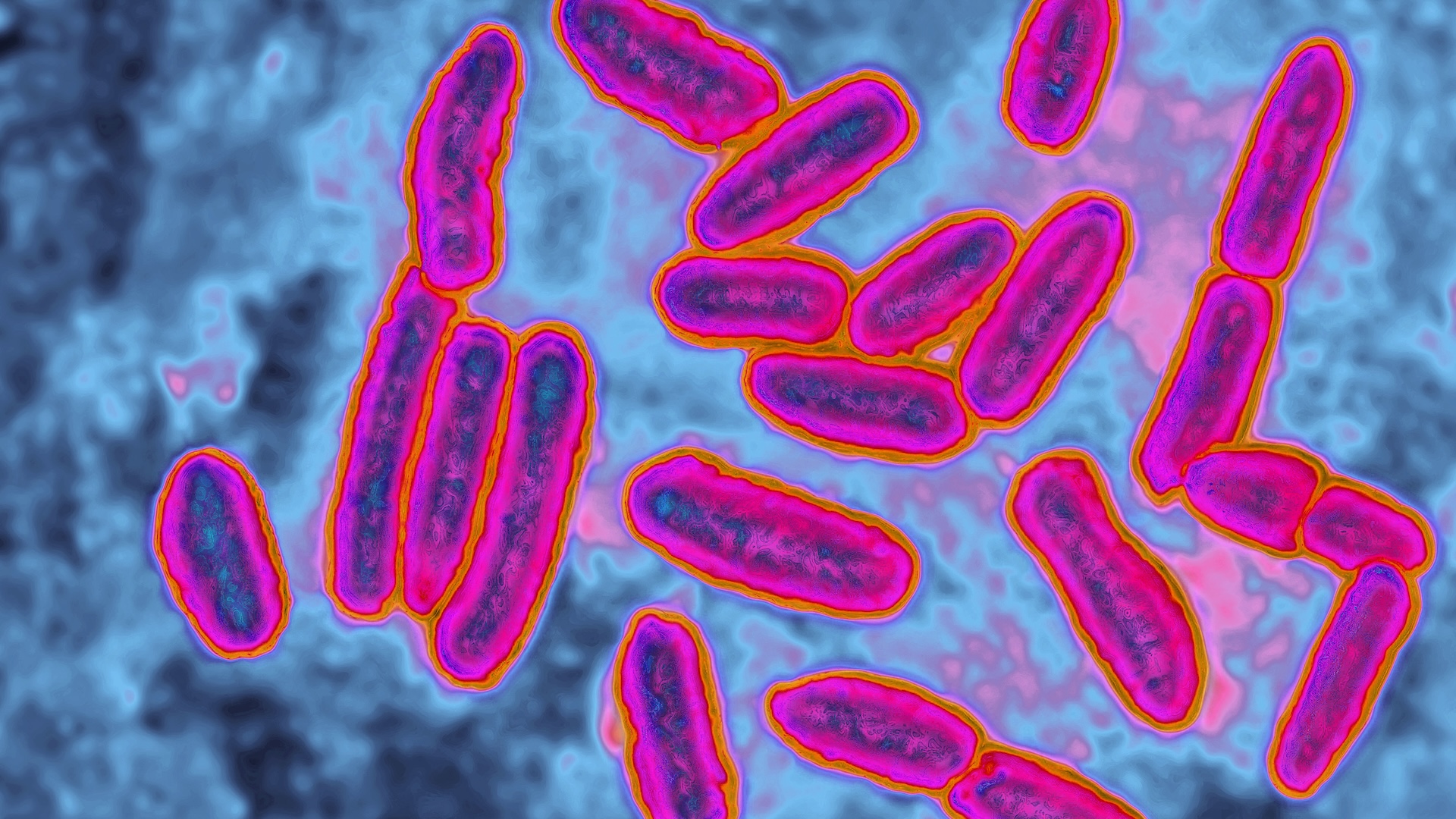

A crisis some call a "silent pandemic" is sweeping the globe. It's grown steadily and stealthily, without drawing as much attention as viral outbreaks that have flared up over the same period. The culprit driving this pandemic: multidrug-resistant bacteria, also known as superbugs.

Superbugs show extensive antibiotic resistance, meaning drugs that would historically cure people of the infections stop working. Bacteria develop this resistance over time as they evolve, and they can easily share that resistance with other microbes, thus compounding the issue.

Scientists are working to develop alternatives to antibiotics, as well as employing strategies to make existing drugs work better. Live Science has been documenting their efforts, as well as the emergence and spread of new superbugs, over the past year. Here are 10 of our most important and interesting superbug stories from 2024.

Related: 10 of the deadliest superbugs that scientists are worried about

Killing CRAB

A newfound antibiotic can kill carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii, or CRAB, a superbug that's resistant to most existing drugs. The drug represents a novel class of antibiotic, and it slays bacteria by messing with the machinery they need to build their outer membranes. The mechanism is highly selective, meaning the drug works only on A. baumannii. This narrow target makes the drug less likely to pressure other bacterial species into developing resistance, scientists reported.

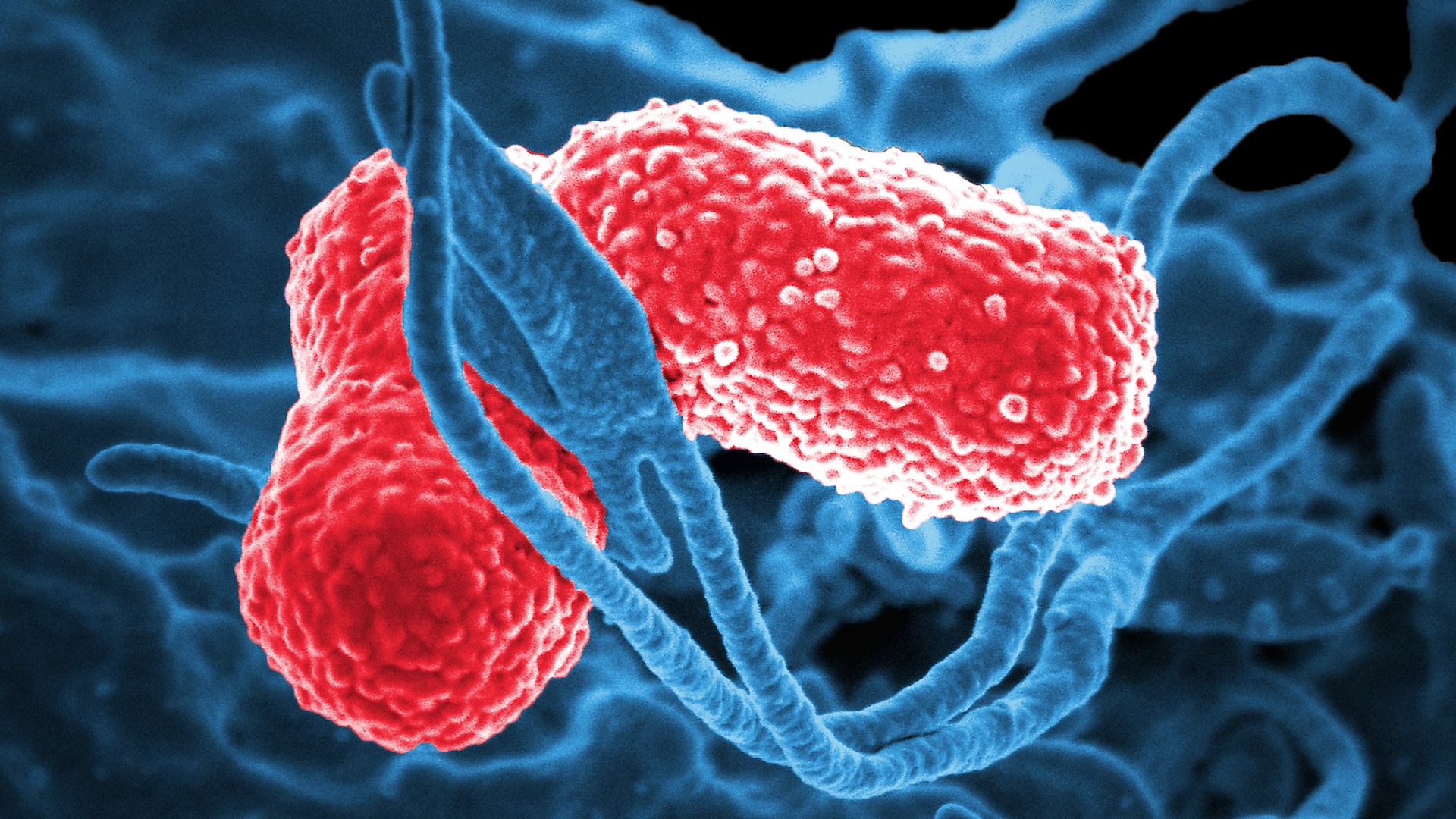

"Hypervirulent" superbug is spreading

New strains of a superbug called hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae (hvKp) have been detected in 16 countries, including the United States. Classic versions of the microbe were already a big problem, especially among people with weakened immune systems in health care settings. But now, hvKp is becoming more widespread — it can cause severe, fast-progressing infections, even in people with robust immune systems.

Lingering bugs in the body

A study found that two concerning superbugs — namely, various antibiotic-resistant strains of K. pneumoniae and E. coli — can linger in the human body for up to five and nine years, respectively. This puts the carriers of these bacteria at risk of recurrent infection and of exposing other people to the same microbes. In the meantime, the superbugs also have a chance to share their antibiotic-resistant genes with other bacteria.

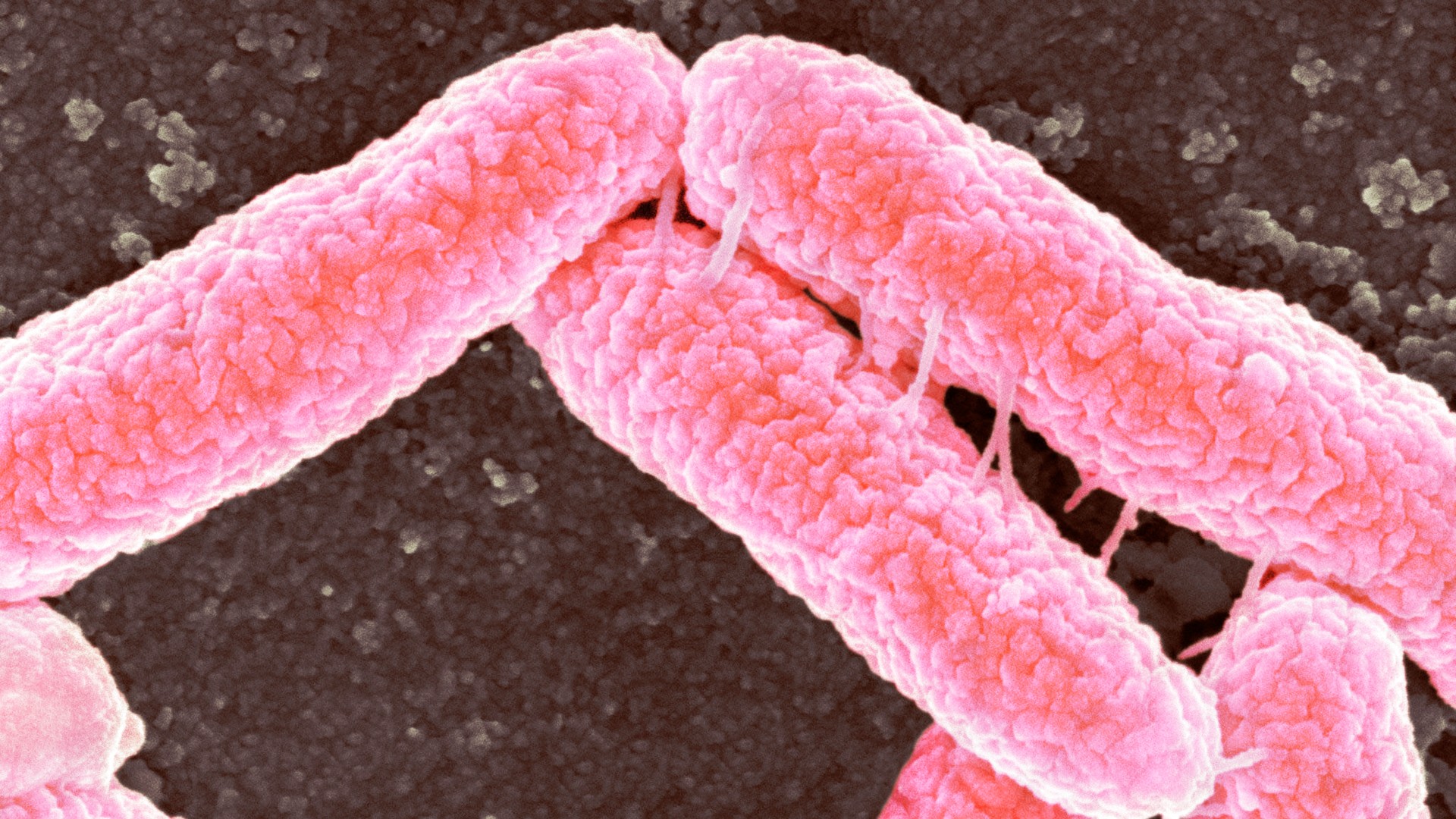

C. diff evolution

The superbug Clostridioides difficile (formerly called Clostridium difficile) — or C. diff, for short — can quickly evolve resistance to one of the main drugs used to treat it. However, this evolution comes at a cost, scientists found. Once the microbe becomes resistant, it seems to grow less efficiently. Understanding the nuances of how C. diff adapts to different antibiotics could help scientists develop new treatments that are harder for the bug to resist.

Kryptonite for superbugs?

Could there be a way to transform superbugs back into average microbes that are vulnerable to antibiotics? Scientists are exploring strategies to do just that, evolutionary biologist Tiffany Taylor explained. For example, some researchers hope to use phages — viruses that attack bacteria — to deliver genes into superbugs that reverse their antibiotic resistance. Other labs are finding strategies to stop bacteria from forming tough-to-treat "biofilms," or from making certain proteins. Together, these efforts are intended to keep our current antibiotics working as well as they can, for as long as possible.

"Phage whisperer"

As the problem of antibiotic resistance continues to swell, some scientists are hunting for alternative treatments for bacterial infections. One of these treatments, called phage therapy, actually existed before the discovery of antibiotics but fell to the wayside once the essential drugs rose to prominence. In this excerpt of her latest book, science journalist Lina Zeldovich highlights some early pioneers of phage therapy, which uses viruses to fight bacteria.

Related: Superbugs are on the rise. How can we prevent antibiotics from becoming obsolete?

How quickly can resistance emerge?

How quickly can a given bacterium evolve resistance to antibiotics? Notably, evolution rates vary among bacterial species, along with other factors that shape their inner workings. But generally, bacteria can pick up the mutations needed to become resistant instantaneously or within a few days. In an infected person, a whole population of bacterial cells can gain resistance very efficiently because once one cell has a resistance gene, it can share that gene with its neighbors.

Deep-sea antibiotics

The next generation of antibiotics may be lurking in the deep sea, scientists reported. Researchers found that Arctic Ocean microbes called Actinobacteria make unique antibiotic compounds. These compounds showed promise in lab-dish experiments with "enteropathogenic" E. coli, which causes intestinal infections. But it will be some time before we know if these compounds will be clinically useful.

Unpacking "heteroresistance"

Some scientists are investigating a unique form of antibiotic resistance called "heteroresistance." Heteroresistant microbes can initially be vulnerable to antibiotics, but when exposed to a certain dose, they suddenly "turn on" their resistance. These bacteria may thwart a patient's treatment, requiring them to switch antibiotics or stay in the hospital longer. And we don't yet have good ways to test for the germs ahead of time, microbiologist Karin Hjort told Live Science.

New fungal infection in China

Scientists in China reported the identification of a new fungal infection that had never been seen in humans. While bacteria that are resistant to antibiotics are a growing threat, so too are fungi that are impervious to antifungal drugs. In this case, the fungus — Rhodosporidiobolus fluvialis — showed resistance to several first-line antifungals when grown in the lab at temperatures similar to those of the human body. The study's findings suggested that, as climate change progresses, R. fluvialis and similar yeasts could evolve to gain more resistance.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.

Cancer: Facts about the diseases that cause out-of-control cell growth

Diagnostic dilemma: A man had hiccups for 5 days — and a virus may have been to blame